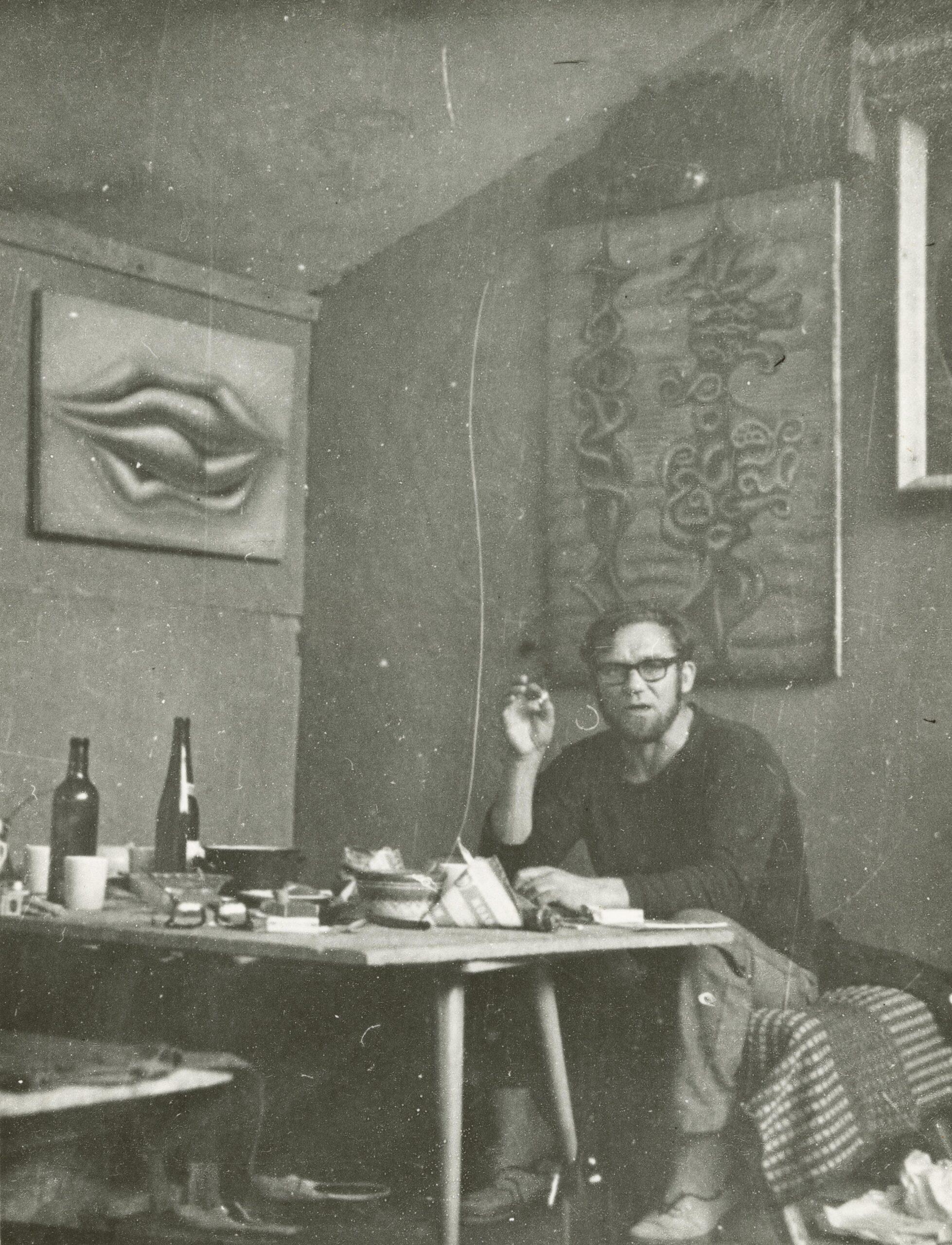

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970) is one of the key figures in Estonian art of the second half of the 20th century. His charismatic personality, rich and multifaceted artistic heritage – working in-depth with surreal and abstract imageries to outline some of his main interests – as well as novel-worthy biography with such milestones as political imprisonment, great love, life outside his homeland and early death, makes him a true legend. Belonging both in the history of post-WWII Estonian modernism and the non-official Moscow art of the 1950s and 1960s that sprouted Moscow conceptualism, Sooster’s case needs revision especially nowadays, when the critique of colonial aspects of Soviet art history is an important agenda.

