A friend of mine once mentioned that she can immediately spot Estonian women in random European airports by their bleached hair. A few years ago, at a friend's birthday party, I met a German theatre director, a man who had been in Estonia for two weeks and was wondering why so many women here bleach their hair. At first, these comments left me somewhat confused – after all, these were very subjective observations. But they did stick with me, as I, too, have had blonde highlights in my hair for a considerable period of my life. The fear of the potato peel shade – as the natural dark blonde/light brown shade is disparagingly called in Estonia – is really notable. It is considered a thoroughly unremarkable shade that makes a person look plain and bland. So, women go to salons regularly to colour their hair for a more dynamic and youthful look. The hair stylists I asked about this admitted that bleaching and various techniques, such as ombre, balayage, air touch etc. make up a large part of their daily work.

In 2020, curators Kadi Polli and Linda Kaljundi commissioned a new artwork from me for the new permanent exposition at Kumu Art Museum that would comment on the new ideal of female beauty that emerged in Estonia in the 1930s. To an extent, I was aware of how women were represented in Estonia in the 1930s and 1940s, during the so-called silent era, a period of nationalist-conservative dictatorship. A few years prior, I had worked with the collections of the Võru Museum

Beautiful hair – the pride of women!Slogan for Veronika Blondol Shampoo in the magazine Maret, June 1937

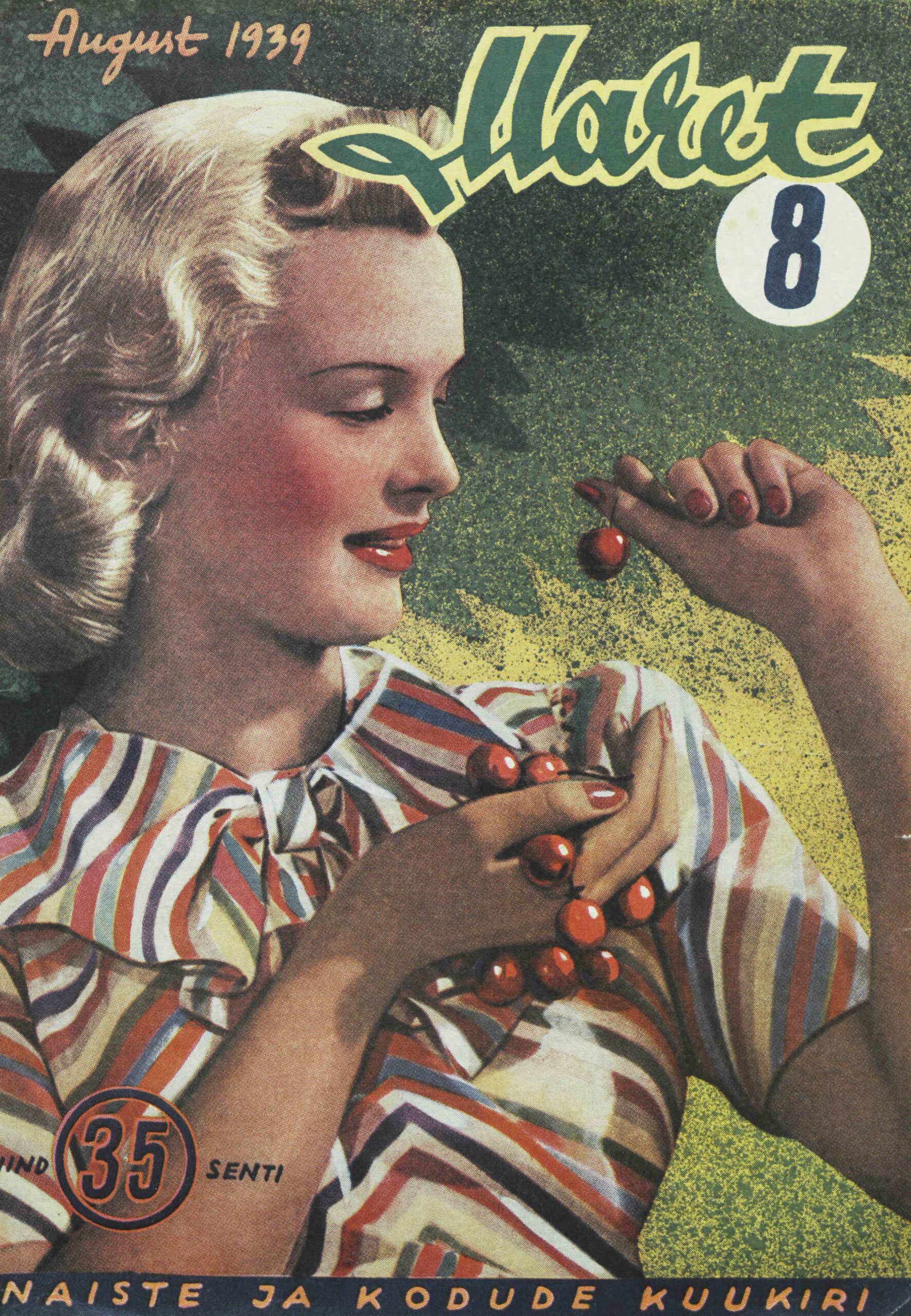

The term "hair industry" came into use in Estonia in the 1920s and in the following decade hair salons began offering bleaching alongside services such as finger waves and permanent waves. Looking at the portrait photographs of socialites and actresses of the time, such as Betty Kuuskemaa or Signe (Sisy) Pinna, we can see that the women with already rather fair hair became platinum blonde in the 1930s. When it comes to this trend, the influence of Hollywood cannot be underestimated. One of the most famous film divas of the time, Jean Harlow was often mentioned in connection with her platinum blonde look.

