A sly, almost crypto-surrealism pervades the paintings and serigraphs of Estonian artist Malle Leis (1940–2017). Somehow simultaneously immediate, quotidian, and observed, but also fluid with rainbow waterfalls, unmoored botanicals, and landscapes emerging from people in other dimensional spaces. Her work flirts with pop, with everyday intimacy, and with the codedly erotic within floral fantasias and stylized portraits of friends, family, allies, and vividly coloured horses in angled postures and often uncanny flatness (a bit Alex Katz, a bit Tamara de Lempicka, a smattering of Frans Snyders and Lisa Frank, but both sweeter and more sour than any of these), sometimes blending into landscapes and later those visions of nature without figures at all.

When asked to list her favourite artists for her retrospective catalogue in 2014, she cited Russian turn-of-the-century bête noire Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (especially his star turn naked atop a horse in Bathing a Red Horse, 1912), the 19th century realist grandee Ilya Repin (lately famous for his Reply of the Zaporzhian Cossacks, 1880–1891, as an echo of the resistant fuck-you the Ukrainian people gave and are giving since Russia's 2022 invasion of their homeland) along with lusciously floral Ukrainian folk artist Kateryna Bilokur and the flowery southwest folds of American painter Georgia O'Keefe. The artist curiously and explicitly states in the same interview that she’s not a feminist (though it’s unclear if it’s elder revanchism or a lifelong fundamental stance), there’s a distinctly bold femininity that connects to the latter two female artists. In the case of Bilokur, who, however exquisite her paintings are, was an untrained artist from a folk background, and proto-feminist O’Keefe, one feels a bold and brave femininity in both of these women’s work from the folkloric to the avant-garde that emanates from Malle Leis’ oeuvre but always with a blinding colour.

It's difficult to summarize any artist working for nearly five decades, but we can trace her polychrome vivacity to the graphic angled framings and all-over compositions bursting with plants from the 60s, her portraits from the earlier fundamentally representative to the latter much more specific figures, and those landscapes from the psychedelically unreal to the sweetly twee. Those otherworldly angles sometimes set aside vacant backdrops for her brushy voice to be laid bare upon arching winter birches and autumnal foliage.

Her work from the 60s and 70s, probably her most well-known, beams with life; the brightest colours possible squeezed out in response to the grey backdrop of the basement she painted in and one assumes the stultifying, bureaucratic grey of Soviet-occupied Estonia. In her youth, there were sneaky overnight trips to chill with the non-conformists in Leningrad and whispers of psychic liberations wafting over borders. I’m not sure Malle Leis would ever consider herself a Soviet hippie, but for me there’s definitely a vibe. Whimsical, bold, playful, her diptych Red Horses (1972/4) is totally emblematic of this moment in her work: a bent and smeary double rainbow arcing over two red horses (echoes of nudey Petrov-Vodkin and his equine wash) with rich blue bridles backdropped by an utterly flat pale blue sky. Astride one horse, a young woman with red hair gently breezing, wears a pale poppy orange t-shirt and shorts matching her hair, barefoot and smiling. Over a blue enclosure that foregrounds the painting, a trio of Kelly green clovers drift by in the wind. It almost feels naive in its carefree wonder and is utterly loveable for it.

It’s probably valid to say something about horses and suppressed/emerging female sexuality here, and of course the same goes for Leis’ most beloved subject: flowers. But I’ll gently evade any Freudian speculation, and say simply that these don’t have to necessarily symbolize anything but that they inspire so many feelings connected to the erotic that they are just a tongue-lick away from sexy (And I’ve never been a woman riding a horse, so I’ll let others speak on that specific sensation). But flowers and fruits were always the sex organs of plants. When animals first stumbled out of the ocean, the exclusively green foliage evolved into the fleshy and flowery to attract creatures (from insects to us) to better propagate themselves. Or to put it more simply, flowers re-invented themselves for our pleasure. And sometimes fearlessly unfurled or tightly deployed, there is always pleasure here.

While one gets the feeling that Malle Leis must have glimpsed the print Flowers (1964) by Andy Warhol, if she did spot this famed screenprint in the wild, whatever ideas she plucked from it took on a very specific form as she clearly had a botanist’s eye for the details of the various fruits, flowers, and sundry plants that leaf, curl, and bloom through her flat and fulsome pictures. While Warhol was generally interested in celebrating the banal, flipping the high artiness of it all upside-down, looking at Malle Leis’ flowers, she found in the simply vivid hues a subject to obsess over, endlessly refine, hone her style. You feel her care and connection in every great mullein and rose. The stylized simplicity is never quite shed from her portraits, but her flowers (without forgetting their origins in idealistic pop) become ever more particular. They begin in the 60s fluidly abstracted, but become with each passing year almost slavish in their detail. The flowers lose their specific place in the mundane and their context disappears into emptiness, from hard black and sky blue to atmospheric cloudy green, while the blooms became ever more precisely rendered. A similar phenomenon occurs in her portraits, the softly idealized become ever more specific, reaching their apotheosis in the bird’s nest tangle of a beard in her portrait Raul from 1990.

