Eha Komissarov is one of the mother figures of contemporary Estonian art – a legendary curator and critic, celebrating her 50-year anniversary of working at the Art Museum of Estonia. She started at the museum in the beginning of the 1970s. This was a decade, when the local art field was slowly becoming more diverse after Khrushchev's Thaw. Since then, art and the world in general have radically changed – the fall of the Soviet Union and re-establishing Estonia's independence in 1991 brought a complete re-conceptualisation of art and the art world as well as rapid changes in society, orienting itself toward capitalism.

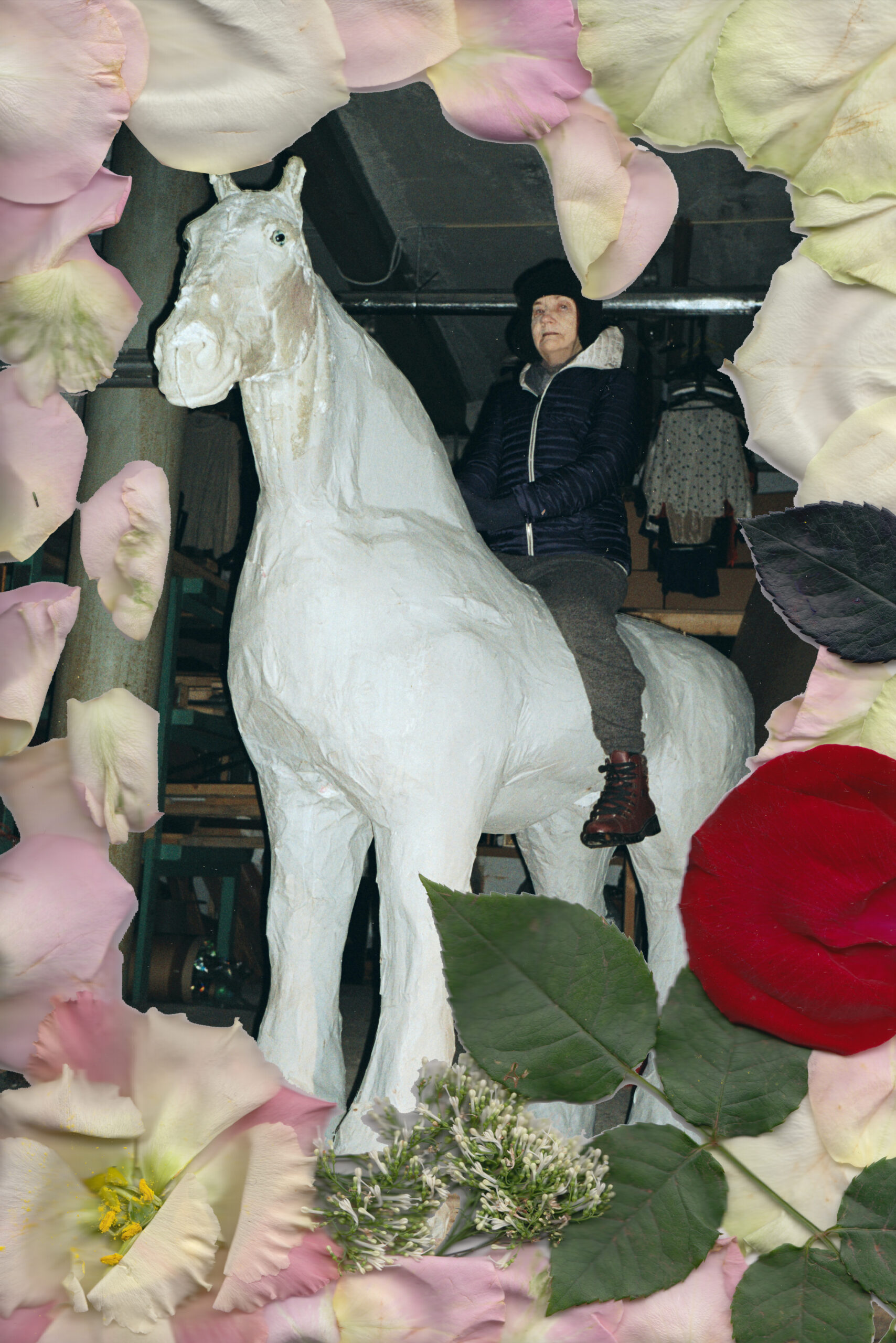

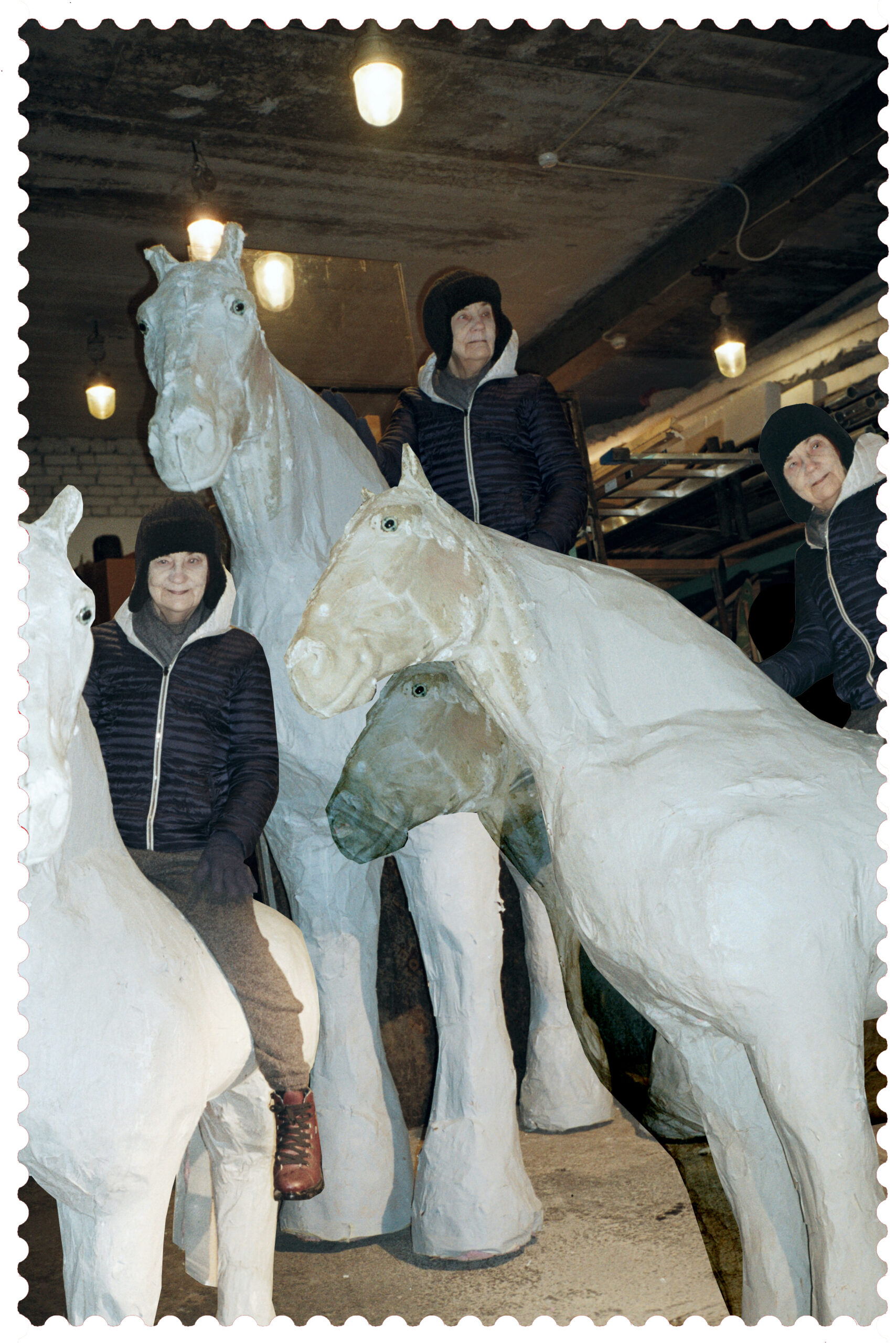

Although at the forefront of changes in contemporary art, Komissarov has always worked with historical material as well, putting it into a contemporary perspective. Passionately, tirelessly and without compromise, she has followed the enormous social changes of the last 50 years, always critically addressing these through means of visual culture and her curatorial practice. Komissarov has always attempted to place the local heritage and processes in a wider context, to relate it to changes taking place internationally. Together with Maria Arusoo and Eda Tuulberg, she is working on a curatorial project titled Through the Black Gorge of Your Eyes, which offers a contemporary perspective on the work of Estonian women printmakers in the 1960s and 1980s and invites contemporary performance artists to enter into a dialogue with the themes highlighted by the printmakers of the Soviet era.

Maria Arusoo: Could you describe what the art field was like when you were at university and after graduating in the early 1970s?

Eha Komissarov: At the time, art was very exciting. The Estonian art field was striving towards freedom and trying to find its place in Europe. It was trying to find a way to wriggle away from Russian influence. When it came to culture, there were two main cities – Tartu and Tallinn. I went to the University of Tartu and at the time, Tartu was valued because artists were trying to revive the painting tradition of the Pallas Higher Arts School that had existed before the Soviet occupation. In Tallinn, however, tradition took a backseat, and they were trying to invent something new. I also remember that there was a ferry line

