Encountering beauty evokes a desire to experience it first hand, to be near it, to have it rub off on you but also to own it – and this is exactly what the fascination with and the global trade in orchids has been driven by. This industry operates on such a massive scale that it seems almost mundane, banalising the destruction it leaves behind – it has a long history ranging from treasure hunting to mass market availability.

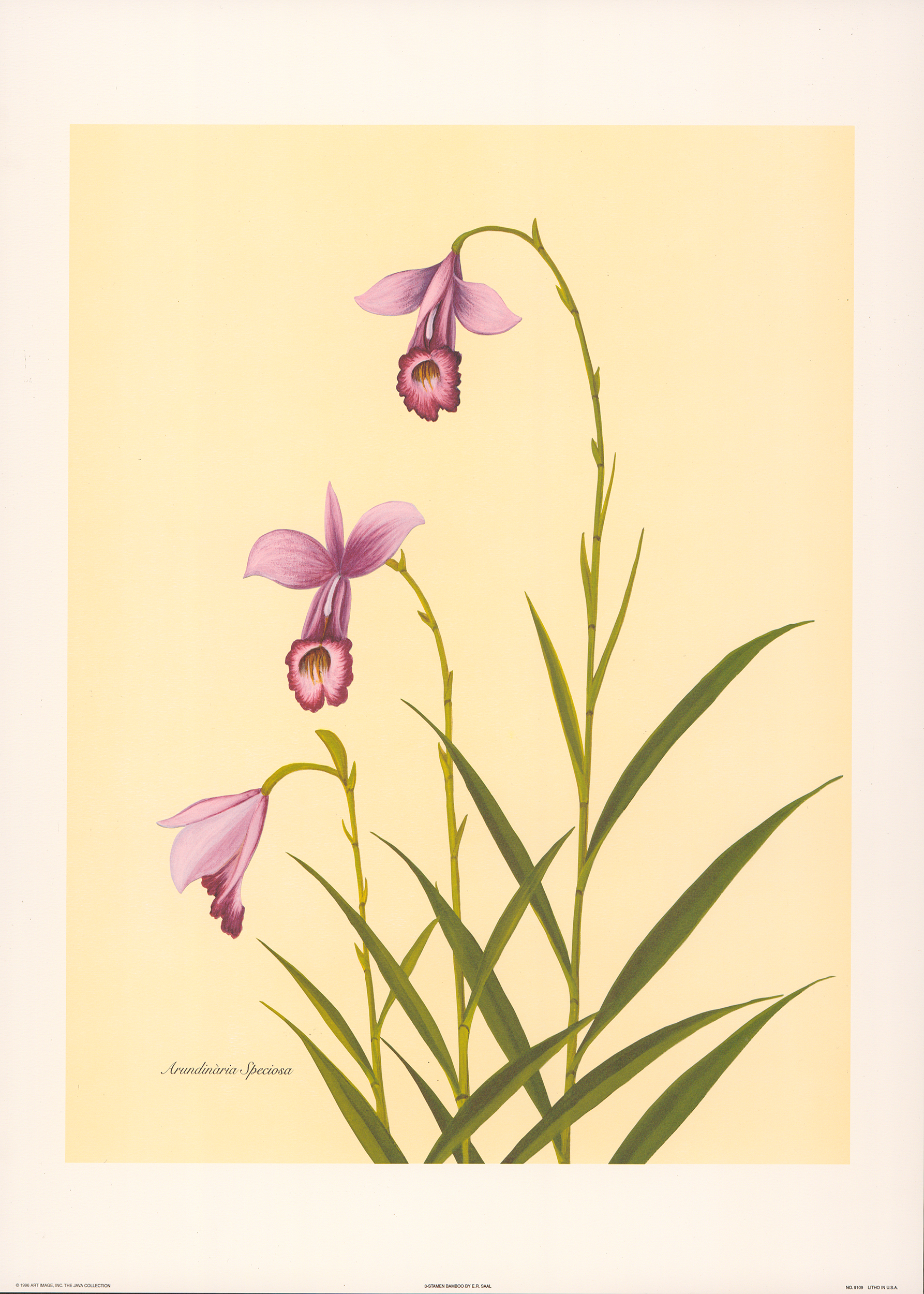

Taking this as a starting point, artists Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi together with curator Corina Apostol conceived Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance, tracing a story of global interconnections between art, colonialism, botany and dualities, to be presented at the Estonian pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale. At the heart of the exhibition is the story of a relatively unknown artist Emilie Rosalie Saal (1871–1954), whose work as a botanical artist was closely tied to her life in Indonesia, where she relocated when her husband was employed by the Dutch colonial authorities as a cartographer.

