When you encounter the art of Anu Põder, the first thing you are likely to feel is: Her work speaks of life in a manner so lucid and intense that what it says must be directly taken from life. It addresses the pain of coming to pieces, as well as the power of personal growth, in a viscerally existential, bodily way. In doing so, Põder breaks with how the canon of modern art, written by and for men, has defined the form life has to take on in art: that of a linear career, which makes a red thread emerge, as artists master adversities, and sum their findings up tidily and tightly in one coherent body of work. The pressure to fit this form is still on, maybe more so than ever, as social media rewards the compact packaging of art and life. With Põder things take a different route. To develop a passion for her work is to appreciate how she deals with life interrupting art, as she returns to making pieces in intervals, while parenting, and making a living. Following this existentially syncopated rhythm, she revises, twists and layers her work in incredibly vibrant ways. So the body of work Põder creates during her lifetime is not governed by one rigid concept of identity. It grows and diversifies, in step with life changing.

The extended version of this essay develops this critique of canonical career thinking on art and life in a slow meditation. This abbreviated edit now focuses on key aspects of violence and growth in Põder’s art. Her work testifies to pain inflicted on body and soul. And it speaks of empowerment, yet not in terms of victorious mastery. It won’t resort to a linear heroic tale of conquering pain. In revising, twisting and layering work, Põder instead shifts the weight of pain. It stays there, but comes to exist alongside the power to grow, undenied, acknowledged, addressed, and as such, adding momentum to a counter-push towards living, and growing, as the interplay between weights and forces remains in motion:

[…] Emptiness (Tühjus, 1985) seems pivotal in that in this work Põder pushes her approach to breaking bodies apart to a limit where the violent quality and traumatic dimension of the work are fully disclosed. In this piece, different textile objects and rounded amorphous shapes are strapped to the wire mesh of a metal fence using long ropes. Amongst them are patches of crinkled textile that look as if they could be the filling of the more voluminous of the shapes. So you perceive them as intestines spilling from lacerated body parts. At the centre of the assemblage Põder has mounted a sheet of pink plastic moulded in such a manner that the outlines of a female torso (breast, collarbone, armpit, hips) can be traced. Yet this body has next to no volume. It’s as if its skin had been stripped and discarded like a piece of clothing which, in its bulges and crinkles, still suggests the curves and folds of the body it once covered. Dismembered, gutted, skinned and left to dry on the fence, this body strikes you as having been subjected to extreme violence. In the history of sculpture, the torso can be seen as being associated with various romantic ideas of beauty (in ruins). But here we are looking at no headless Heracles. In Emptiness the fragmentation of the body speaks of actual dismemberment. In doing so, the work doesn’t merely represent trauma. It enacts it. Strapping the resemblances of dismembered body parts onto a metal fence around the skin stripped off a torso brings the traumatic force to bear. The impression that Emptiness leaves firmly imprints the connection between violence and fragmentation on your memory.

[…] Fast forward to future work and the sense of traumatic force may, likewise, stay with you when you see the tall textile figures Põder sculpted between 1992 and 1993. Many (not all) of them have a head and limbs. Indeed, they seem to express a sense of recomposition, of getting things back together, getting ready to move and act. Still, the imprint left by pieces such as Emptiness, continues to haunt even these sculptures. After the force of the fragment hits you, no body in Põder’s work will ever look whole again. Something keeps tearing at them. Coiled (Keerus, 1993), for example, is a tall female figure, its skin made from layers of blue fabric strips, as if it were bandaged from head to toe. As the title spells out, the arms and legs of the figure are coiled. The arms look like the horns of a ram. The legs are twisted around each other like two ropes. The figure palpably exudes an immense tension. It looks torturous.

Yet Coiled only looks like a body in pain when we read its limbs as being coiled and twisted inwards. What if we pictured the re-coil of the limbs un-coiling and releasing their tension? The figure would pivot around itself and unleash the force of a whirlwind. What looked painful from one angle, appears incredibly powerful from another. Are we confronted by actual pain? Or power in a state of potential? Both readings seem valid. So again, here, we have a turning point. From the position of the work, different aspects of previous or future works may once more come into view. Pain or power? Or both? Looking back at works from the eighties, the amazing On One Foot from Lasnamäe (Ühel Jalal Lasnamäelt, 1986) jumps out. The sculpture is made from two, slightly coiled, entwined plaster tubes covered in patches of skin-coloured leather from which metal spikes protrude. […] There are many of them, and they have definitely become weapons. As Estonian sculpture historian Juta Kivimäe explains, the title of the piece alludes to a ride across town on a line where the buses are notorious for being overcrowded. As bodies fight for space, limbs rub up against each other and get tangled; everybody has their spikes out, limbs become weaponised, pores grow thorns. This is fierce. And funny. And very close to life. A life not merely defined by suffering but by an urge to fight back and persist. These spiky body parts – in the mode of becoming weapon – express an insistent will to live. Spinoza called it conatus, a lust for life, or rather, the sheer power to persevere. Every spike speaks of it. And so do the coiled limbs of Coiled. Twist me? Watch me uncoil and fly in your face! When you look at it this way, the tension that the many bodies in Põder’s work exude, could very well be a result of the pressures imposed on them. But it could equally be perceived as the powers of life, ready to release themselves.