While in the 1920s, Estonian newspapers were covering rather cosmopolitan subject matter – fashion and entertainment news from Paris and Hollywood, as well as the role of women in politics – in the 1930s, an increasing number of articles, concerning the decreasing population and the weakening of marriage as an institution were published. After the bloodless coup of 1934 in Estonia

In the collections of the Art Museum of Estonia, there is at least one portrait from each decade by Laikmaa since he started his artistic practice at the beginning of the 20th century, depicting a woman or a girl in national dress against a dark background. He often portrayed women from Vigala, his birthplace, but also those from other parishes in the western part of Estonia. In summer 1928, just before the Estonian Song Festival

Systems of visual calibration

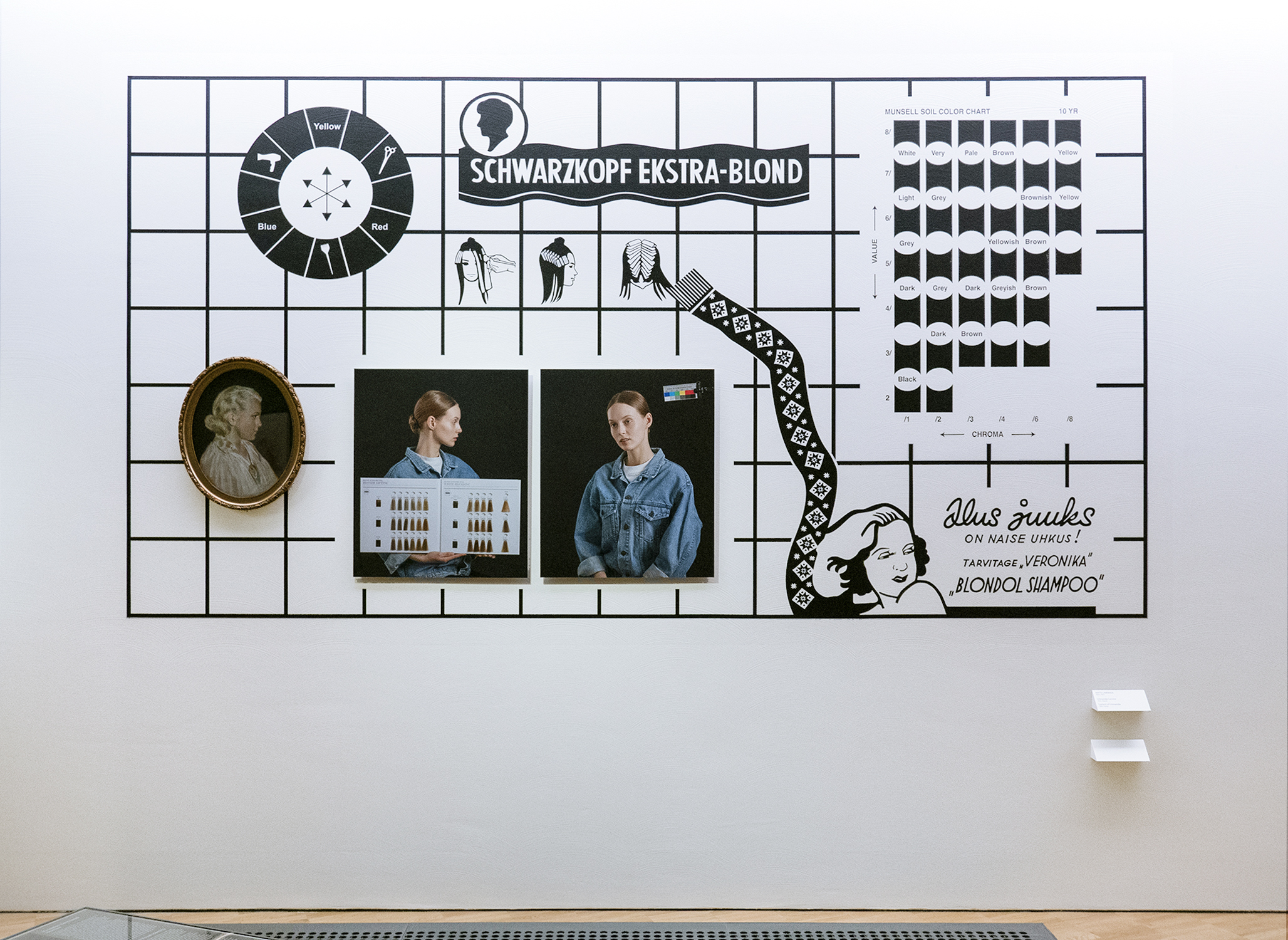

This process led me to create a wall installation combining photography and various print elements, as this seemed the most appropriate way to communicate the complex net of references around the issue. The central position in the installation is given to a colourful twin portrait depicting a young woman in profile (similar to Linnamäe Lemmi) and three-quarter profile (Portrait of a Girl). A similar portrayal was used in the 19th century in anthropological photographs but also in photographs made within the court system. In the history of Estonian photography, the best known examples are probably the ethnographic portraits of Estonian peasants taken by Charles Borchardt that received a silver medal at the 1867 Pan-Russian ethnography competition of the Association of Natural Scientists of the Moscow Imperial University.

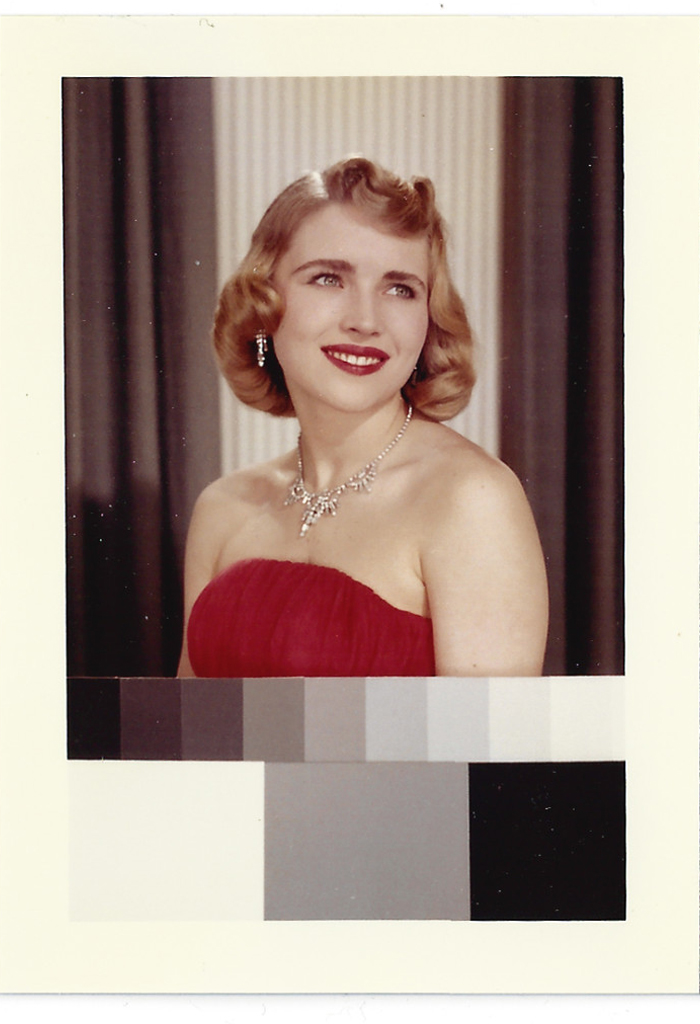

Just like Laikmaa before me, I wanted to create a portrait of a contemporary young woman as well. I aimed for the model to be around the same age as Lemmi in Laikmaa's portrait and with hair that had not been coloured. On the one hand, this was meant as a reference to the potato peel shade I mentioned earlier, but