According to a recent wage survey, the average monthly income of art practitioners in Estonia is 600 euros

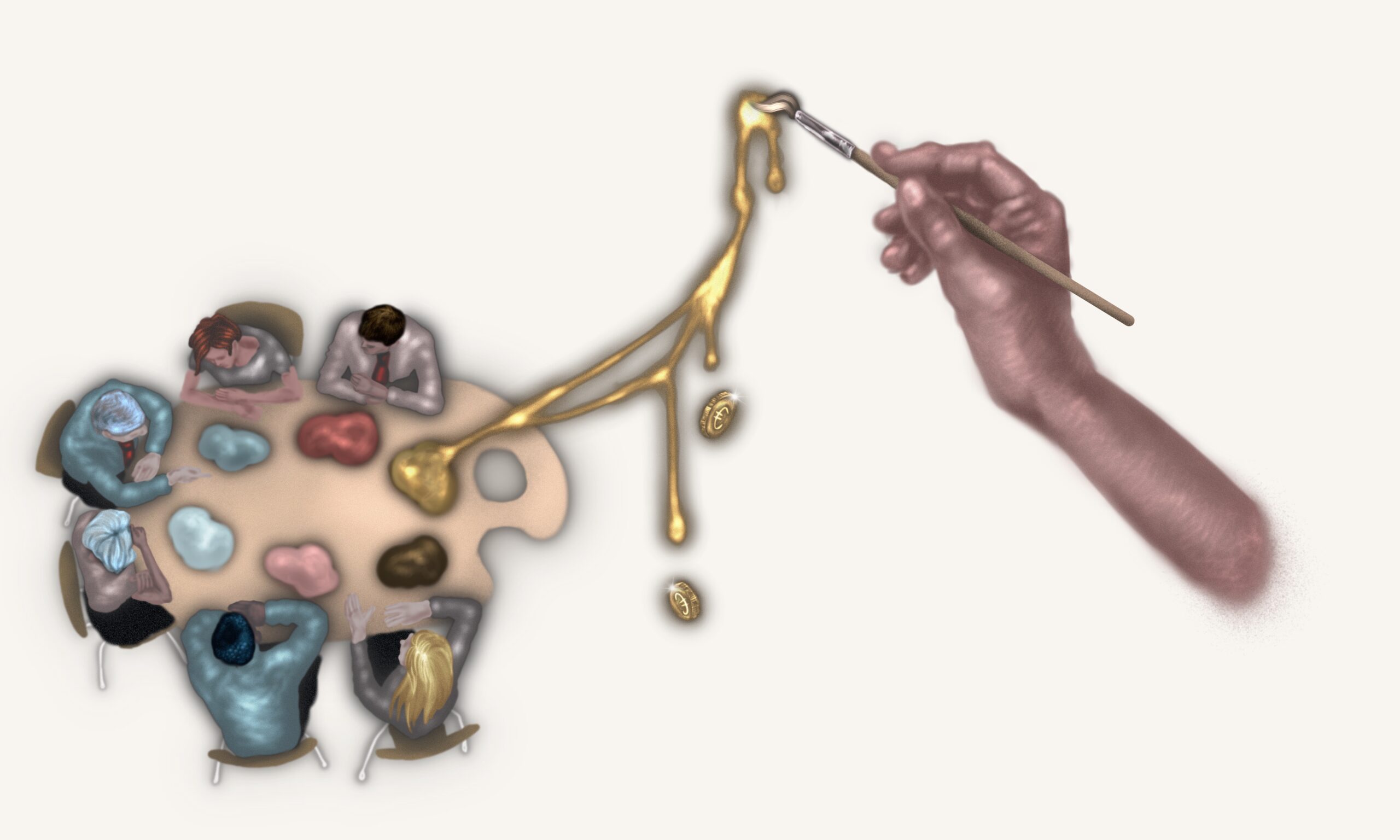

The proposal focuses on exhibition making, which is a core activity in the art sector. Participating in exhibitions should generate substantial income for art workers; however, this is currently not the case. Even the most well-funded exhibition spaces pay artist fees that are barely in sync with the national minimum wage. The remuneration of artists is usually lower than the pay of installation technicians, graphic designers, project managers, curators or exhibition designers. In many cases, artists are funding the exhibitions from their own pocket, either through unpaid labour or finances channelled into production costs. There is no consensus that making art is work that should be recognised and remunerated as such.

