Filmmaker and performance artist Samira Elagoz likes to join his spectators in front of the camera, capturing relationships in an intimacy deprived society. That often leaves the spectator to question the fictionality, performativity, and realness of the work but as Samira has written: “Romance is business and business is romance”

Rumoured to be queer, provocative and emotionally intense, Seek Bromance was a must-see for me. The social media influenced dramaturgy and editing kept me on the edge of my seat for 240 minutes and I was fully immersed in Samira's transition from high femme to transmasculine. Seek Bromance had initiated a personal process of constructing and deconstructing my perspectives on performing and practicing gender, first having to critically examine and then reinvent how I've perceived the “conventional” narrative of being trans. This interview is a sequel to questions I was left with after being introduced to Samira's practice and a prequel to him coming to perform Seek Bromance at the festival SAAL Biennaal in Tallinn in August.

This is something I've been meaning to ask for a while – how do you prefer to be called?

My name is and always was Samira Elagoz. But people often call me Sam. During my three years of being out as trans, many have asked if I will change my name, but the truth is I don't care so much for names. I believe they belong to gravestones. My relationship with “Samira” is complicated though. I hated it my whole youth as I was constantly bullied for being half Egyptian. While I could “pass as Finnish”, my name would always give me away. But later in life I became very proud of it. So, for me, “Samira” is not a marker of being a woman but of my background.

How do you carry the pressure and responsibility of having become the voice for many transmasculine people? Or the voice of sexual violence victims?

I believe one cannot, and should not, represent a “community”. To be expected to be a spokesperson for an entire demographic is unrealistic and unfair. If you are an artist from a minority or oppressed group, you are always being reviewed for what you represent, and whether your performance of representation is adequate. Any consideration of your merit as director, dramaturge, or editor, is entirely secondary, if that. The judgement is always personal, aimed at your appearance or behaviour, rather than how you make your work. White cis men, conversely, have been given this sense of neutrality, where they have the freedom to represent others, and tell stories they’ve merely observed. In addition, marginalised artists are held to a higher level of purity, and have the most to lose by not living up to imagined standards.

Could you define the transmasculine gaze in relation to the male/female gaze?

