I’m leaving rainy Helsinki behind and approaching sunny Tallinn, where I meet Sarah at her studio, and Maria Izabella is joining us on zoom from their studio in Mainz. Maria Izabella and Sarah’s show Hardcore Gentleness is about to open this summer at Vent Space in Tallinn (28–31 August), and we’ve agreed to chat about art and life. I’m thinking of their works and themes of desire, intimacy, safety and sexuality, as my body is soaked to the bone in overflowing infatuation for someone I spent last night with. I’m looking out the window of the Tallink Megastar ferry, and waves of love wash over me. It’s a good day to talk about thirst and connection.

To start off, I just now realised there’s a meme that funnily relates to your practices: Maria Izabella you’ve used nail clippers as elements in Your Brain is a Bedroom, and Sarah you’ve used body hair and hair as material. In the meme there are two images, before and after. The first says something like My pre-date ritual before, and the latter My pre-date ritual now. The before-image depicts shaving armpit hair, and the now-image depicts cutting nails. I think that’s a nice meme in relation to your practice, as you’re dealing with body image and patriarchal standards of beauty and desirability, and sexuality of course, as cutting nails in this case refers to queer sex.

Sarah Nõmm: Haha yes! I think hair is a very stigmatised material, when it’s anywhere else than hair, eyelashes or eyebrows. I feel every person who tries to fit the normative has had problems with body hair growing. We all have responsibility for normalising body hair and taking the perceived grossness out of it. Like sometimes when I go to parties, and I have armpit hair, people just pull on them, and I’m like "what the fuck!” In my practice, I’m using it as a symbol that carries a variety of meanings. I’m trying to actively fight the norms regarding body hair and bodily expression.

Also related to bodily expression and the body as an active subject, how did you, Maria Izabella start working with imagery of boxing, the hitting hand and boxing gloves?

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: Boxing was initially a hobby of mine, something separate from art. When art became work for me, boxing was something that differed from that, something physical. I had been interested in it as a child already, but I wasn’t allowed to do it, I had to do dance classes. So now, as a grown-up I wanted to start. And then it found its way into my art: the boxing gloves and the wrapping and hands came naturally. I see myself as if in a first-person shooting game, that’s how I see myself in my daily life, hands are the first thing I see of myself. It was interesting that for an artist, hands are such an important tool, and in boxing hands are a boxing tool and a protecting tool. In boxing, hands have to be protected, and at the same time my hands are protecting my head. It’s interesting to think how they have a double-meaning: to protect and be protected. The boxing studios that I’ve been to haven’t really been that inviting though, I haven’t felt I belong to those clubs.

Sarah Nõmm: Yeah, I’ve always been fond of boxing because my dad was a boxer in the late 90s, but I’ve also been discouraged from going; the energy in those spaces is a bit different to what I’d like.

Is this something that you find in other fields in life as well? You’ve mentioned earlier that you find the art field very masculine-driven, or that the energy might not be the most inviting for you? How do you see yourselves in relation to the field: do you see there is space for you?

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: I’ve always felt isolated because of the topics I deal with, like mental health or my queerness, and other people don’t really know how to talk about these topics. Overall, my life experience is quite isolated because I’m neurodivergent, so I feel I have to mask in order to fit into spaces. It’s been funny to me to feel that double-down in art spaces.

Sarah Nõmm: At the Estonian Academy of Arts, some departments are a bit masculine-driven. I remember an instance, when I had a conversation with one of the professors and tried to make him understand why I’m working with body hair, trauma, relationships, sex and BDSM, and he said "I can see these feminist topics are now in fashion.” I could always almost hear his thoughts, he just didn’t understand, and it was hard to find a common ground. These are not just topics that are "in fashion” but they are actually important and need to be analysed and talked about.

In the field in general, it has been a relatively nice experience for me, as it has been slowly changing for the better. Also because of the internet, it’s quite easy to connect to others that are thinking about and working with similar topics, and there, find a sense of sharing.

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: The main reason why I didn’t stop talking about the things I deal with, was that it’s so nice when someone thanks me and says they feel the same but haven’t seen any representation before. It’s humbling and warms my heart if I can provide that space, create a little corner where those things are addressed.

A lot of times, you make something and you never hear what people have felt or experienced. But it’s so valuable!

