In-between systems and services

Outsider art or art brut in Estonia has not been researched much until recent years. As an object of research, outsider art is closely linked to developments in the fields of psychiatry and special care services and in the wider society – in Estonia, attitudes towards people with psychological special needs (mental disability, psychiatric diagnoses) have only recently started changing for the better. We have very little knowledge about older, that is, historical art created by people with special mental health needs, and we know almost nothing about such artworks made between 1920 and 1990. In the current state of research, we lack facts, so we can only make educated guesses when it comes to outsider art from the past. Estonian psychiatric hospitals, such as the clinic in Tartu (established in 1877), Jämejala near Viljandi (1897), Seewald in Tallinn (1903) and Pilguse in Saaremaa (1913), all simultaneously functioned both as medical institutions and care facilities until World War II. According to the Central Bureau of the Republic of Estonia in 1929, care was provided to around 3,000 mentally ill people. During the Soviet occupation, people with special mental health needs were increasingly institutionalised and the number of both people in special care and the number of care homes (or as they were called at the time, homes for invalids) increased. The political agenda of Soviet period care facilities was tied to ideas of re-education through labour (for people for whom such an approach was applicable)

After the Soviet occupation, especially from the 2000s onwards, social services were restructured and since then, one of the main objectives in special care has been deinstitutionalisation.

Establishing a centre

In 2003, I started working as the director of the Kondas Centre, an art museum that had just opened in Viljandi. The permanent exhibition presents the works of the naïve painter Paul Kondas (1900–1985), a school teacher from Viljandi and Suure-Jaani. As he was also a self-taught artist, the centre's mission is to research and introduce phenomena that often remain outside the established art world, such as self-taught and naïve artists and Sunday painters. A year after the museum was opened, I started going on research trips around Estonia to find artists who had a high drive to create art but modest knowledge and skill compared to professionals. Many of the original artists I met during the fieldwork between 2004 and 2008, were already elderly, and by now, almost all of them have left this world. Interviewing them, I found that these artists had mostly held simple jobs, lived in small towns and villages away from large centres and had had extremely limited contact with professional cultural fields. After a more active period of researching the legacy of naïve artists, my focus shifted towards art created by people with special mental health needs. The first exhibitions of works by artists in need of additional support

The first challenge we faced when starting the project as part of the One Hundred Art Landscapes programme was to find information about artists and how to reach them both in institutions and homes. How many could there even be in Estonia? We had many questions and not so many answers.

According to studies, there are up to 55,000 people with special mental health needs living in Estonia. That is as many as there are inhabitants in Narva, the third-largest city in Estonia. About 11,000 people receive either permanent or temporary care services, but in offering creative services to people in special care, we are lagging behind Western Europe by 20 to 30 years.

As a first step, I turned to the list of special care facilities provided on the web page of the Social Insurance Board and began visiting these. Although these institutions are not generally very open, buzzwords like the "centenary art programme" and "art exhibition" opened doors to many support and day care centres. These visits allowed us to meet people creating art in the facilities, as well as the conditions and opportunities for crafting and making art on site but more broadly also how the system of special care operates. Sometimes differences of opinion appeared and it became clear we had a different understanding of what art is – in the facilities the personnel rarely thought that the people who live there make ‘art’, but rather they ‘draw things’. I witnessed how artworks made during the day were binned in the evening because "they will make new ones" the following day. Notably, weaving looms were present in almost all of the facilities – as a relic of the Soviet period attitude that the patents need to work, I assume – but high-quality paper, pencils and paint were much harder to find.

Before spring 2020, when care facilities were almost entirely closed due to the pandemic, I managed to visit around 25 special care facilities across the country – from Võru to Saaremaa and Pärnu to Narva. By early 2023, the Kondas centre had bought over 500 artworks thanks to the support of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia and collected valuable material, interviewed artists as well as activities supervisors. The primary criterium for purchase was the level of artistry and in some cases, the remarkable story behind the piece.

Artists’ stories

On several occasions, these trips made me wonder about the source of creativity. For example, sometimes art is the only means of communication with the world, as was the case with Ingrid, a woman whose colourful images of communication are now part of the Kondas collection. Ingrid (b. 1952) is deaf and mute and lives in a care home in Sillamäe in Ida-Viru County, located in a hospital complex in the former closed Soviet city. Ingrid is mentally disabled and nobody ever taught her sign language, yet she started using drawing to communicate: whenever she needs something or has run out of something – hand cream, toilet paper, soap, clean clothes – she draws it on paper and brings it to a carer at her facility. Thanks to a volunteer from Sweden who worked at the care home years ago, Ingrid has been provided with high quality art supplies. In her case, making art is not just a practical need but also a way to express thoughts and feelings. An attentive observer, she depicts events around her; often she seems to mentally divide the surface of the paper in two, depicting two seemingly unrelated themes. Ingrid relieves stress and tension by drawing colourful squares in her notebook.

