At first glance, Jaanus Samma's works resemble souvenirs with ethnographic motifs and some even evoke pure nationalist kitsch. This is, of course, a treacherous trap, set for the unsuspecting viewer. The artist seems to approach folk heritage and the past in the most conservative way possible; however, on closer inspection it becomes evident that the national ornament has, in fact, been stripped of pathos and solemnity – under the layer of ethnographic beauty bubbles an explosive mix of provocative questions. Jaanus Samma's works have been discussed as homonationalist acts

Personal mythology

At his recent exhibition (in collaboration with Carlos Motta) Otherness, Desire, the Vernacular

Noble and dirty patterns

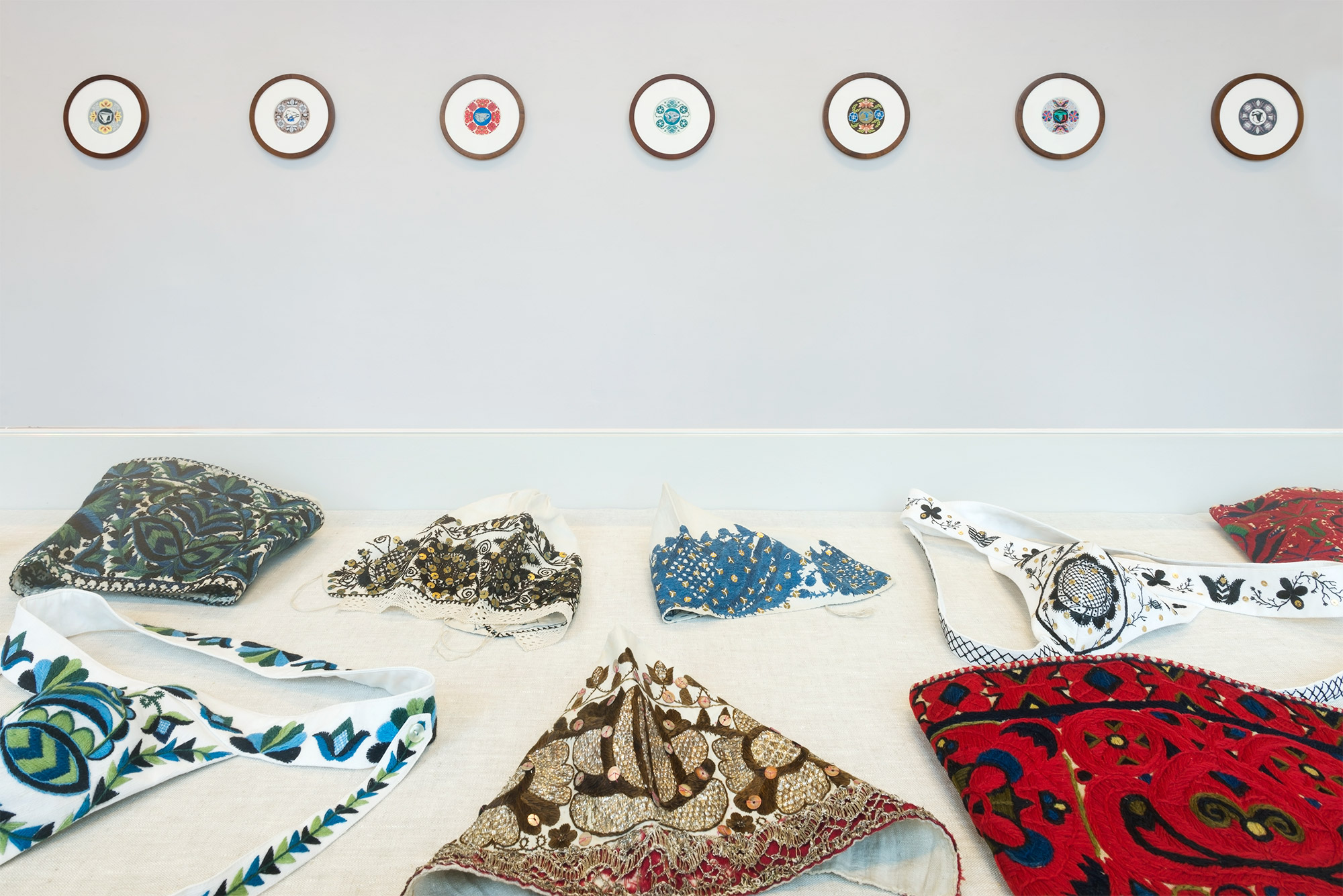

At the exhibition Pattern, Samma exhibited 19th century coifs (tanu), on loan from the Estonian National Museum, side by side with drawings and embroidery inspired by the headwear. With these works, Samma continues exploring the hidden cruising culture and fetishes in gay communities, also present in his previous projects. Here, the focus is on men's underwear and jockstraps, provocatively decorated with perfectly executed national floral embroidery. The coif signalled the wearer to be a married woman – Estonian peasant women had to wear these daily as a symbol of that status. Furthermore, as part of a wedding ritual, the freshly married woman was slapped on the head or in the face with the coif and told, ‘…forget sleep and remember your husband!’ The beautifully embroidered coif was a sign that the woman was no longer single, and moreover, it was also meant to remind her of her position within that union at all times.

These embroidered patterns, created by illiterate women are the only letters we have of them. We could say that these patterns are essentially and specifically 'Estonian', but obviously, international fashions have not left the work of these women untouched either. These baroque floral patterns, originally from north Estonia, acquired strong nationalist associations only later on, at the beginning of the 20th century, when the Estonian National Museum acquired the most aesthetic and 'authentically Estonian' examples of garments for their collections and these became known as folk dress. The founders of the museum hoped that based on the items they collected, local artists and applied artists could develop an idiosyncratic Estonian national style. With a layover as a tool for the Estonian authoritarian regime of the 1930s, these patterns also made it into art of the Stalinist era and are still represented in conservative nationalist applied art in full glory today.

Looking from a distance, Jaanus Samma's dignified flower motif wreath drawings would fit well in both the castle of Konstantin Päts, the authoritarian president of Estonia, as well as a Stalinist palace of culture; however, taking a closer look, we see that this is not sincere national kitsch after all. What meanings emerge when patterns stolen from the coifs of married women come to decorate jockstraps as part of the hidden heritage of gay culture? Is this a homonationalist incursion into the heritage of Estonian national ethnography or the grief of the queer subject recently declared incapable of marriage