When I began writing this essay, I was struggling a little to find a good word to characterise the way in which race has become a prominent and much debated issue in Estonian society. But the right word is not fascinating, ambivalent, or surprising. It is not surprising that race is increasingly perceived as a key problem in Estonia. Quite the contrary, it is no wonder at all.

When the Rendering Race exhibition (2021) in the project space of the new permanent exhibition at Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn became the focus of debates around race in Estonia, one could hardly say that it was entirely unpredictable, even if it was probably hard to foresee the heated public and private criticism on such a massive scale. The avalanche of negative reactions were centred on both the curator Bart Pushaw’s initial impulse to map and problematise early 20th century Estonian art in respect to race and colour, as well as the decision to change the previously racially charged titles for neutral ones. Taking into account the spread of the BLM movement in Estonia and the simultaneous growth in popularity of radical right-wing political movements and parties in the country, all of this is not surprising.

In parallel, Eastern Europeans are just beginning to realise that the memory of their trauma, the terrors of the Second World War and the memory of slavery exist in a shared space of remembrance and the two have been influencing each other in multidirectional ways. People with different backgrounds and positions are asking how we should think about decolonisation and critical race theory in connection this region. How can we find a method and a voice to use when speaking about the colonial realities of Eastern Europe and its decolonisation, while these concepts are defined by a mass of historical and theoretical work on the colonial and racial experience of the West? And is there such a thing as a specifically Eastern European colonial legacy?

History does not explain everything. Sometimes it explains hardly anything at all. Often, the best it can do is show us that things are more complicated than they seemed. Yet, in the face of the decolonisation debates, a look back at the complicated and dynamic history of Estonian identifications of race, whiteness and indigeneity might prove useful. It might even offer one explanation for the often painful reactions to the word race in Estonia.