Born and raised on a farm on the Estonian island of Hiiumaa, Sooster studied at the Higher Art School Pallas (from 1944 the Estonian SSR Tartu Art State Institute) from 1943 to 1949. He therefore inherited the values of the first decades of the Republic of Estonia – connection to the traditional culture, a bond with nature and agriculture, and, though already fading under Sovietisation, dialogue with modernism and developing an original art and visual culture relevant for a young European country of the time. In the 1940s, the Tartu school of painting was cultivating modest late impressionism, and trying to adjust, however rather formally, to the canons of Socialist Realism, but students still had access to books and journals on modern art, both in public and private collections. In this context, Sooster was still able to study the history of more radical 20th century art through books, becoming acquainted with the work of cubists or surrealists already as a student. This, as well as the vivid intellectual life and French-oriented café culture in the university city of Tartu, undoubtedly formed a particular way of thinking, which created the basis for his later art practice.

Unfortunately, Sooster did not have much chance to develop his artistic ideas and career after graduating. Soon after moving from Tallinn in search of a job, he and a group of co-students and friends from Tartu were accused of anti-Soviet activities, so he spent the years 1949–1955 in labour camps in Kazakhstan.

Therefore, Sooster’s participation in official exhibitions during his lifetime was rather the exception and his works were known to a relatively small though highly professional audience. Still, his influence on other artists is considered essential: for instance, one of the leaders of Moscow conceptualism and the later international art star Ilya Kabakov has referred to Sooster as his teacher. Kabakov also organised their joint exhibition in the UK in 1992

However, this dynamic did not develop only in the direction of Moscow. Sooster visited his circle of friends in Tartu too, discussing art and creative methods, and the exchange of ideas was mutual. In addition, Sooster organised meetings between the Tartu circle and the members of the ANK group, facilitating communication between different generations and groups of innovative artists in Estonia. Artists from Moscow also came to Estonia to see the most radical works by artists in Tartu and Tallinn in their studios, but to also enjoy what was felt to be the Soviet “West”, where the official cultural life was more liberal and, due to proximity to Finland, more informed about contemporary developments outside the Soviet Union. Therefore, a cultural bridge between Moscow and Estonia was established and this cultural exchange continued even after Sooster’s death, into the 1970s and 1980s, fading only after the collapse of the USSR. After gaining independence, each nation was preoccupied with the construction of its own new identity as well as establishing contacts with the rest of the world, previously hidden behind the Iron Curtain.