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: I’ve even made friends with people who’ve reached out via Instagram and commented on my work. I think it’s really typical of the Eastern European queer experience to connect online and that community is really important. And even before Covid the community very much existed online.

Sarah Nõmm: The energetic impulse from others is so important; an artist really needs that. But it’s a basic human need too.

I’d be curious to know what you’ve been thirsting, yearning after lately?

Sarah Nõmm: Ah, very primitive things, like love and lust, funky human connections. I live for that connection.

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: Maybe it’s basic but mutual understanding. It’s so exciting when someone’s on the same page as you. I haven’t felt so understood in a long time as I feel now by someone. And also, after isolating, basic physical connection, like hugging someone, non-sexual touch, I love it.

For me, they’re very much the same things. Sometimes an intellectual connection, like having a deep, sharp conversation with someone who knows what you’re talking about and you get new ideas from them and you’re like, wow, my mind is blown, like these brain orgasms. But I’m not always up for that, I guess I’d say that anything that gets me to the next level, somehow accelerates or changes the mode. But always love! When thinking of love or sexuality or wanting to make a connection, how do you see artistic practice fitting into all of that? What is the impact that your art practice has in your life? Because sometimes I think my motivations for making art are very selfish, like I want to do something in my life and that guides my practice. I want big changes but also really small ones. Once I even built a whole exhibition around the desire to spend time with an artist I had a crush on. So artistic practice is like a vehicle in my life to get connected and to process that need.