MA: How did you come to art, what decisions led you to that?

EK: It was a pure coincidence. When I was a student (late 1960s and early 1970s) the trajectory of possibilities for studying was very clearly defined. I was fascinated by history, but that was also a time when parts of history were banned and you could only use certain keywords to talk about things. There were many themes that were never touched upon when it came to the post-war period. Not that they were always necessarily forbidden but you needed permission to work in the archive and common people were not given access. Art history was taught as a minor and I liked it a lot.

Eda Tuulberg: What inspired you the most in culture at the time?

EK: Personally, I was the most fascinated by pop culture and all the changes it was going through – the new language and how a new vocabulary and code appeared in culture, society and people’s behaviour. I loved that certain borders were dissolved. Soviet society was so institutional. But suddenly, all the young professors began addressing the students in a more casual way and even the rector of the university could be spoken to less formally. The change of code in behaviour was so exciting and so different from everything that had come before. To be honest, it was thrilling to see all the old values go to hell.

MA: What was your relationship to the programmatic Soviet emancipation that brandished equality of women and men?

EK: In society, most things were decided by men who were often remarkably dumber and more limited than the women for whom they made decisions. I became more consciously aware of that in the early 1970s. It was very easy for me to relate to traditional feminism when I looked at the choices available to women in Estonian society. Soviet society was a welfare society in the sense that nobody could get rich but also nobody