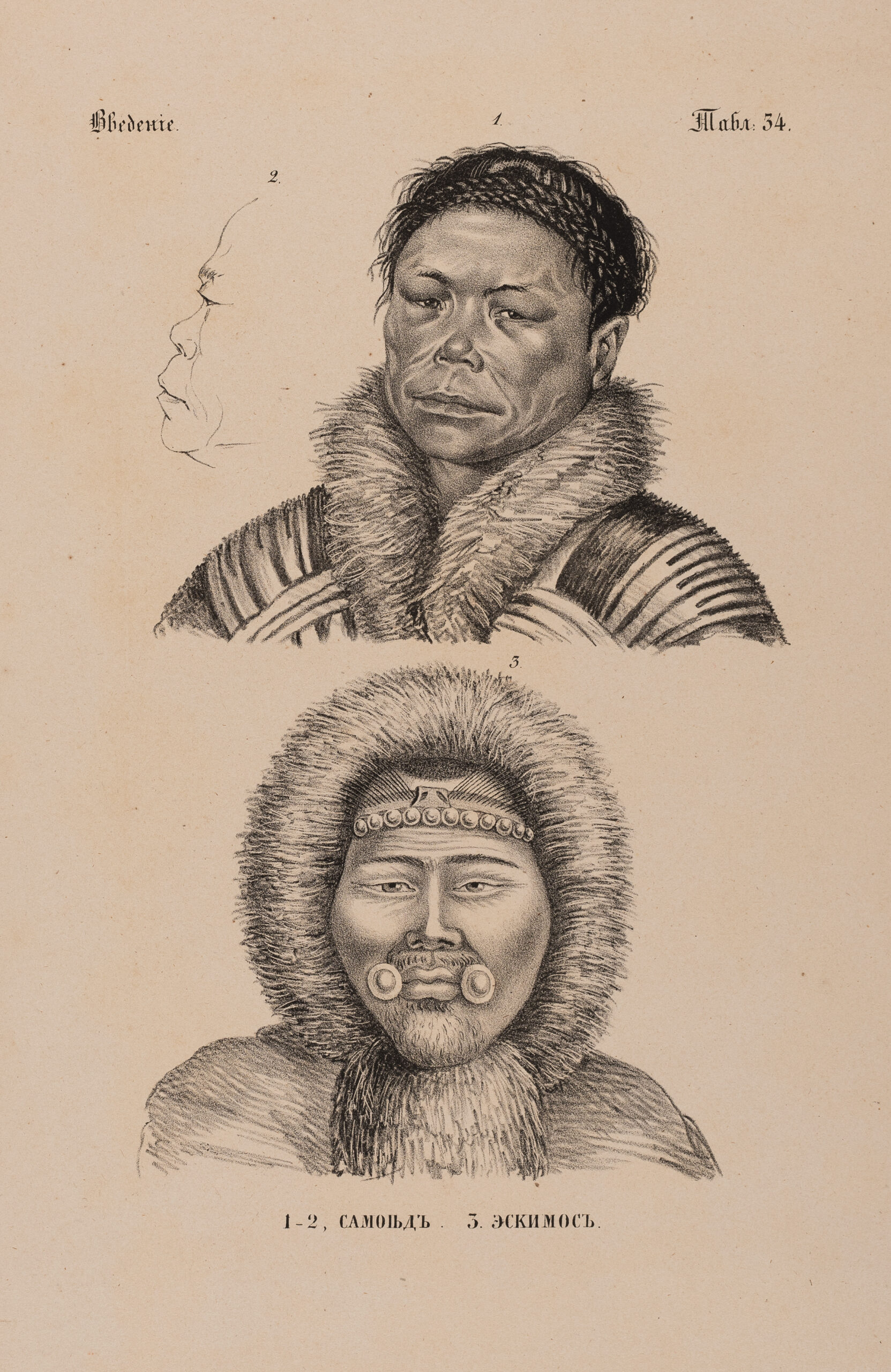

After the 13th century crusades, the Estonian speaking population was gradually turned into serfs under the rule of the German-speaking elites. From the early modern period onwards, they were also represented as culturally and racially inferior. Along with the spread of European colonisation, Estonians were more and more often compared with the native peoples of the North. Due to the Estonian language belonging to the same group as the Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic languages, the 18th and 19th century German authors eagerly associated the Estonians with the Finno-Ugric, but also other Nordic peoples, including the Itelmens, Inuits and other native peoples of America. In the late 18th century, Johann Gottlieb Herder famously called the Estonians the last savages of Europe and compared them to the Sami and Samoyedic peoples.