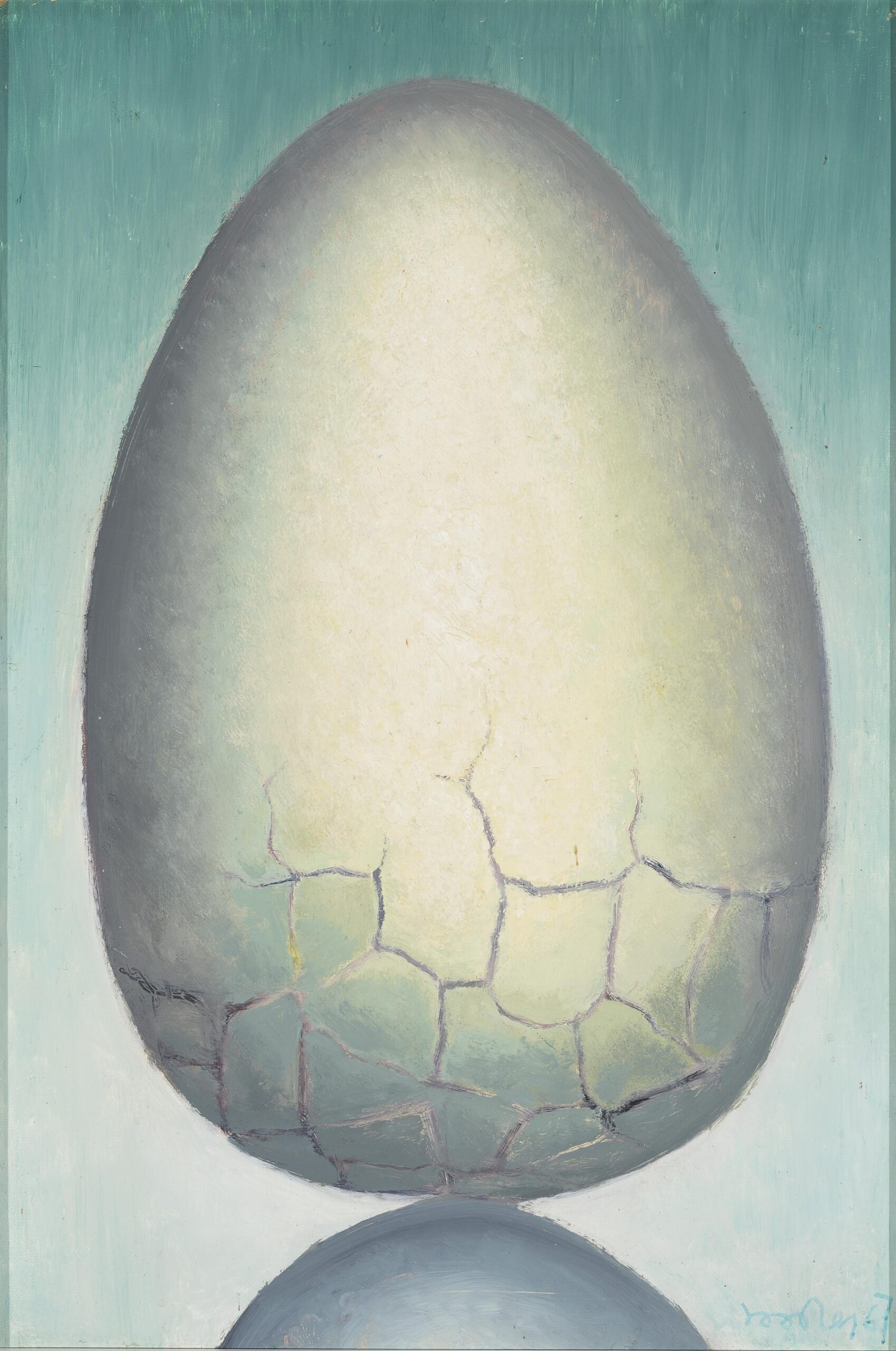

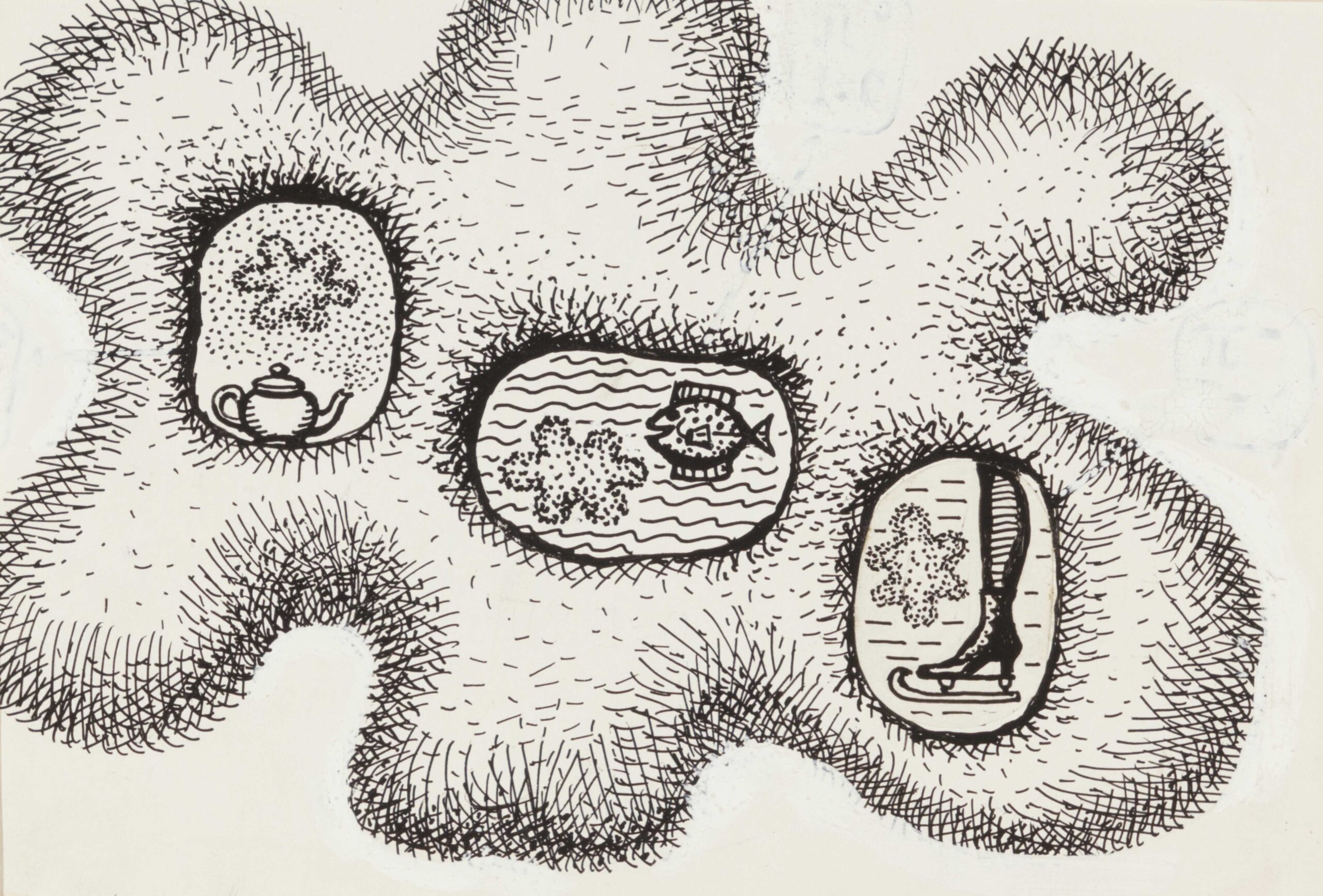

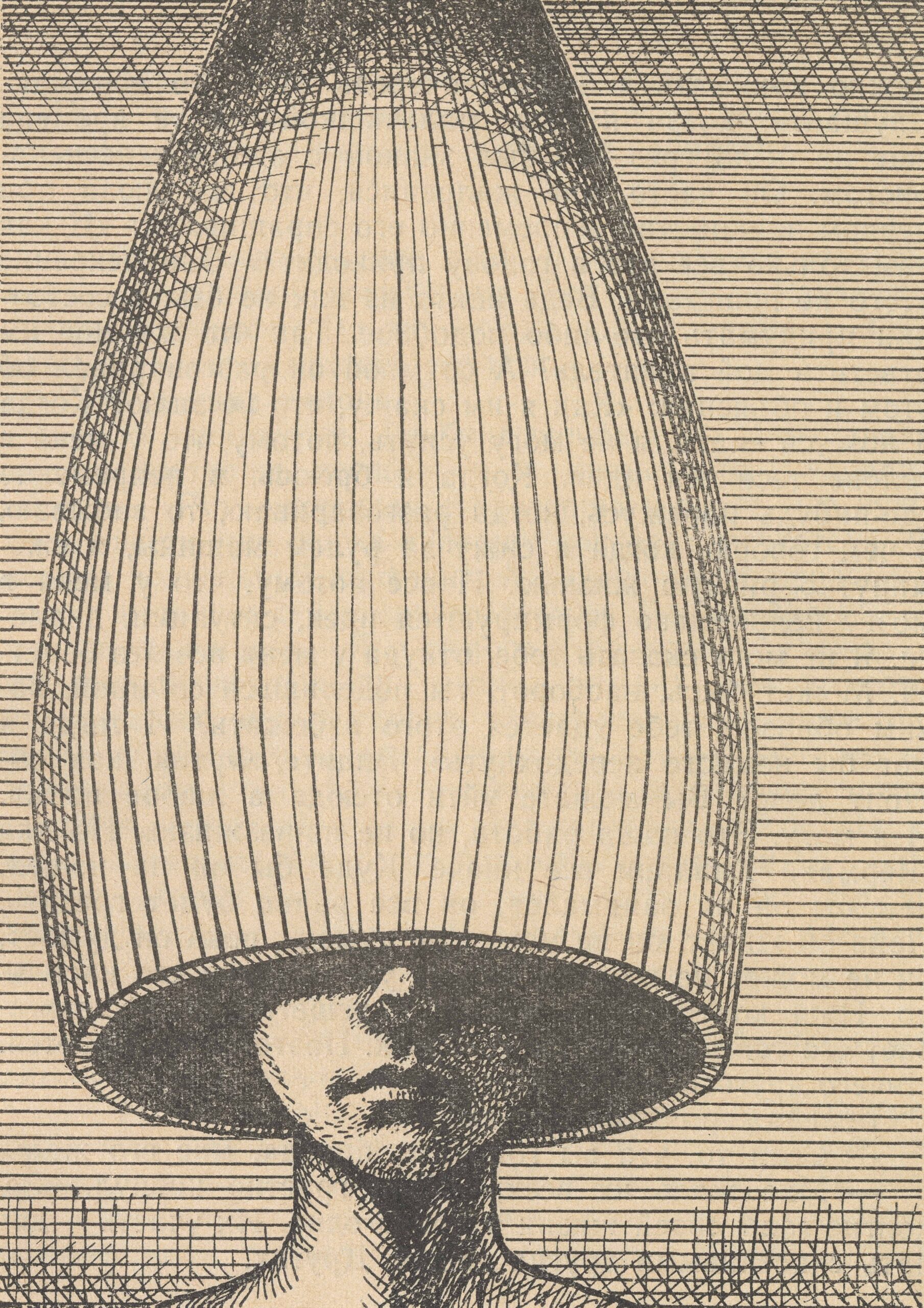

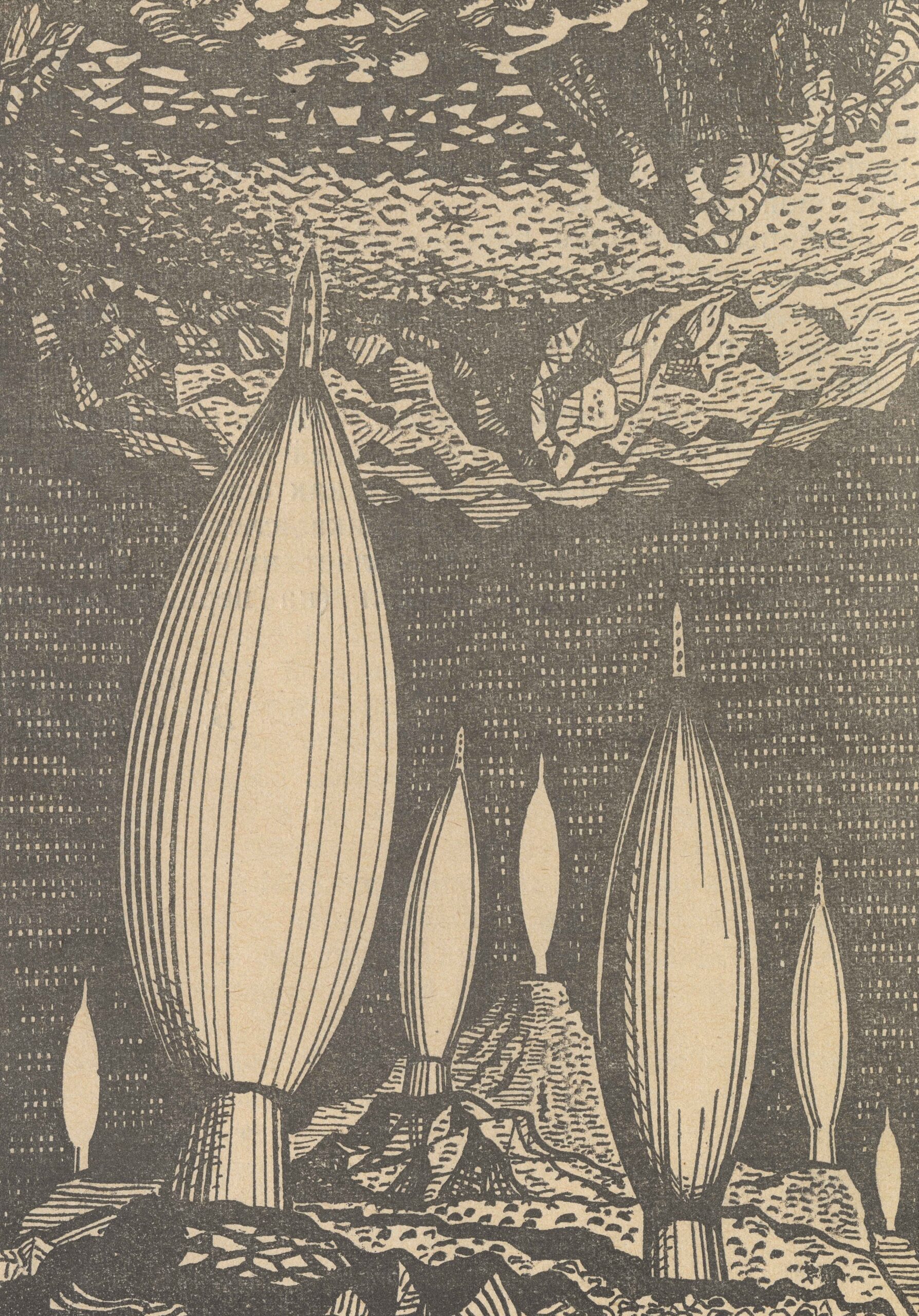

Therefore, Sooster had a multiple or hybrid identity – a kind of trickster, who was everywhere but fully belonged nowhere. In Moscow, he was perceived as a foreigner because of his accent and habits, such as smoking a pipe and sketching in a café. However, when it comes to Estonia, he might have felt it was too provincial, although he did miss his homeland and it was the inspiration for his cryptic world of symbols, which included the fish, the