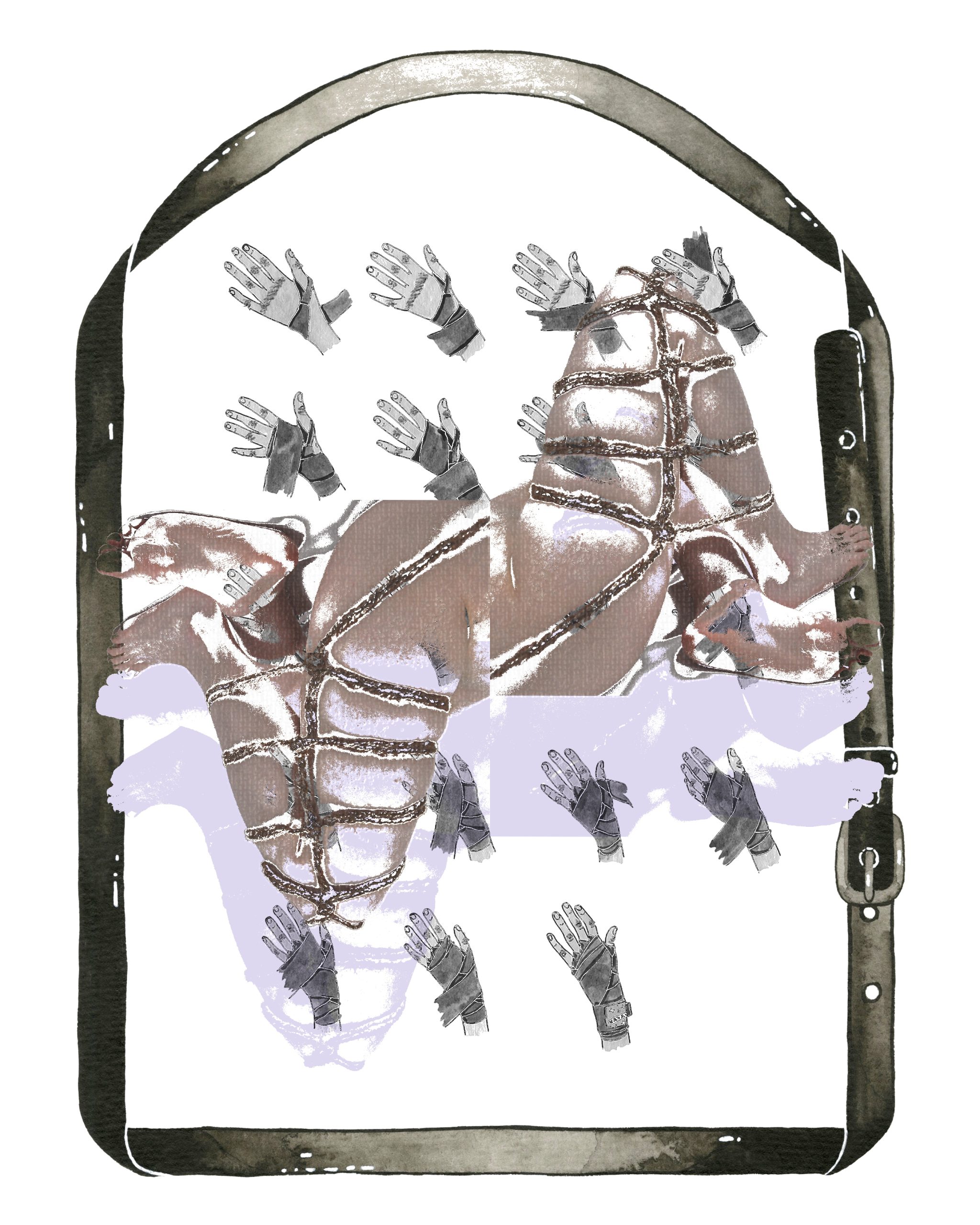

Sarah Nõmm: These needs and wants are definitely very intertwined. I’ve started working with shibari as a symbol. I like shibari as a pleasurable act, but through art I can dig deeper and make time for it, and also interpret it in an artistic way. And when I started thinking of non-monogamy and doing research on that, I met a girl who was polyamorous and I fell for her, and it all came together. In shibari, the safety aspect is so important, the feeling that someone is holding you. And since hormones are involved – rush of endorphins – it’s very addictive.

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: For me too, even if I wouldn’t want something to become a project, I still somehow vent through creating. At first, my art practice was more about me venting, but at one point I found myself accidentally retraumatising myself, so I had to step back and think through how I want to represent myself through art. It’s only quite recently that I’ve twisted the narrative in a way that it’s not so much about me anymore, and that feels healthier. I started detaching myself and made an alter ego, Mesimagus, that’s like a third person presenting something that’s not personal. It made me more interested in making art.

Yeah, when dealing with personal stuff in art, it’s very fragile and very delicate terrain. You get lost or broken easily if you leave yourself too exposed.

Sarah Nõmm: Every time I put something out there, I feel like I’m standing naked in the gallery, and everyone else is wearing clothes. But for me it gets gradually easier to be naked. Maybe there’s some masochism in there, it’s very therapeutic.

For me, it’s a very mixed feelings situation, like feeling deeply ashamed and excited at the same time. Being like "look, here are my insides”, but feeling terrified and super embarrassed. In relation to being fragile and terrified, do you think that it is possible to build structures for oneself that support in this aloneness? Was the isolation project, Loveless 2, for example, a way of creating a safer space for you?

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: Isolation came from a personal need, as I found out I am neurodivergent. I felt alone, and I wanted to think about what a safer space is for me, being a queer person as well. The new me didn’t fit with the ideas many people in my life had about me and I had to cut people out. Through this project I found a way to be vulnerable again, and to be surrounded by people.

Sarah Nõmm: The power of being vulnerable!

I’m thinking of the title of your upcoming exhibition, Hardcore Gentleness. Do you think the world is ready for hardcore gentleness?

Sarah Nõmm: My pink cultural bubble is quite safe, but when I’m outside of that bubble, it’s a very scary world. The world is not accepting of vulnerability, but we’re taking baby steps.

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar: The term world is funny, but when you take the courage to be gentle in a hardcore way, the right people will find you, and you will form your own little world.

Maria Izabella Lehtsaar is a Tallinn-based artist, working primarily with themes of queer experience and mental health, often exploring the fine line between reality and fantasy. Their works and motifs are simultaneously modest, loud and captivating. They blend pop culture aesthetics and sensitive black-and-white graphics, combining them in textiles, drawing and text.

Sarah Nõmm is a Tallinn-based artist, working mainly in the media of sculpture, installation, video and performance. Her practice focuses on the woman's body and the spaces around it. Her works are often based on personal experience and look at the body in the context of folk traditions, myths, taboos and everyday rituals, while also analysing the underpinning gender inequality. She often uses traditional handicraft techniques in her practice, such as spinning yarn, felting and weaving on looms.