The release could, but may not have to, come in the form of violent assertiveness. It could also take on the form of growth. Look at Composition (Kompositsioon, 1988). With its many curves and folds, this plaster sculpture painted green looks like the most potent form of otherworldly life, a mollusc with multiple sexual organs and orifices. Have you ever seen an octopus move on land? Its jelly body seems to shift shape every second as it slips and slides onwards: an intelligent organ in motion. Indeed, when in Composition we move from the fragment to the fold, a whole universe of expansive being opens up in modes of unfolding, unfurling, uncoiling. In Long Bag (Pikk kott, 1994), a long train of cloth unrolls across the floor from the silhouette of a woman made from the same cloth. She seizes the space effortlessly with the matter her body produces. This is power. What do we see if we now look back upon the pieces that primarily read as manifestations of traumatic forces? They will still manifest trauma. But another dimension of their materiality may yet reveal themselves. Inspired by Long Bag, we might imagine what Emptiness would look like if, like the cloth trailing across the floor, the wire mesh fence were in a horizontal position. Would it not make the structure resemble a bed and the stuffed objects cushions, the crinkled fabric blankets and the discarded skin a jacket cast on the floor upon which to sleep? If we were to look at it like this, the piece would still speak of a fight, but from this perspective, the struggle would be one of making a place for bodies to rest.

Not just any artwork is capable of engendering such twists and reversals. I would argue that it takes a particular kind of power to express the conflicting dimensions of life in such an intimate manner, in layers that open up progressively and retroactively. It may be persistence that keeps someone journeying back and forth in the depths of lived, embodied memory. But when it comes to the manner in which Põder manifests these forays into the depths of life, it’s striking that, persistent as they may be, duration as such does not seem to matter. Engaging with her work is not like reading Proust or Joyce, who translated their memory mining into overwhelmingly detailed accounts that take an age to read and probably took even longer to write. Põder’s timing is different. Her works are crystalline, they contract a whole world of conflicting nuances into concise forms, which then keep shifting before you, like glass shards in a prism. In this sense, her pieces are much like Clarice Lispector’s novels. They are short, explosive, deep and dense. In all their brevity, they venture to the core of the Earth and back, time and again, in the glimpse of an eye. It’s the timing of mystic thoughts that hits you, sharply, while you are immersed in matters of the material world. “I capture sudden instants” Lispector writes in The Stream of Life (Água Viva, 1973), “that bring their own death with them and others are born – I capture the instants of metamorphosis, and their sequence and concomitance have a terrible beauty.”

It takes guts to expose oneself to such reversals and clashes by exploring the depths of embodied memory in one’s art. In this sense, Põder’s work is truly gutsy. Infinitely more so than the work of many artists – traditionally most of them male – who avoid the shock of realising that nothing was or stays quite as it seemed, by hammering out the selfsame identical type of work: the work which, at one point in their life, they thought was a good idea to make, and which they henceforth make for the rest of their lives. Art history unfortunately praises as ‘consistency’ what may amount to little more than a man’s fear of confronting the fact that the tectonic plates below him are constantly moving. (For if he dared dig deeper, the layers of his work might actually start moving too.) I would read Põder’s Man’s head with a flag (Mehe Pea Lipuga, 1984) along these lines, as a mockery of the fearful narrow-mindedness that accompanies a stereotypical man’s craving for clear focus in life. The piece resembles the head of a man, all but eyes and mouth covered in pink leather, as if he were clad in chain mail or some futuristic form of helmet. At the top of his head there’s a flag ready to point wherever the wind is blowing. From the rear of his neck strange bulging shapes protrude, writhe and wrap around the back of his head. Oblivious to the ghostly occurrences his own body produces behind him, he looks ahead, unmoved, unperturbed, with an air of great resolve, ready to march into battle or take on ‘great projects’. Oh, what a fool. If you are raised to fight your way through life like this, like a man, other men will keep asking you what position you take, what ideas you represent, what ideology you focus your energies around. They teach you to confuse life with whatever sign you could put on a flag to signify what you stand for. As if that is all there is. What else there might be would be easy to perceive, if only you took off the darn helmet for a second and recognised what was going on behind you and all around you, all the time.

[…] Experiencing the reality of your surroundings with this enhanced sense of awareness, asks for other responses: no grand resolutions, but the intimate engagement with the forces that shapes life in relations. So in Põder’s works, forces tearing bodies apart clash with forces that make them grow spikes, fight back and expand beyond measure. The work is fierce, forceful, and full of unappeased difference and unconsolidated non-identity. In short, it is too fierce to be recuperated by conclusive words of appraisal. As the life work of an experienced artist, meaning the work of someone who has lived her life to the fullest, it would seem these artworks need no appeasement. They ask for guts, to be grasped and grappled with, in the course of ongoing encounters.