Why are wages important?

The fair pay proposal suggests a three-tiered model, taking into account the budget limits of different exhibition spaces. The highest fee rate is linked to the minimum wage of cultural workers (currently 1,600 euros per month), which is a wage tariff applied to the permanent employees of some state funded institutions. The lowest fee rate is linked to the national minimum wage (725 euros per month or 4.30 per hour), a standard which also has limited reach. The minimum wage is legally binding for all conventional employment contracts; however, in the art sector incomes are usually lower because the law does not apply to temporary work contracts. There is no consensus in the art field about complying with the minimal standards voluntarily.

For freelance art workers, earning the minimum monthly wage is crucial because access to health insurance, unemployment protection and future retirement pension depends on it. The minimum wage has been rising every year, whereas incomes in the art sector remain stagnant. From the perspective of art workers, chasing the minimum wage is a sport that demands a truly athletic performance. Another problem is that not all income is paid in the form of wages – grants, licence fees and art sales are not subject to labour taxes and therefore do not grant access to the social security system. A recent study showed that 49% of freelance cultural workers in Estonia do not have stable access to health insurance

Why is tracking time necessary?

Before developing our proposal, we researched fair pay standards in other countries and presented three examples for public discussion: the MU Agreement in Sweden, the recommendations developed by Carfac in Canada, and W.A.G.E. in New York

Negotiating on the basis of workload is not a common practice in the art sector. The fees are usually dictated by institutions who approach freelance art workers once their budget is already fixed. These budgets do not realistically reflect the time needed to carry out the work.

In group conversations with art practitioners, we tried to estimate the average time needed to produce art works and exhibitions. For example, artists estimated that the preparation of a solo exhibition requires 6–9 months of full-time work, although the preparation period itself is usually longer because the intensity of work varies over time. The workload also depends on external factors such as the size of the exhibition space and the availability of institutional support staff. Based on the group conversations, we developed negotiation guidelines with negotiation guidelines that can be used to discuss the division of labour between the artist and the institution. This worksheet also highlights activities that are often overseen when agreements about workload are made, such as attending meetings and writing emails, participating in public programmes or giving interviews to the press. However, creative work cannot always be planned and measured precisely. Some concepts take time to mature, while others are born in the moment; some ideas are easy to realise, others require long experimentation with materials, techniques or skills. The negotiations about workload and fair pay should not only focus on administrative tasks that can be easily measured, but it is important to consider that the creative process also takes time.

