Language plays an important role in framing visual art, presenting it as part of a historical narrative but also in creating new narratives. We can clearly see this at the current permanent exhibition Landscapes of Identity at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn, so we asked Kadi Polli, the director of the museum and one of the curators of the permanent display about the role of language in working with historical materials.

Landscapes of Identity focuses on art created by various communities in Estonia (Russian, Estonian, Baltic-German) and the entanglements these entail. However, these communities have very different linguistic traditions – what challenges did this pose for the museum in curating the exhibition?

With Landscapes of Identity we did indeed want to show the entanglements between the Baltic-German, Russian and Estonian cultures instead of focusing on difference. German, Russian and Estonian have historically been the most prominent languages in Estonia and a large part of the Estonian cultural elite spoke all three. The same can be said about the imagery – there are a lot of similarities and transference of motifs. It is easy to see that many of the symbolic images in Estonian art – be it a girl in national dress, seaside views with glacial boulders or landscapes with village roads and heavy skies – are modelled after the 19th-century Russian salon painting or the landscapes created by the Düsseldorf school of painting.

When it comes to the texts in the exhibition spaces more specifically, we decided in the beginning that we would use the three languages that are significant in Estonian culture, and add English as well. So, the exhibition speaks about Estonian art in four languages. This was a conceptual decision also when it comes to the introductory video, in which we hear German (Ulrike Plath), Russian (David Vseviov), Estonian (Krista Kodres) and English (Andres Kasekamp, Bart Pushaw). For the video, we chose people with different linguistic backgrounds, who all look at Estonian art and culture from the perspective of different communities, are familiar with both the national narrative and international context and are able to speak to an international audience. The exhibition texts are created with the same agenda in mind. Together with Linda Kaljundi we wanted the exhibition texts in different languages not to be exact translations of the same text but to consider the reader and provide a wider context to local terms, if necessary.

Language is, especially in Estonian culture, at the foundation of national identity – how can language be used in a way that different identities and voices could also be given enough space? What are some of the ways a contemporary museum can communicate the linguistic layers that accumulate in artworks and other artefacts during their lifetime, considering the fact that the life span of these objects is often much longer than that of people?

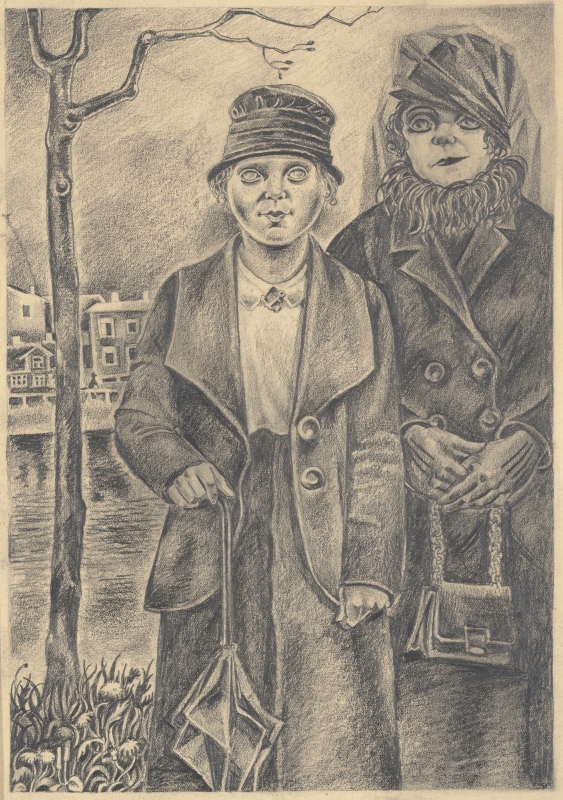

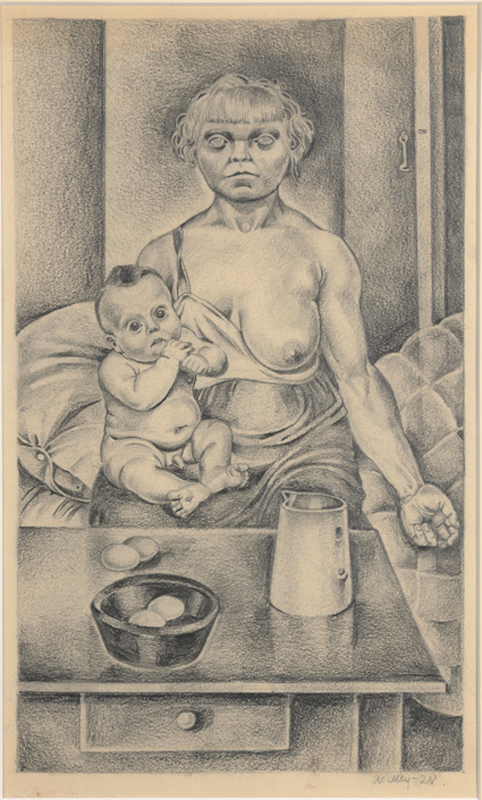

For us, giving a voice to different communities did not only mean approaching these based on language or nationality. Although these were also a factor, for example, we highlighted the presence of Baltic-German and Russian artists in the art created during the Estonian Republic at the beginning of the 20th century. But it was equally important to give visibility to women artists and those of a different class or race. It is not unimportant in Estonian art history that women artists have notably featured more marginalised people; for example, Natalie Mei has created profound drawings looking at single mothers and prostitution.

When working with art from earlier periods, we inevitably came across those linguistic layers that were exposed in earlier descriptions and titles of artworks. This is a whole other discussion that leads to the recognition that the titles of artworks are an important part of art history. Updating these is, in fact, the task of art and memory institutions, be it done due to new research and discoveries or the changing meanings of language and terms over time.