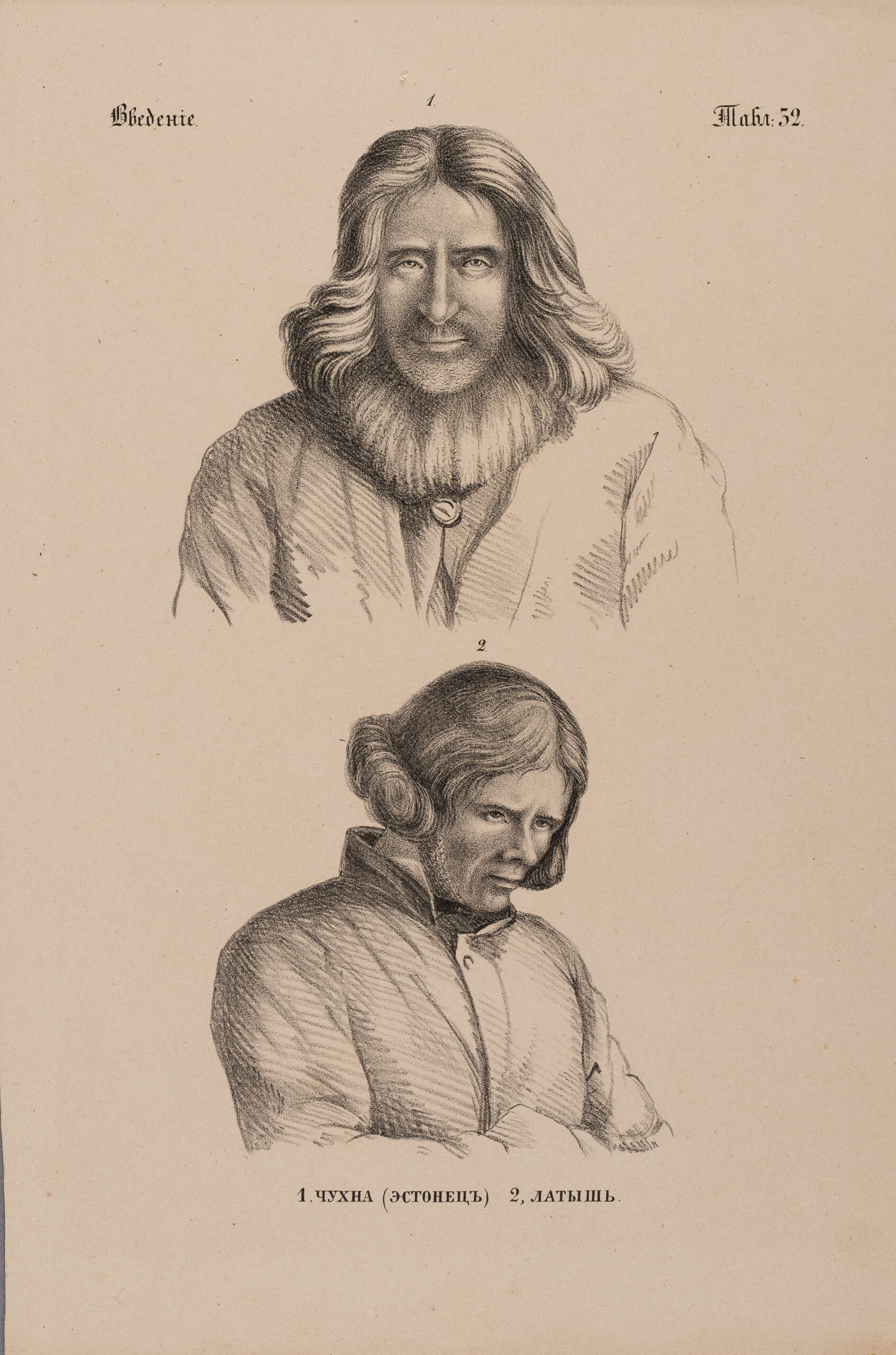

At that time, such comparisons, resulting in borealist stereotypes and arguments about Estonians being closer to nature than to culture also served to legitimate the socio-cultural segregation of the unfree peasantry in these lands that had become the Baltic provinces of the Russian Empire in the early eighteenth century. The Russian imperial ethnographic discourse placed Estonians somewhere between what its authors perceived as the savage natives of the North and the more civilised peasantry of its European provinces. While preparing the exhibition The Conqueror's Eye: Lisa Reihana's In Pursuit of Venus (2019) at Kumu Art Museum, we were struggling to find the origins of an image depicting Estonians and sought advice from colleagues at the Russian Museum of Ethnography. We discovered that the image originated from Julian Simashko’s Russian Fauna, or Description and Depiction of Animals occurring in the Russian Empire (Русская фауна, или Описание и изображение животных, водящихся в Империи Российской) published in St Petersburg in 1850–1851.

The Enlightenment writers and philosophers were the first to realise the potential of reversing the meaning of the native imagery, as they effectively turned their own vision of the noble savage into a powerful tool for criticising European nobility. At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, the Baltic German Enlighteners adapted these ideas. They also compared the serfdom of the Baltic peasantry to colonial slavery. From the 1860s onwards, the activists of the Estonian national movement likewise learned to use such analogies. Although the emancipation of the peasantry had taken place already in 1816/1819, it took the reforms of the 1850s to liberate the peasants from unfree labour and improve their socio-economic status. Among Estonian national activists, this resulted in considerable solidarity towards the slaves and indigenous peoples suffering from colonialism across the globe. For example, the first Estonian historical novels that were published by the leading national poetess Lydia Koidula in the 1860s were written about slave rebellions in the Americas.