Photo: Dénes Farkas/ CCA Estonia

What was it that inspired you about Emilie Saal’s story initially? Has your perception and perhaps attitude towards her work changed during the two years you have worked on Orchidelirium?

Corina Apostol: The project started with an exhibition I began developing with Kristina on histories of colonialism, and the role of Estonians in it, and to provide an alternative view to the understanding that Estonians have been, above all, the colonised and not the colonisers. On the one hand, we wanted to unearth and highlight Emilie Saal’s story and to focus on female subjectivity and the universe she lived and worked in. But as the project developed, I also wanted to point to her role in the colonial project, as her botanical art was also a tool of the empire. So, the project is also looking at the consequences of colonialism in the present.

Kristina Norman: When we were conceiving the project, we were absolutely sure that one part of my Orchidelirium film trilogy would focus on the contemporary workings of neo-colonial extractivism in Indonesia. Figuratively, our aim was to try and trace the legacy and ecological footprints that our protagonist and her fascination with tropical orchids left in Indonesia. But due to Covid-related travel restrictions our planned on-site collaboration with Indonesian creators and communities couldn't happen. I ended up making a film that follows peat that is being extracted on an unprecedented industrial scale from the Estonian bogs for Phalaenopsis nurseries in the Netherlands that use this natural material as a substrate for growing orchids. The natural habitat of Phalaenopsis overlaps with the former Dutch colonies in Indonesia and now these displaced tropical organisms, with their roots squeezed together with Nordic peat into plastic pots, travel back to Estonia where local consumers have no clue that by buying an orchid they greatly contribute to the decline of local biodiversity as well as the quality and accessibility of drinking water.

To me, one of the central questions in the project is that of privilege and its contingent nature – it may increase or decrease as a person moves from context to context. However, there are certain aspects like race, gender and class, that determine the extent to which this is possible. Although not born into wealth, Saal’s whiteness allowed her to gain access to a world of privilege and attain a position in Dutch colonial society. As evident in the novels of her husband, the Saals, coming from a class of peasants and servants to the Baltic German nobility in Estonia, were also sympathetic towards the colonised people of Indonesia. Yet, there are gaps between sympathy, identification and accountability.

CA: We were fascinated by the question of what happens when a person from a humble background, a place that was not even a country at the time (Estonia became independent in 1918 – Ed.) goes to Indonesia and becomes a member of the elite in the Dutch society. We do not know Emilie’s exact thoughts, as we do not have her writings anymore, but she definitely inhabited a position of privilege. But we do have the writings of her husband Andres, who although working for the Dutch, criticised them as well. He saw similarities in the Estonian and Indonesian struggle for independence, for self-determination; and through writing, he introduced Estonians to Indonesian society and culture. The Saals probably saw themselves as more enlightened than the local Dutch elite, yet they were part of the colonial system.

Bita Razavi: Privilege for sure is contingent but also relative. Reading Saal’s biographies, the first things that attracted my attention were the notions of class, access and privilege, which inevitably became the focal point of my work. We often think of class as something that is assigned to people – each person is born with a set of privileges. Being from a third world country (Razavi was born in Iran – Ed.), I have to confess that’s very true. But how much is it possible to tackle these assigned privileges and how much choice is involved? The story of the Saals seem to be so much about the choices they made, while they were no doubt also aware of the privilege that being European bestowed on them. They improved their social class and climbed the colonial hierarchy by moving to Indonesia and choosing to work for the Dutch East Indies. Such choices weren’t equally available for indigenous Indonesians.

The question of privilege does not only stem from the historical timeline of the project but is also very much present in its contemporary presence. The exhibition takes place in a space of privilege, both in a metaphorical and physical sense, afforded to the Estonian commission temporarily when the Netherlands invited Estonia to the Rietveld pavilion in Giardini. How do you claim a space of privilege that is perhaps not quite yours – would you want to do that and on what terms?

CA: There have not been other projects exploring the connection between the Netherlands, Indonesia and Estonia in this way. On my part, I want to create a connection between the research I’ve gathered as presented at the pavilion and references to the building itself. Even though we did not manage to conduct extensive research in Indonesia due to Covid, we are inviting Eko Supriyanto, an Indonesian artist to make an intervention in the space – he will present a newly commissioned video Anggrek (Orchid) in relation to Kristina’s trilogy and the archival material. Through this, we are also trying to problematise and look at the site itself, to peel away its Modernist simplicity, its whiteness. Bita and Kristina are addressing the architecture of the building more specifically and do so in very different ways.