starved, unless you suffered from direct repressions by the state, of course. The social transition of the 1990s in Estonia also presented a lot of people with tough choices. I was shocked to see children beg on the streets in groups and how prostitution became very clearly visible. I had no illusions about capitalism. I knew people were going to be out of jobs. And I knew competing would become the norm. That much I had understood as an observer. And so, I found some support in feminist ideas that helped me to address and make sense of all the social changes.

MA: In Estonia, you are known as someone who tirelessly introduces and advocates for contemporary art. What was initially so fascinating about contemporary art for you?

EK: I was interested in contemporary art because it was extremely difficult to get access to it during the Soviet period... Thinking of the Estonian art field at the time – you definitely had to know an artist personally to even see that kind of art. As a person, I am kind of an unorganised character. I really loved the post-war international art history. I truly loved abstract art, which was forbidden in the Soviet Union because of the Cold War. You could only see very little. At some point, dictionaries of art published in Germany became available in Estonia as well and many significant names of contemporary artists were included. Sometimes, we could get our hands on these, they cost next to nothing. The more hidden a culture, the more people are drawn to it. When everything is spoon-fed, it's less effective. That's what Finnish artists always said when they visited Estonia. They claimed that a society can't have too much freedom, it always needs some kind of resistance. Citizens must feel that they need to fight and resist through their art, that gives a new meaning to the work. I didn't like that – it felt like since Finland was free, it was easy for them to come here and discuss how we needed to suffer and be a little repressed. When I confronted them about this, they replied that no-no, it's just good for any culture to have a bit of conflict and pressure.

