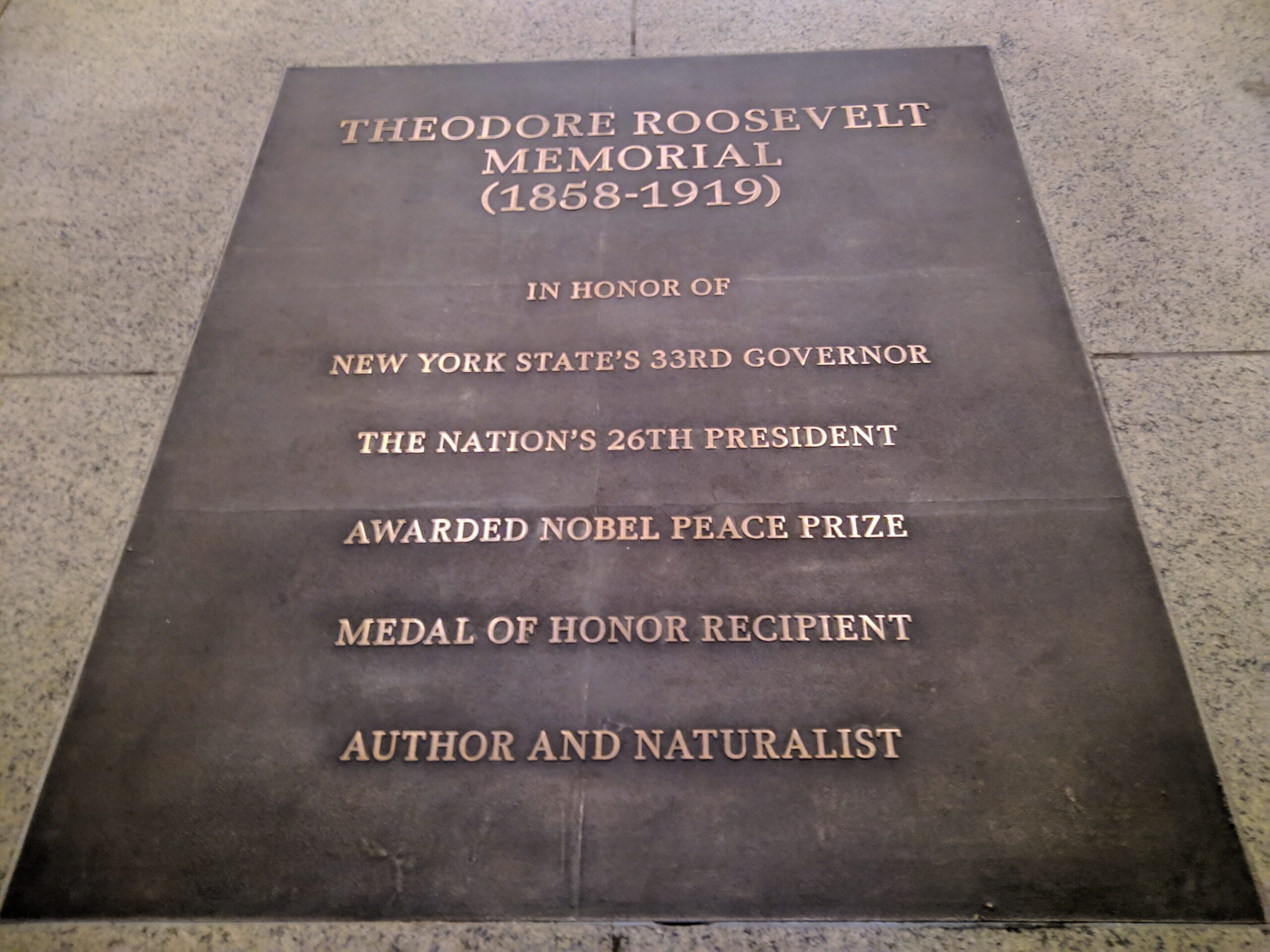

Western observers may have experienced the latest iteration of the monument wars in the Baltics with some cognitive dissonance. In the anglophone world, popular movements such as Black Lives Matter have demanded the decolonisation of public spaces. The British coloniser Cecil Rhodes, confederate general Robert E. Lee, even Theodore Roosevelt are no longer welcome in polite company. Owing to public pressure, universities have renamed buildings, and museums have been recontextualising their collections.