An earlier version of this text was published in Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!, a book accompanying an exhibition of the same name at Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn in 2017.

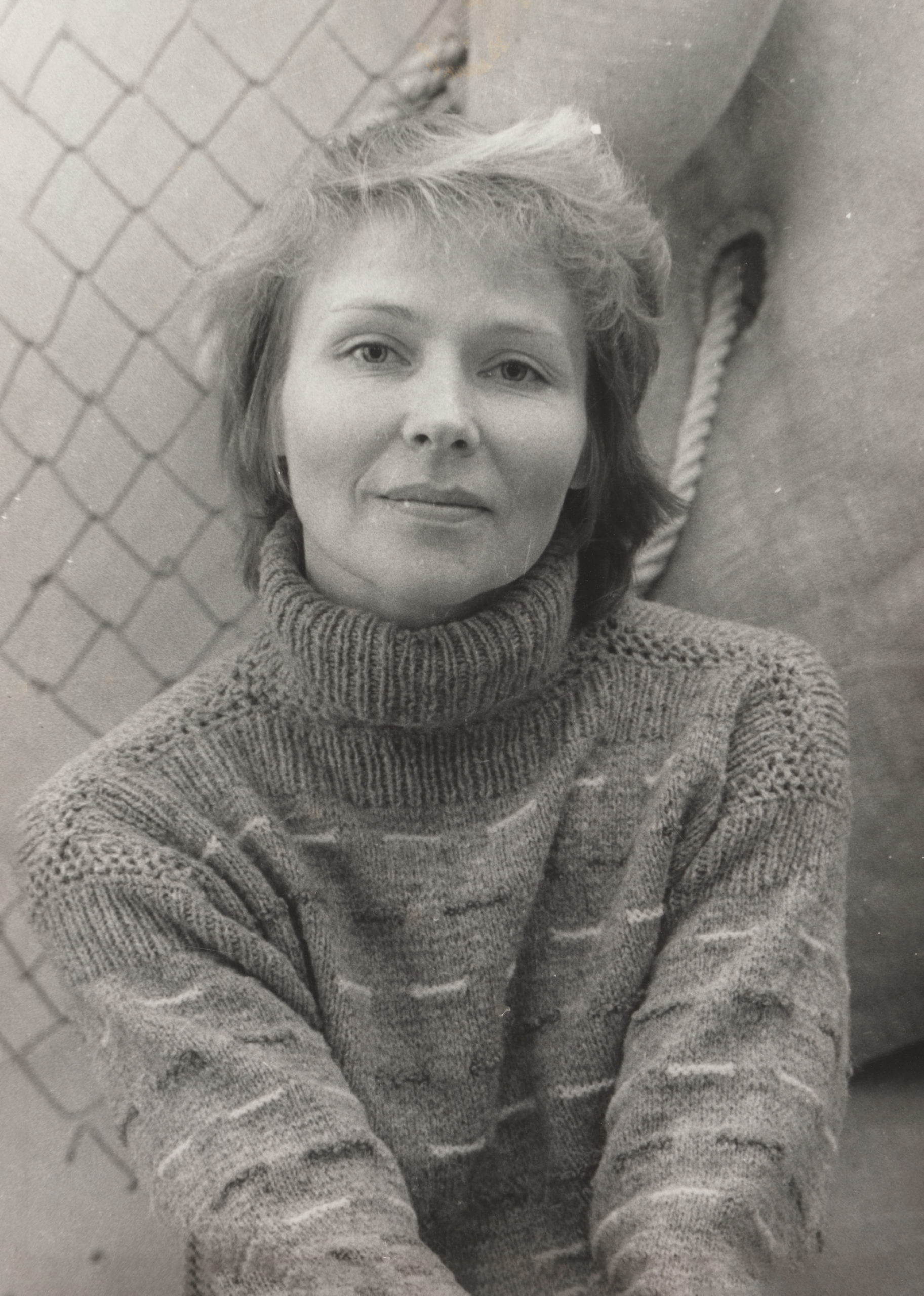

Anu Põder (1947–2013) was an Estonian sculptor and installation artist. Throughout her career, she experimented with new abstract forms and a variety of materials from plaster and wood, charcoal and textile, to light, scent and taste. Põder’s work was inspired by her own experience as well as her surroundings and environment in the city and in the countryside, at home and at work.

She studied at the Estonian State Art Institute’s sculpture department from 1970 to 1976. Until 1986, Põder worked as a freelance artist and after that, shared her time between her artistic practice and her students at the Estonian State Art Institute and Tartu Art School. Põder’s works belong to the collections of the Art Museum of Estonia, Tartu Art Museum and to her family. In 2021, the second original version of the work Tongues (Activation Version) (1998) was acquired by the Tate.

In recent years, Anu Põder’s work has been exhibited at Kumu Art Museum (2017), 13th Baltic Triennial in Vilnius (2018), Pori Art Museum (2019), La Galerie Noisy-Le-Sec in Paris (2019), and Liverpool Biennial (2021). Three works by Anu Põder are presented at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia Milk of Dreams (curated by Cecilia Alemani).