on the other, it also allowed me to juxtapose her natural hair colour to the hair colour sample chart the model is holding in the photograph. With the help of an agency, I found Merilin Perli, a professional model, whose profile is amazingly similar to Linnamäe Lemmi's. As the curators were open minded, we were able to integrate Laikmaa's pastel and my wall installation so that the portraits of women from very different eras could be viewed side by side. In the three-quarter portrait, the Kodak colour control patches and grey scale have been placed next to the model's face. Formally, this photograph was inspired by the so-called Shirley Card, used to test exposure and colours both in film and television.

Male gaze and white gaze

In the Western visual culture, where men have traditionally been artists and women have been those they depict, most images are created for men's viewing pleasure. For example, film theorist Laura Mulvey uses psychoanalytical theories to look at depictions of women in mainstream cinema, including Alfred Hitchcock's films, featuring platinum blonde women: "The power to subject another person to the will sadistically or to the gaze voyeuristically is turned on to the women as the object of both."

The myth of the blonde blue-eyed Estonian woman can be seen as an expression of the myth of whiteness, yet genetics have probably also contributed. Many less pigmented Northern Europeans, including Estonians, have extremely light hair in their childhood. However, like the hair stylist Kaja Seppel told me in an interview, as the cycle of hair growth is 5–7 years, people's hair pigment changes significantly over the course of a person's life – some people's hair gets darker, some develop curls etc. The self-image they develop in childhood and the desire to hold on to it might be one of the contributing factors why women in Estonia keep bleaching their hair for the rest of their life. Like all beauty ideals, the archetype of the blonde Estonian woman persists through the finer forms of visual representation that often go unacknowledged.