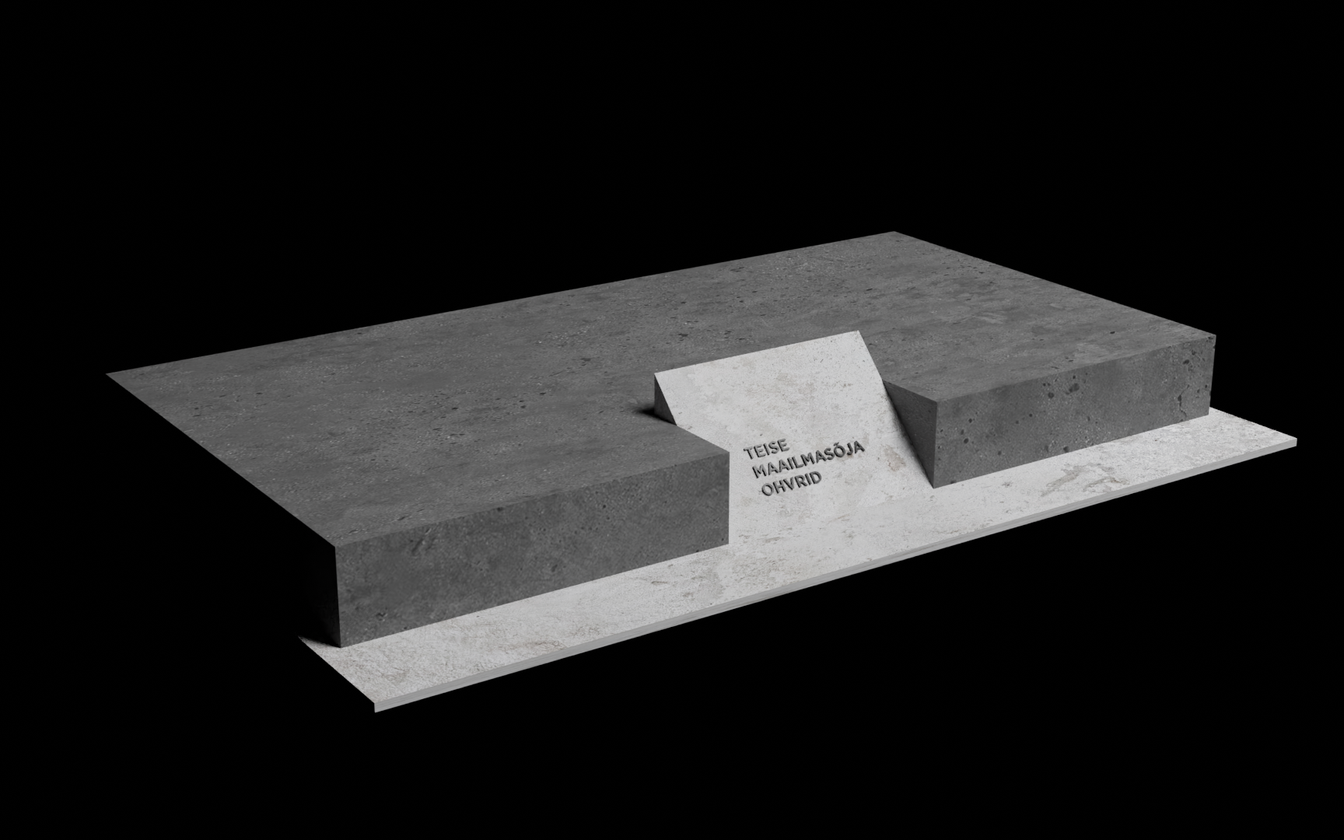

Monuments are also falling in the Baltics, spurred by the war in Ukraine and responding to Vladimir Putin’s propagandistic use of the past to justify his invasion. Last year, Latvian authorities dismantled a massive World War II memorial in the capital Riga, where ethnic Russians had been gathering every year on 9 May to commemorate the end of the war. In Estonia, the government removed a Soviet tank memorial from the border town of Narva, citing security concerns. All three Baltic countries have passed laws mandating the removal of Soviet war memorials, war graves and occupation-era symbols from buildings.

Yet these decisions have been met with strong public opposition, particularly from historians, art historians and conservators. If the removal of confederate and colonialist statues in the West has been interpreted as a democratisation of public space and an exorcism of the legacy of white supremacy, then in the Baltics, critics of the monument wars have called the dismantling of Soviet memorials undemocratic. By forming secret committees, working according to an accelerated schedule, and refusing to respond to critics, art historian Linda Kaljundi argues that Baltic governments are silencing public debate – “the worst approach, given the emotional intensity and polarising nature of the issue”. Instead she suggests cultivating a pedagogical approach to Soviet era monuments, to use them to “work through” difficult historical periods, and “to understand how different communities can and do have different interpretations of the past”.