ET: When you started working at the museum, you had to work with historic material; however, as a critic you wrote about contemporary developments in art as well. How did you manage these roles? Did you feel there was a conflict between them? It seems you were almost like a chameleon.

EK: I mean, a true Soviet citizen always had many roles. Party member, executive employee, a career person, a nationalist crying under the Christmas tree.

MA: Did you feel you could realise your ambitions within that system?

EK: I didn't really think about my ambitions, I was more working on developing myself. I realised I didn't know anything, so I read a lot. Thanks to the samizdat

MA: On the one hand, you seem to be extremely curious. You read and swallow large amounts of information, you keenly observe the world around you, you are knowledgeable and sensitive and easily pick things up. Yet, even in your early 20s you never fell under the spell of gurus, as it sometimes happens to people.

EK: My ideal was always anarchism at the time. Often people do not intend to become gurus – they just have a message to spread and people start gathering around them. Some of the local art gurus radiated a completely new kind of thinking, things I had never even dreamt of. I wasn't working with any super exciting esoteric teachings or life changing issues because as an anarchist and democrat, I think that every person has to find themselves based on their own experiences. To an extent it's also about fate. I have seen people who have a terrible fate, who die precisely when it would be so important for them to live.

ET: It's quite interesting that you consider yourself an anarchist but at the same time you've worked in a museum for 50 years. Has this been a pragmatic decision or is there something in the institution of the museum you strongly believe in?

EK: I had a certain interest, a purely creative interest in the museum. When you work intensely and seriously with contemporary art, you will gain a new perspective on art history. Especially when it came to our local history, where everything was so restrained and adorned with myths of the spirit of Parisian art. I did not care about any of these myths. I was the generation who thought: "Paris is dead, long live New York!" I had been to Paris but not New York. It’s really easy to make decisions like that! But I knew that I had a completely new perspective on art history, and I wanted to put it to work.

ET: When did that become possible for you?

EK: In the mid-1990s, when decisions about the new building for the Art Museum of Estonia (now Kumu – Ed.) began, this is when I started to think about it.

ET: How do you see the role of museums today? Or the role of museum curators?

EK: I like what the Estonian philosopher Eik Herman said about museums: museums are filled with collections, but now a time has come, where these collections need to prove their right to exist in a new, contemporary culture. I have always had an ambivalent role. I have always championed the new and at the same time, in the museum, I am personally involved with many collections – I have helped to establish them, I have made recommendations and acquired works. And now I suddenly have to be the defender of these shabby collections – at the onslaught of art that is being made in increasingly better conditions. Maybe I'm stepping into inappropriate territory here, but Herman's idea really spoke to me. And when Covid came, so many of our exhibitions were postponed, which meant we needed to take a closer look again at the works we already had in the museum. So, we once again discovered that we have so much art, yet only a tiny portion of that circles in the public and most of it remains uninterpreted in the context of contemporary culture. We have abandoned it, left it to just sit there.

MA: Talking about the upheaval and the arrival of contemporary art in Estonia in the 1990s, how much do you see yourself responsible for that? Here, you had the choice to either start copying the West or to blend it with our own tradition and create a new model.

EK: In order to blend things you need the other half.

MA: How consciously did you participate in this?

EK: I participated in a very radical manner, I felt that it was the time to cut the umbilical cord, take a strong turn and find a new focus, new energy, to be able to have a dialogue with the current moment. I brought artists to Estonia, who were doing important work at the time and also selected the more independent Estonian artists. Estonian art took a long time to get used to independence. It was as if everyone was always waiting to be told what to do. And finally it happened – the whole Soros system in the 1990s. I have read extremely critical opinions that the network of Soros centres was a network of Western colonialism, based on an imperialist idea. I don't quite agree. Estonia is a stronghold of its national culture, we stick together. The idea that people need to work together and support each other is really good in practice and there have been times, like the Art Nouveau period, for example, where art favoured these little groupings. But when the idea of national culture was thrown out, everything became very dramatic. Estonian artists didn't really go along with the idea that they needed to push everything they had known aside and suddenly start deconstructing art.