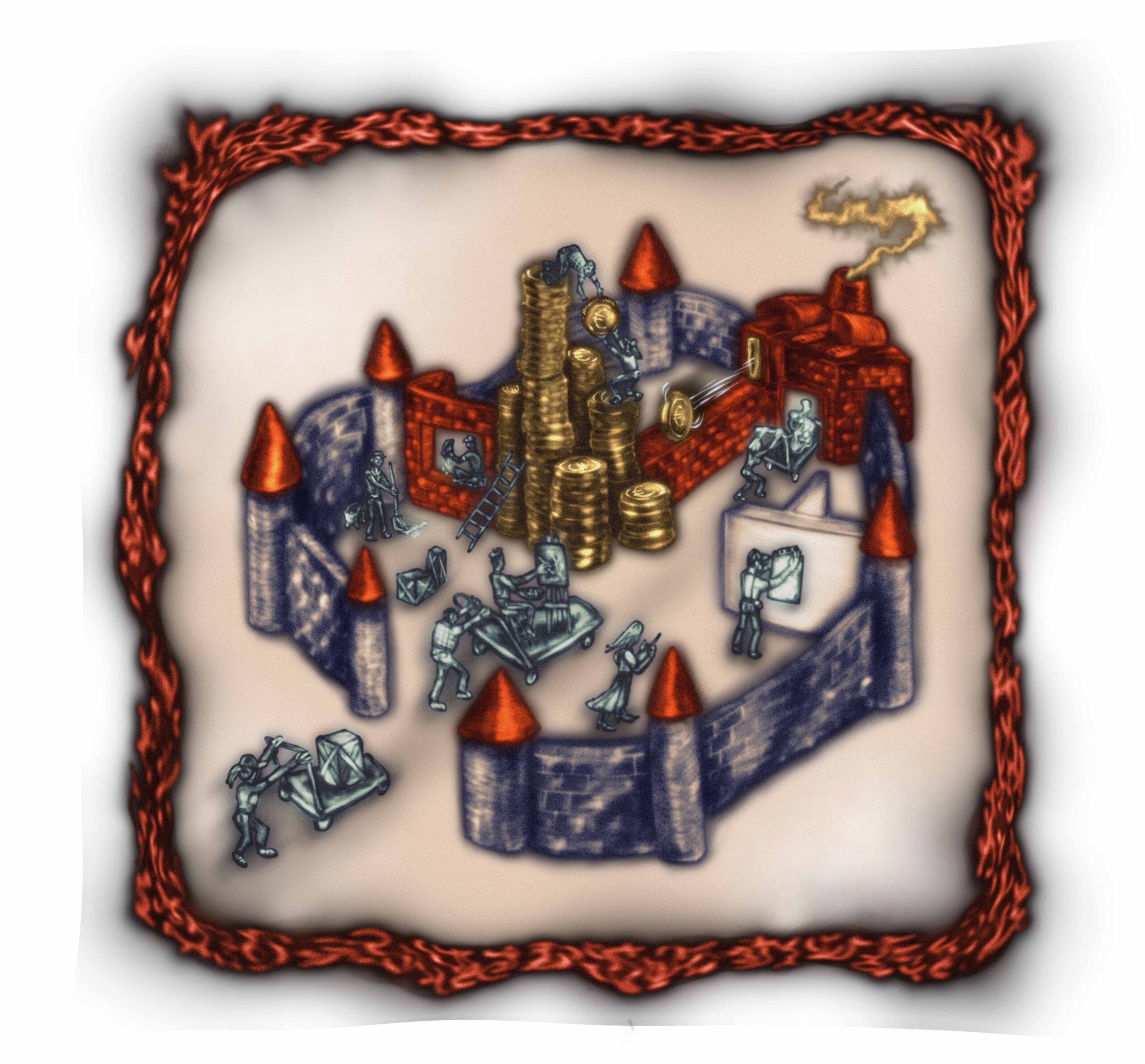

Why is collective organising essential?

Not much has changed during the one and a half years since the fair pay proposal was published. Two institutions have partially modelled their fee tariffs according to the proposal. Tallinn Art Hall linked their artist fees with the minimum wage for cultural workers; however, the workload calculations are unrealistic – for the preparation of a large solo exhibition artists receive the payment of only three months – and thus the artist fees are actually closer to the national minimum wage which is roughly two times lower. The magazine A Shade Colder follows the proposed fee schedule for writers; however, the rates have not been adjusted to factor in the high inflation and the rise in the minimum wage tariffs in 2023. Some institutions have made adjustments that do not require financial means, such as improving legal awareness and adjusting communication protocols. It is commonly agreed that establishing new labour standards requires additional funding for art and culture. This aim can be achieved only through collective pressure.

In the past decade, the visual art sector in Estonia has gone through two different cycles of debate addressing un(der)paid labour. The first cycle took place in 2009–2011 as a collective organising process and coincided with an international wave of self-organised movements of art workers mobilised in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The ongoing cycle (from 2019 onwards) has been led by individual experts, advocacy organisations and the ministry of culture. This shift in the forms of organising mirrors certain general patterns characteristic to labour struggles in Estonia. In the trade union movement, the preference is for a top-down service model in which the trade union offers counselling, support and services for members rather than empowering their active participation

According to a recent survey, only 4% of art workers are organised in trade unions, while 68% are members of creative associations which function as the most important advocacy organisations in the cultural sector