KN: When imagining our future project and looking at the images of the Rietveld pavilion, I couldn't help but recognise its similarities with Baltic German manors in Estonia but also the luxurious colonial villas in the Saal’s family photographs. The white marble and large glass panels surrounding the main entrance to the pavilion reminded me of manorial verandas, the iconic stages for the performance of social class. I imagined Emilie and Andres growing up in Estonia, seeing the German nobility spending their leisure time on the verandas of their manors while their gaze renders their peasant servants as a natural part of the landscape. Exotic plants and noble ladies painting them might have also been part of such veranda scenes. These could have been the images that Andres and Emilie carried with them to Indonesia, where they found themselves in the position to re-embody them themselves. It really is exciting to consider that Emilie did not associate privilege with mere leisure but with women's artistic aspirations. Surely, these aspirations relied heavily on the invisible labour and came at the expense of the aspirations of Indonesian women…

BR: I view the Giardini and this particular pavilion as a space of privilege and look critically at the relationship between national presentations and global power imbalances. To address this, my work considers the history of the Rietveld pavilion itself and closely relates to its architecture. My site-specific interventions deal with the modernist architecture of the pavilion, its materials, lights, and shadows. Re-enacting class divisions inscribed in Dutch colonial architecture, as well as in Estonian manor houses, the work engages the viewer to reflect on the notions of hierarchy and privilege through the manipulation of the exhibition entrances. Talking about the venue as a space of privilege raises the question of hierarchy within the field of contemporary art as well. I see the venue as an effective stage that offers greater visibility. It’s such a privilege to have visibility as an artist and to use it for change, to talk about privilege and hierarchy, and to challenge them.

I have been left with the impression that you, Kristina and Bita, are both working with dualities in a sense. Bita, I am thinking of the way you have created two different paths for the visitors to follow in the space and your use of shadows. Kristina, in your films you explore dualities through the figure of the doppelgänger. How do you see that these dualities are received and experienced by the visitors to the exhibition?

BR: Fluidity and the transformations of the characters of our story brought the concept of duality to the works. In my installation, duality appears in every single element; natural vs artificial shadows, each visible for one of the two groups of audiences who enter the exhibition space from two different entrances. Additionally, my work includes a platform that acts as a space of privilege and enables two different perspectives – insider-outsider, perpetrator-victim – and the crossover between these roles.

KN: My film trilogy is essentially a set of intuitive images — three images of colonial processes, tensions, and transformations within inner and outer worlds of my imaginary Emilie Saal. I found the motif of the doppelgänger a helpful tool also to invite the viewer to consider the discussed phenomena from multiple perspectives. But above all, the doppelgänger motif is evoked to reflect on hybrid identities arising from colonial relations, from cultural transfer, from the fantasies and desires shared by the coloniser and the colonised.

The second part of the title, An Appetite for Abundance evokes a desire for lushness; however, there is a thin line between that and greed, in this case colonial greed. Within the context of this project, you show what happens when appetite becomes unsatiable hunger and how an individual’s desire for beauty is linked to much wider (global) mechanisms of extractivism. To what extent do you think it is possible to appease this appetite or is there any way this appetite could be subverted into something positive?

CA: The appetite part was inspired by a photograph created by Andres and Emilie Saal that I found at the Estonian Literary Museum. At the time, it was popular to make still-lifes of fruit that Europeans thought were rare; these were most likely seen as decoration rather than food. The photograph depicts an ornate image of an abundance of food and plants – it evoked ideas of hunger, hunting and collecting. However, the motivation for doing botanical art can be quite different. For example, the Indonesian Association of Botanical Artists, established in 2017, create illustrations that are meant to promote botany in a more direct and emotional way. They raise awareness about endangered plants and the need to conserve certain plants by actively holding exhibitions and online workshops to raise awareness of local plants in Indonesia.

Thinking of the allure of flower painting – there are ways in which beauty can be terrifying. Beauty is also intricately linked to power, either as a tool to achieve it or as something to be subjugated to it. However, beauty is not synonymous with sensuality or eroticism, yet Orchidelirium seems to include elements of all three – how do you grapple with the tension between these notions?

KN: In the context of Emilie's work, I think the notions of beauty and of danger are very much interlinked as they pertain to the realm of representation. In line with what Corina mentioned earlier in this conversation, beautiful, meticulous, painterly or photographic depictions of exotic flora have been used by Europeans throughout their colonial history to present tropical nature as fertile and yielding abundance as if by itself. These images continue to render the labour of indigenous people working in plantations invisible and silence the voices of those people and non-humans whose habitats have been destroyed earlier in history and are being ruined and exploited right now. In Western culture, the exotic is often connected to suppressed desires and sexuality. In my film trilogy, erotic energy is used to empower the agency of resistance and to fuel the subversion of colonial hierarchies.