ET: Do you agree that in this case the baby was thrown out with bathwater – certain people and phenomena were pushed aside? In some ways the exhibition of women printmakers we are working on now sets out to revise women printmakers as a phenomenon in Soviet art history. In the 1990s, they, too, were overshadowed by all the new developments in contemporary art.

EK: In the past, there have been periods, where these artists have been highlighted and valued. For example, this has to do with how Estonian art silently resisted Soviet Socialist Realism. I'm probably romanticising my youth, but I consider this a great achievement and I am truly sorry that our culture can no longer read these codes. In the 1990s, artists were suddenly all like, "Oh, sure, some art was made in the past but THEN I ARRIVED and showed everyone my ass! I screamed, broke stuff, ran around! Look what I did!" I was always against all such extremities. Everyone like this was given a platform. The wilder you were, the better it was. In the 90s, I did think about how to approach the work of women printmakers in a contemporary context. I knew these artists; they had had a massive influence on my professional development as well. I was wondering how to save them. And then I realised it was they who needed to take the first step and break out of their system. But they almost never did. What I mean by this – you step outside of your conventional modus operandi and try to approach the world in a completely new way.

MA: But do you not think this also depends on a person's character? There are artists who reinvent their work each decade, they go along with the changing times and then there are artists who keep with their idiosyncratic line of work, while times around them change and at some point their ideas become relevant again. Why was it important for you to return to the works of women printmakers of the Soviet period now, at this particular moment in time?

EK: Absolutely. I love how during the period Kumu Art Museum was under construction, internet radicals were discussing how museums are a relic, everything needs to be put online and there is no need for expensive buildings. To that my colleague of many years, art historian Mai Levin very cleverly said: "Well, life has shown that in a museum, none of the artworks in collections are pointless and useless. Time moves forward and there is something for each new era, the ‘pointless’ work becomes relevant again. And everyone admires it." So that is the phenomenon of the museum.

I think it is not too late for these women printmakers, as their work highlights certain keywords that are still very much alive in Estonian historical memory, that can still touch people. For example, the pursuit of aesthetic harmony, search for female expression, the need to create symbols, goodness, empathy, ideas like that. I would like to interpret these in such a way that young people today, who are so removed from the time these works were created and who are not interested in creating specifically Estonian art, would understand that this is what our art history is like, that these are the works that were created during difficult times. There were women who came and wanted to do something, and they did it! I want to interpret these works in a way that they would start making sense in a contemporary context again.

MA: You are a very hands-on curator. Whenever I think about you and the exhibitions you have curated, I remember you in dusty clothes putting finishing touches on things, putting up labels for artworks etc.

EK: Well, in the 1990s, we didn't have cleaners at Soolaladu, the contemporary art space of the Art Museum of Estonia. Can you imagine? We had to install whole exhibitions but the cleaner only came on the day of the opening. So, I often stayed there until 3 am. When we were done with installing, we needed to clean up the sawdust. We didn't have a vacuum cleaner either. I used brooms to sweep the space. And only then I could go home because I couldn't leave a mess for the next day, everything needed to be clean. Such were the conditions.

ET: What are curators' options and obligations at a time where public intellectual space is increasingly hijacked by right-wing conservatives, the climate crisis, Russia's horrific actions in Ukraine, and Covid also still lurking in the background?

EK: Fight as much as you have strength for, but tackle these issues one at a time. And when you run out of steam, think of something else. But I think that the combination of all of these factors will lead to the rise of national narratives. In relation to the war in Ukraine in particular. Not because the conservative right decided so. I see signs that a certain kind of romantic spirit is being revived. Cynicism has run its course, it is depleted, there is nowhere else to go from here. Empathy will be more valued again and I don't think this means focusing on the situation of nations in a narrow sense but there will be another, wider perspective on the whole world. I would like to hope so. For something more empathic.