Indeed, although the term “decolonisation” is also invoked here, the monument wars in the Baltics differ from their Western counterparts in several key respects. First, they are only the latest wave in a process that goes back to the 1990s. Statues of Lenin, Stalin, and local communist leaders might be found in Lithuania’s Grūto parkas or in Estonia’s Vabamu museum, but not on public squares because they were taken down in the early 1990s, when the Baltics regained their independence. The current wave of dismantling is therefore not oriented towards hot and controversial symbols of the occupation period, but towards smaller war memorials and graves that have often been forgotten, or architectural details, such as murals or hammer-and-sickle symbols on the facades of buildings such as Tallinn’s Sõprus cinema.

Second, the list of targeted monuments is much more extensive than in the US or the UK. In Estonia, a government study from 2022 listed a total of 322 Soviet monuments still remaining in the country and ruled that 244 of them should be removed. This included 133 war graves, which require reburials. For comparison, a Southern Poverty Law Center study from 2020 found that 168 Confederate symbols had been removed in the US with more than 2,100 remaining. In the Baltics, the loss of pedagogical potential in the built environment is a real danger, while in the US, the situation is quite the opposite: symbols with colonialist or white supremacist history tend to dominate public spaces, overwhelming an admittedly increasing number of monuments that celebrate Black and Indigenous culture.

Third, the role these remaining Soviet monuments play in the contemporary Baltic context is also quite different. We should recall that the movement to remove Confederate statues in the US did not spring from nowhere, rather, they were responding to an upsurge of white supremacist violence, notably the Charleston church shooting in 2015 and the Unite the Right rally of 2017. Indeed, as the American Historical Association noted in its statement at the time, most Confederate statues were never put up as memorials to the Civil War, but instead were erected decades later, at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, and were explicitly designed to intimidate Black Americans during the period of post-Reconstruction backlash.

The legacy of the remaining Soviet monuments is complicated in a different way. On the one hand, Putin’s regime is clearly using the narrative of the Great Patriotic War to drum up support for the war in Ukraine, an ‘anti-fascist’ operation, as Russia would have it. On the other hand, many of the monuments in question are active as war memorials for the Russian minority population, who gather there to commemorate fallen family members, celebrate the end of the war on 9 May, or take pictures during family events, such as weddings.

Critics have pointed out that machines of destruction in public spaces create unsavoury associations in an era of Russian aggression. Yet, using tanks as war memorials, as was the case in Narva, is by no means an uncommon practice. Memorials of British Churchill and US Sherman tanks are found all over the coastline of Normandy, and Soviet tank memorials are not uncommon (nor uncontroversial) in East Germany or Poland. Other memorials are complicated by the fact that they have been designed by local architects and sculptors, and have, over time, lost their association with the Soviet period. The expansive complex at Maarjamäe in Tallinn, for instance, is more likely to be identified as one location used for shooting the film Tenet than a Soviet memorial to World War II. In any case, the memory politics of the Baltic memorials resist a single interpretation.

Finally, while the removal of statues of Soviet leaders in 1991 enjoyed broad popular support, it is not clear that there is a large constituency that is actively bothered by the remaining monuments today. Indeed, public opinion polls show either indifference or support for the monuments. In Estonia, 43% of Estonian speaking respondents said that Soviet era monuments “had no meaning for them”, while 16% said they evoke “negative feelings and memories”. Often, local communities have voiced support for the monuments. The removal of the T-34 tank in the predominantly Russian-speaking town of Narva was accompanied by peaceful gatherings. A Soviet war memorial, Kivi-Jüri, in the Estonian island town of Kärdla, was taken to a military museum, even as local leaders called for caution and debate.

By and large, the campaign to remove Soviet symbols has been led by conservative politicians, who are not unfairly accused of drumming up nationalism in advance of the election season. Rather than being powered by grassroots initiatives, like the anticolonial and antislavery campaigns in the US and the UK, the monument removals in the Baltics are organised by the central government, often cloaked in secrecy. In Estonia, the list of Soviet monuments to be dismantled was drawn up by a secret committee, and the government was given the right, in spite of protests by various professional societies, to overrule the decisions of local municipalities and heritage boards.

The removals are now underway, having drawn more attention to the monuments than if they had been simply left alone. The monument wars have been discussed at academic conferences and on TV talk shows, and have certainly offered many ‘pedagogical opportunities’ for discussing the intersection of politics, memory and history. It remains to be seen if the loss of material heritage has been worth the payoff.