sea, the egg and the juniper. Sooster’s identity as an artist was also hybrid because he did not focus on one aesthetic-philosophical system but simultaneously worked with very different visual and conceptual approaches – from the absurd of surrealism to the estrangement of metaphysical painting, from the deformation of cubism to the expressiveness or constructed analytical nature of abstractionism. In Moscow, with his close friend and colleague Yuri Sobolev, Sooster continued his research of modern art – not only playing with many of its methods in his work

Sooster’s hybridity extends to the artistic media he worked in; for example, book illustration was not only his main way of earning a living, but also, to a degree, a platform for experimenting with new ideas. Unlike his paintings and drawings, books illustrated by him enjoyed a much wider audience during his lifetime, as Soviet publishing culture included enormous print runs. Good examples are Sooster’s illustrations for popular science books and articles,

It is essential to retell stories; however, in the context of art history, it is also important not only to remember the initial narrative but to also revise it according to newer knowledge. Today, it is important to acknowledge Ülo Sooster as an artist of multiple identities and multiple mutual influences, which also define his uniqueness. While Sooster’s artistic dialogue and field of influence in the Estonian context has been researched rather extensively, its Moscow counterpart still needs comprehensive research, as it tackles questions of the Russian-centred discourse of Soviet art. Being simultaneously acknowledged and at times half-forgotten cornerstone to many important processes in the art of his time, and not only in the Soviet context, Sooster definitely deserves greater international attention.