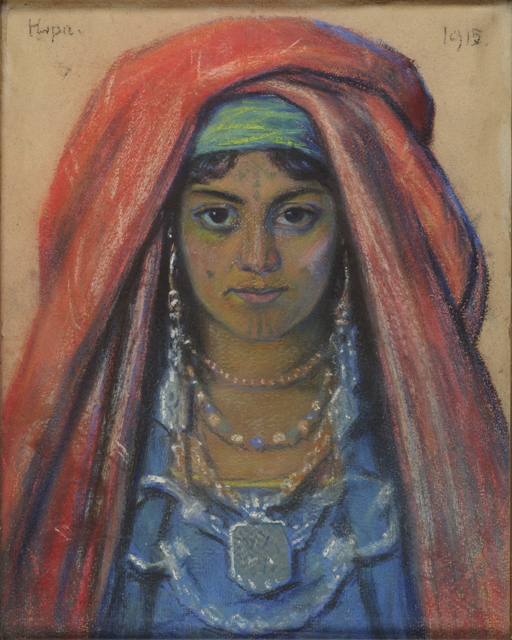

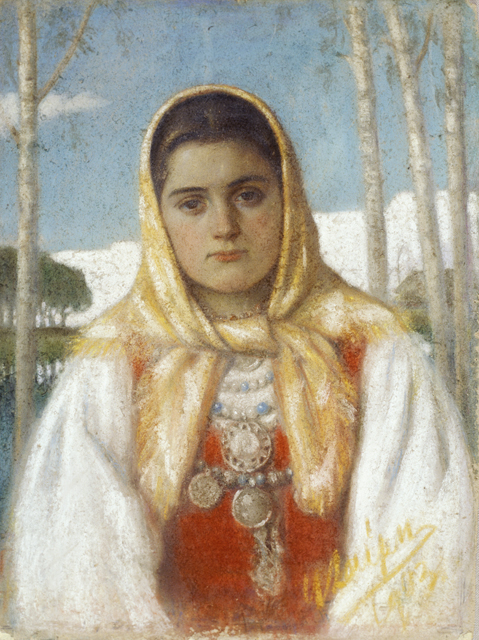

Elements of this solidarity with the oppressed and othered indigenous communities were still visible in the Estonian visual culture of the early 20th century. For example, ethnographic portraits by Ants Laikmaa depict with equal respect and sympathy the North Africans and the Estonian peasantry. But as the social mobility of Estonians increased and the nation state was formed in 1918, these associations became less frequent. Instead, Estonian visual culture shows a growing interest in racial differentiation, thereby raising the question of to what extent this could relate to how eager Estonians were to become white themselves. In the interwar period, narratives of slavery and associations with colonial slaves were gradually overshadowed by attempts to create a more victorious past for Estonians.

The question of what happens when the former colonised subject becomes the coloniser is central to the exhibition at the Estonian pavilion of the 59th Venice Biennale (2022) by Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi. The project, titled Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance looks at the life and work of the Estonian botanical illustrator Emilie Rosalie Saal and her husband, the writer and photographer Andres Saal, who became members of the Dutch colonial administration and thus part of the white elite in Indonesia at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. What happens when Estonians, who were just recently in the position of non-white native serfs, turn their gaze towards colonised subjects? How will their hybrid identities balance between the desire to imitate the colonial elites and show solidarity with the colonised subjects?

In fact, these questions are relevant for Estonian identity throughout the 20th century. Like many European countries, Estonia has witnessed a number of ruptures throughout the century, experiencing the founding of a nation state in the aftermath of the Russian revolutions, the loss of its independence during the Second World War, the Soviet occupation, and the regaining of sovereignty in 1991. A crucial element in reviving Estonian national identity in the late Soviet period was their identification with the small indigenous Finno-Ugric peoples. Living across Russia, from Karelia to Siberia, they still included communities with more traditional lifestyles and customs. There had previously been pan-Finno-Ugric movements, but only then did the idea of the indigenous roots of Estonians gain a wider resonance.