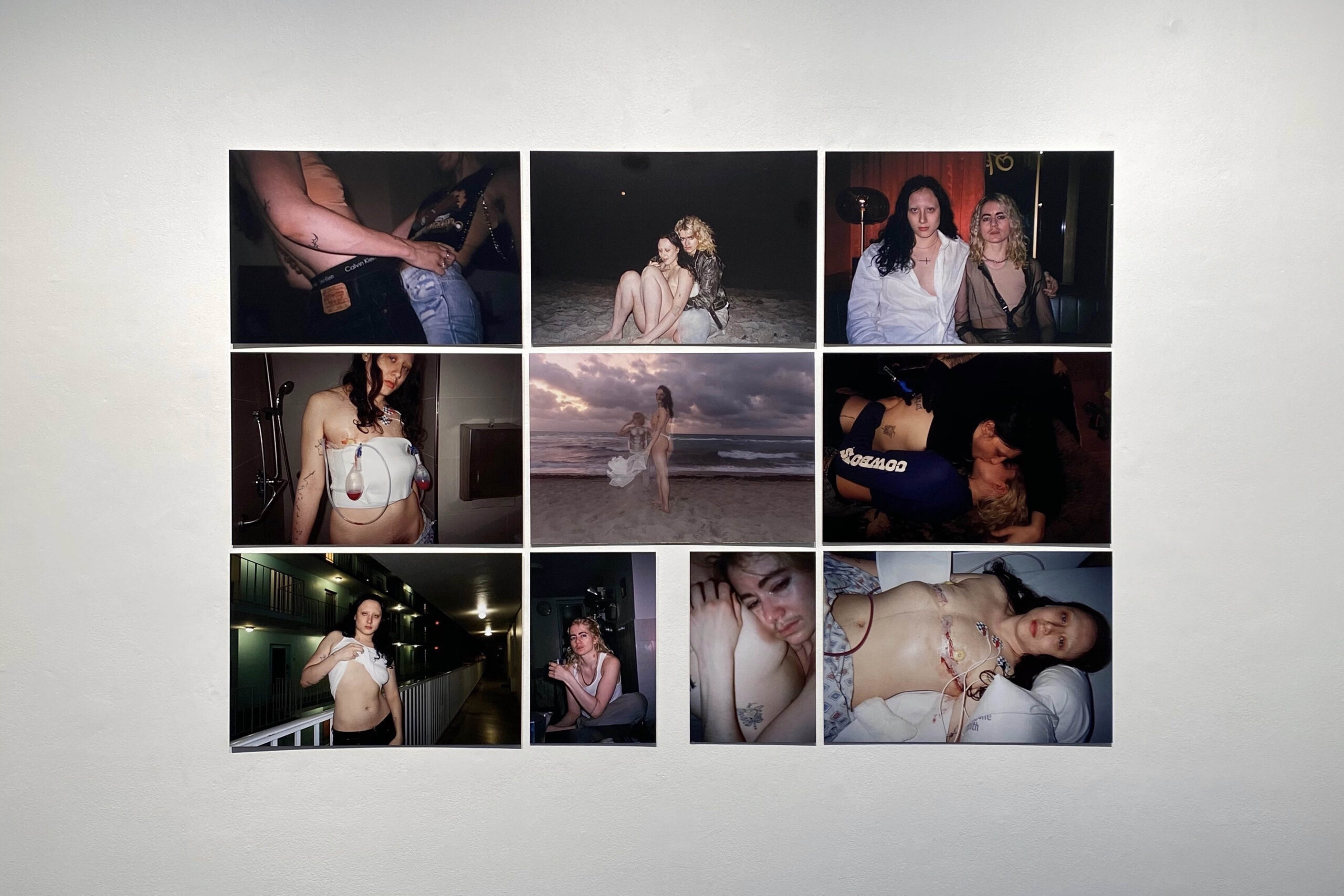

A defining moment in my career was in 2015, when I went to a retrospective exhibition of a famous male photographer. I remember thinking what a shame that this man met all these women throughout his life, and managed to portray them all in the same way. The thing about the male gaze is that at its core, it is boring – men projecting lascivious fantasies onto women. I decided then that when I have my retrospective one day, people will be able to see the life I experienced with my subjects/collaborators.

I’ve been filming strangers for ten years now, and I never had the intent of ascribing them to a specific role. My subjects could show themselves to me as they wanted to be seen. I gave them the freedom to use the camera, to turn it around on me. But to be frank, I’m not so invested in the gender of gaze anymore. A curious gaze should not be tied to the maker's gender, but the way they choose to make work. In film, you could say it is in character development. How complex, unpredictable, or realistic you make your characters. Storytelling is universal, and the male perspective can no longer be considered the default one.

What is the power you hold as the initiator of a documentary artwork? Is it even power? Responsibility? A request to co-parent an unborn artwork?

I always knew I didn't want to make traditional documentaries. I think it’s rather cowardly to be just behind the camera, to not put yourself on the line. My works are not a collection of portraits, but interactions between me and my subjects or collaborators. When I step into my camera’s frame, and offer the people I film a chance to use the camera, I try to create a dynamic in which the camera’s gaze is in constant dialogue. As for my collaborations, it’s important to me that the filming process is influenced by both of us. I've offered them the chance to be part of the editing, and it’s crucial that we get paid the same amount. That being said, anytime you represent someone else there is an inevitable power dynamic. I understand the vulnerability of being shown through someone else’s POV, and the courage it takes to be perceived. And even though I've thought a lot about these dynamics and created methods to offset and equalise them, they will be present.

My newest collaboration You Can’t Get What You Want But You Can Get Me with my partner Z Walsh was my first experience working with someone who was as keen to film me as I was him. I finally found someone with whom there wasn’t much of a power dynamic because we both shared the same need and curiosity to document our relationship since the moment we met.

How does the presence of a camera – the potential of a foreign gaze, an unknown number of strangers in the space with you – influence intimate situations?

The process of building a relationship, romantic or not, in front of a camera is a vulnerable and unpredictable experience for both parties. Meeting in the presence of a camera heightens a lot of the interactions. Romance is more romantic, excitement more exciting. Similarly, awkwardness can easily become tension.

Therapist Esther Perel, who publicly podcasts some of her sessions, says that couples therapy is the best theatre in town. In any situation where real intimacy is portrayed publicly, be it an artwork or reality TV, you open yourself up to be judged for the most private parts of your life. I personally believe there is something noble about placing your life, issues, insecurities and epiphanies on display, to trust your experience is human, and shared, and of value. We should admire people who dare to expose themselves like that.

Assuming there is the freedom to not have to entirely perform yourself – how much effort do you put into staying yourself in a situation where the camera is facing you?

I recently read a quote from Ingmar Bergman: “I could always live in my art but never in my life.” Autism runs in my family, and while I’ve never been formally diagnosed and have no intention of self-diagnosing, social interactions have always felt like a struggle to me. I’ve often felt like an alien who cannot socialise, and this has led me to perform socially in my real life, more than in my art. I've needed to mask and practise social choreography. Being in front of and behind the camera are some of the only places where I feel like I can be genuine, where I feel truly alive. And while people may not regard that as being my authentic self, to me, it is.

Working between documentary and performance I often face questions about authenticity. The main question remains: how performative is this documentary? An unanswerable question, because even if I would try to act like myself, the audience could never be sure to what extent that “self” is being performed, nor what my motives are.

I do feel the art world is often afraid of being incorrect or too triggering. Subconsciously, I tend to expect artists dealing with contemporary topics to constantly question right and wrong, lead the way, and never suggest that being triggered and cared for may not be opposites. Why is it important for the viewer to be triggered?

I think the position of spectatorship is by default triggering. To be left only to witness, without being able to act in the moment. The passiveness of spectatorship can be quite paralysing regardless of the topic of the work. I recently read an interview with Nick Cave who said it’s the most problematic individuals that produce the best art. Although I cannot fully subscribe to that idea, I do think the greatest art can’t be made by moralists. I am convinced that the most powerful works arise from a place of nuanced understanding, and acceptance of complexity. Artists shouldn’t strive to be role models.

How do you direct the way the artwork triggers, and then “hold space” for the triggered?

I do put a lot of thought into how I construct dramaturgy, build tension and relieve it. I think the care happens there. However, I try to make my works without moralising, or giving readymade conclusions. I want the mic to turn towards the audience in the end. They should be left with a desire to articulate for themselves.