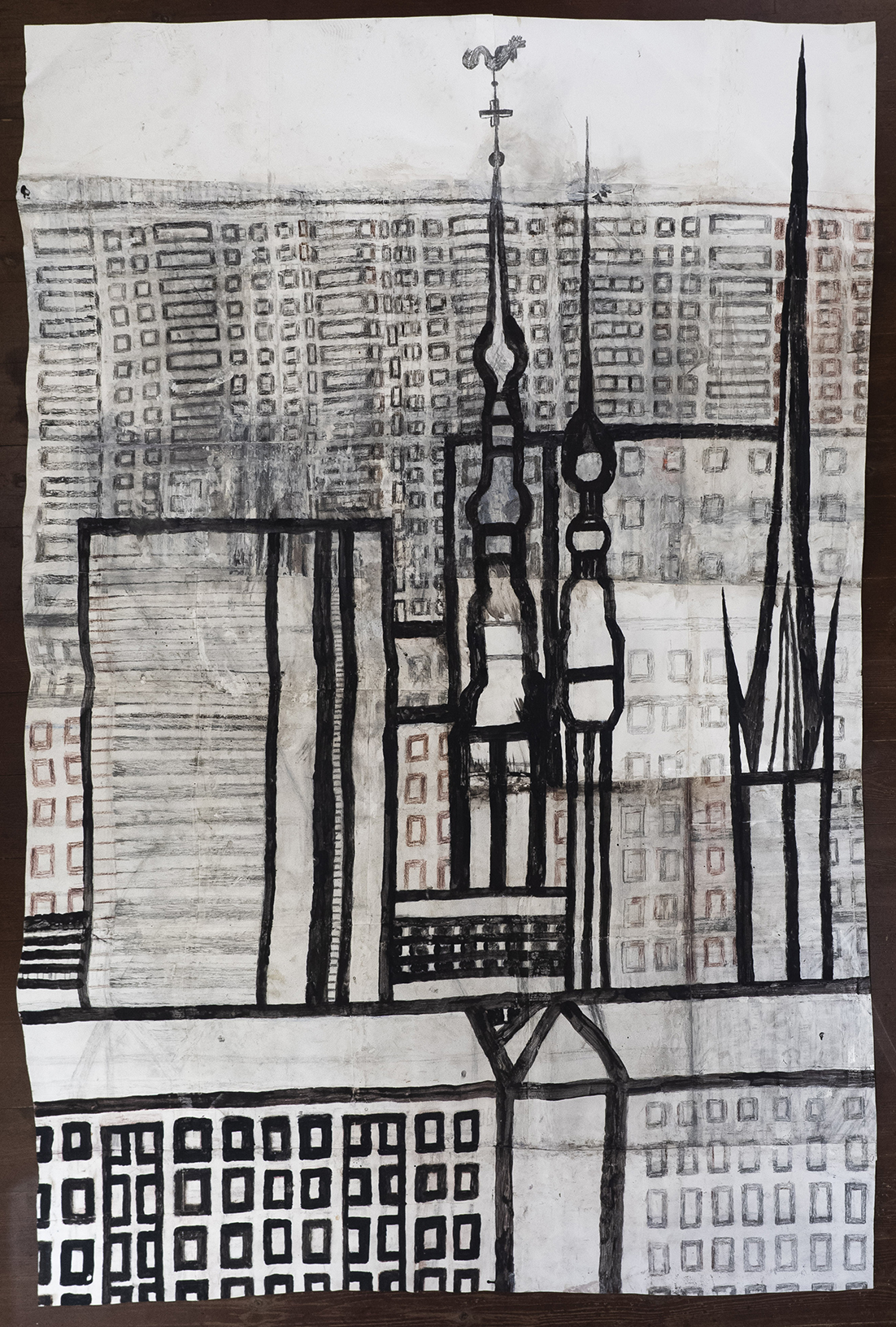

Jüri (b. 1971) lives in the largest special care home in south Estonia, in the city of Võru, where he was relocated as an adult after his mother died. He graduated from the Urvaste special-needs school but after coming to the care home, he stopped communicating. It took a long time before he began drawing with others in the activities room. Increasingly, his semi-abstract works began including dates and a few words. When he was asked something, he wrote the reply on paper; sometimes he would secretly hide scissors in his pocket and would cut up his shoes, unscrew skirting boards, or even his entire bed. When Jüri saw his works in the Kondas centre in 2018, he suddenly became extremely social, began speaking and once, disappeared in the city of Võru for two days. After this incident, his treatment was altered. In recent years, he does not draw as often and most of his works are black and white.

Based on these two brief examples, we can see that creating art is a tool for people who need additional support to better perceive and analyse the world around them, but it also provides others with the opportunity to understand their inner world.

Making talented creators visible and recognising their work helps people who need additional support to gain better conditions for making art and help society understand that different people should be met on equal grounds, which, in turn, helps create more cohesion in society in general.