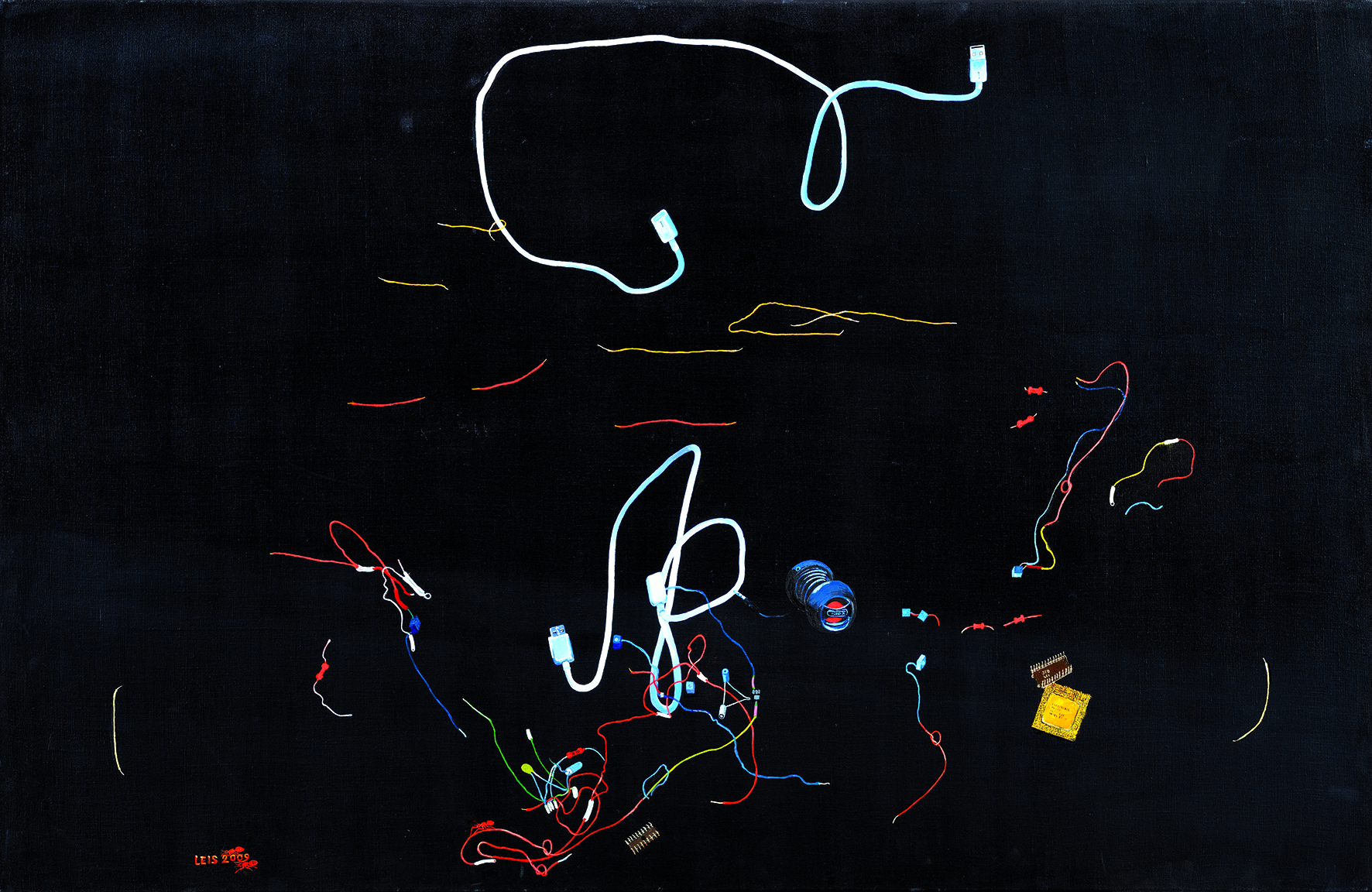

But let’s step back for a moment to Leis’ flowers, the sheer lush open squirm of all these blooms deserves a moment of reverie here. Petals like speckled goldenrod tongues loll out alongside tightly packed and plump buds ready to burst (Anais Nin: "And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.”). Stamens bulbously pop and perfect leaves wave sharp as cut crystal. Strawberries plump from pale green to lusty red along writhing stems tenderly rendered. Roses already bursting look coyly about to lose their petals like dropping their first veil and at other times tumble, cut from unknown heights against inky black skies. Leis’ all over 60s flower fields and her explosive use of colour becomes tightly contained within these folds. By 2009, these monochrome backdrops let go of flowers for a canvas or three and confronts modernity. Those fluid stems and bright blooms in New Brave World II, 2009, become wires and cords (I think I spot a duo of USB-A cords and a golden microchip) and this take on modernity is hard to read. Is it a hard response to the primacy of technology or turning her botanical eye to a new crop of colours blooming from every laptop and cellphone? This painting with its precision and composition, its uncanny atmosphere has moments from the same strange world of German painter Monika Baer.

Whilst they echo the scientific detail of botanical drawings and take on some of the early Renaissance Netherlandish obsession with precision in the plant world, they never quite lose their 60s Pop potential. And though a professionally trained artist, you can feel her work wavering between some contemporary international sense of art, the layered history of painting, and the native affections for the folkloric, trying to find her place in a shifting world. But no matter where Leis found herself throughout her career from Soviet nonconformity to feeling ignored during Soros-era art funding to her late-career revival, you feel the courage of her colours and the potential of prismatic light in every luscious petal.