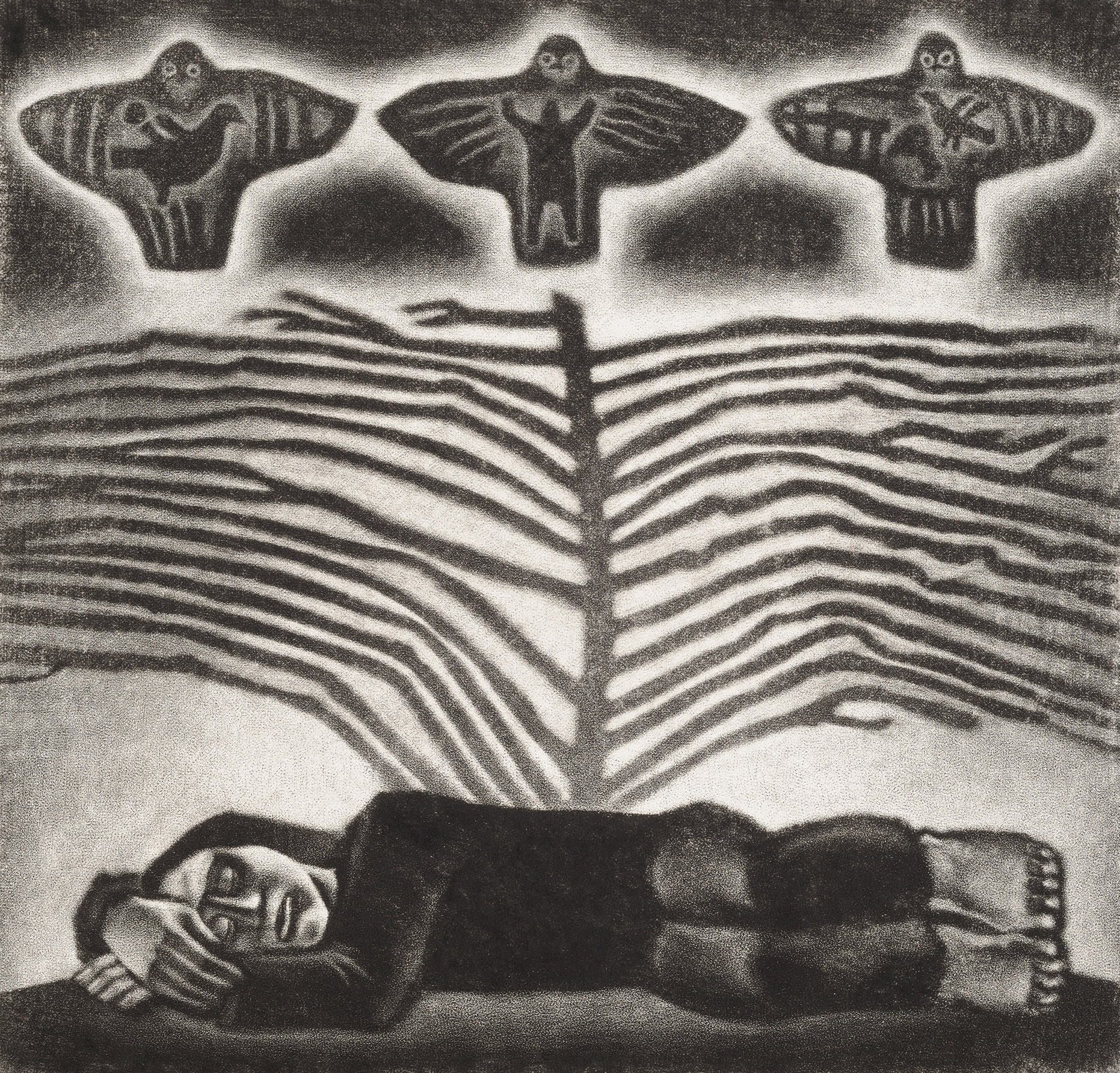

Crucial to this was the artistic research of prominent Soviet Estonian artists, filmmakers, writers, musicians in the 1970–1980s, including, for example, the writer and documentary film director and the future president of Estonia, Lennart Meri, the composer Veljo Tormis, and the artist Kaljo Põllu. The success of the Finno-Ugric revival among the rapidly urbanising Estonians was partly based on those authors’ skilful combination of the roles of artists and scientists. Teaching at the State Art Institute of the Estonian SSR from 1978 onwards, Põllu organised annual expeditions to Finno-Ugric peoples with his students. He also cooperated closely with ethnographers, linguists, and other academics.

The relationship Kaljo Põllu and his contemporaries had with Finno-Ugric indigeneity was in many ways controversial. On the one hand, they differed from the Western gaze, taking a step further and identifying themselves and their nation with these indigenous cultures. On the other hand, they did not position themselves as indigenous authors either, but rather took the position of intermediaries. They remained at a safe distance, maintaining their position as the more civilised, modernised white brothers to their Finno-Ugric Siberian siblings, who embody the authentic roots of Estonians.

Why did the white Estonian artists, writers and filmmakers re-fashion themselves as natives in such a serious, scientific way? Their turn towards indigenous cultures resonates with a broader fascination with heritage and folklore, emblematic of the last decades of the Soviet Union and often explained as part of the disillusionment with the Socialist utopia after the suppression of the Prague Spring – the anti-Soviet uprising in Czechoslovakia in 1968. This trend, however, coincides with a more global crisis of industrial modernity and also the rise of environmental awareness. In Estonia, the propagators of Finno-Ugric heritage cooperated with environmentalists too. The latter, in their turn, adapted the identification of Estonians as indigenous people, often comparing them to native Americans and other colonised peoples (who had become icons of environmental movements also elsewhere).

During the collapse of the Soviet Union, the idea of Estonians as indigenous people and comparisons with other native peoples gained a new momentum. As in other Eastern European countries, Estonian environmental and national activists alike drew comparisons between extractivism in European colonies and the exploitation of the Estonian and the other Soviet republics’ resources by the Soviet Union. This gave the idea of the indigenous identity of Estonians a clearly political dimension. During his presidency (1992–2001), Lennart Meri continued to emphasise these connections; for example, comparing Estonians to the colonised African peoples in the United Nations assemblies. At the same time, central to Meri’s speeches and understanding of history was the idea of Estonia as an outpost of European and Western civilisation on its Eastern border. This vision also has telling contradictions, as it presents Estonia simultaneously as a representative of the indigenous colonised subjects and their European colonisers.

The ambivalent desire to be white and indigenous at the same time seems to characterise Estonian identity in a broader sense – and the internal tensions resulting from this hybrid identity might also explain the painful reactions to issues of race and decolonisation. As stated above, one way of solving these anxieties might be to work through the multi-layered histories of these identifications.