”Nature” was invented to separate wholes from their parts, things from each other, and us from the rest of the world.

Regardless of pace, landscapes are always sites of transformation and mutation, where a variety of imaginaries exists simultaneously – places where ecological, political and social concerns entwine with mythological, folkloric and magical thinking.

What follows here is a tentative look at landscapes and their echoes in material-focused artworks. But rather than rendering landscapes in pictures, in the tradition of landscape painting or drawing, or trying to capture landscapes in their totality, in material-based practices, only parts of the landscapes are materialised. Nevertheless, the landscapes and worlds these objects suggest, from which they sprout are equally rewarding to imagine, allowing us to question our own understanding of the relationship between the whole and its parts.

Regeneration of what?

As the human eye glances at stone, it is designated a resource and the process of its industrialisation begins. And so, Laura Põld’s series of lumpy grey clay sculptures fitted with water, smoke and light, too, evoke an industrial landscape. Titled Wasteland (The Phosphorite War), it is not an image of factories and production but rather an exhausted and abandoned terrain. The title of the work references a very specific moment in time – an extensive environmental campaign in the 1980s against opening large scale phosphorite mines in the eastern part of Estonia, which at the time was part of the Soviet Union. In addition to standing successfully against Soviet industrialisation, the campaign notably strengthened the national movement, which later led to restoring of the country’s independence. The work also resonates with the current energy crisis and the related questions of energy autonomy and security. Even though the landscape once withstood the threat of colonial extractive industrialisation, is the mining of resources that led to increased environmental damage justified now, when it is no longer done by colonial powers? It is, of course, always a question of ownership of resources and the scale of extraction – will it lead to devastation or leave room for regeneration?

Although Põld’s work materialises industrialised wastelands, landscapes that are transformed by humans, she does not only address the possible environmental cost of industrial extraction but also considers the possible agency of the mineral matter. Through her amorphous objects and somewhat more dynamic elements of smoke and water, she consciously looks at the weirdness of minerals, resisting the singular view of resourcification. Her perspective on the natural world is not scientific and concerned with presenting a factual image but rather different sensibilities present and the possibilities of what else, besides resources, can be (re)generated in the landscape and what else comes alive there, what kind of fruit can it bear.

Return is not advisable

In these landscapes, even the most familiar of fruits can bewilder us – at first glance seemingly rotting, the apples are actually leather. In an uncanny mutation, plant and animal have merged, making it a troubling effort to imagine an ecosystem capable of producing such apples.

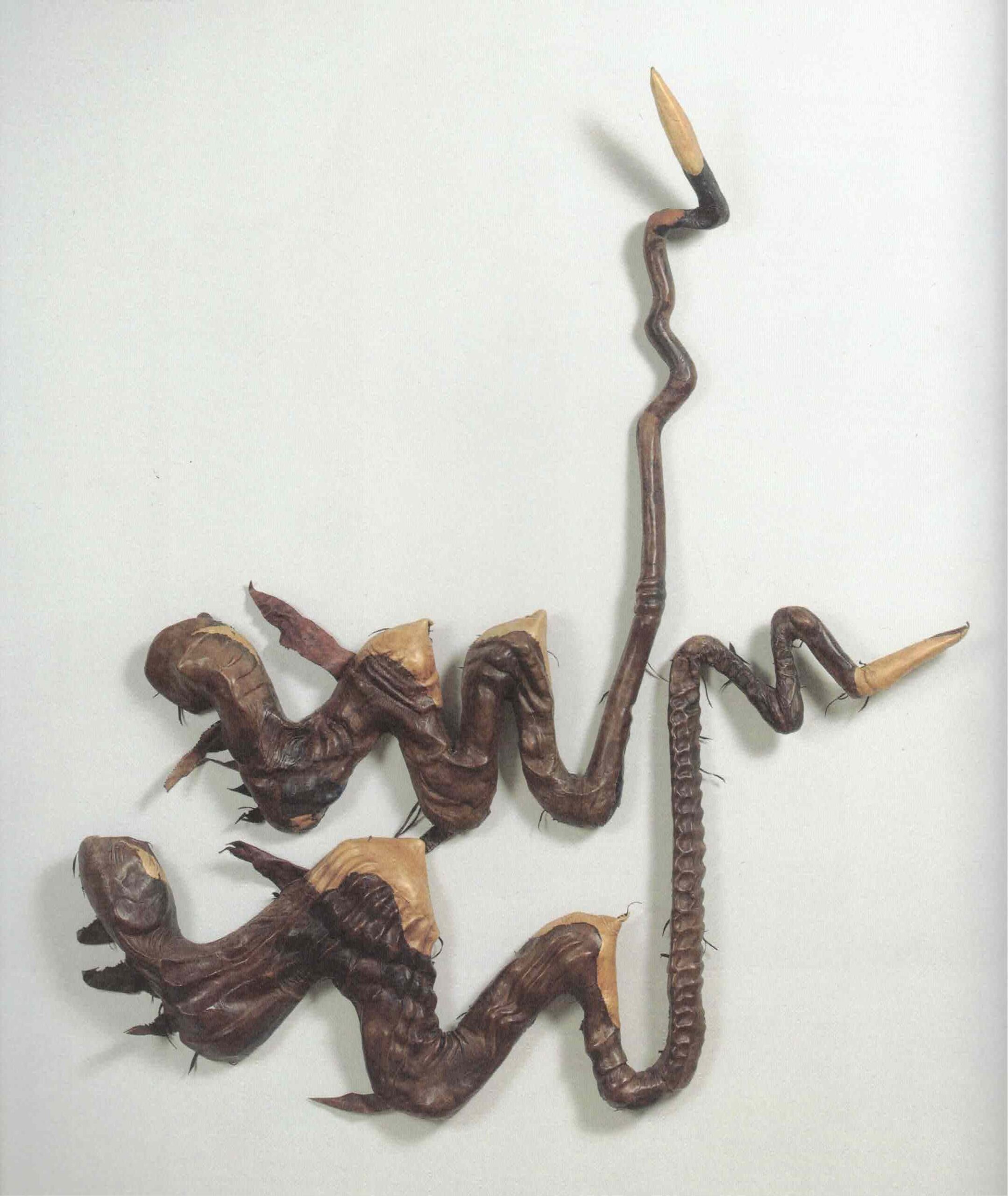

The pair of leather apples is created by the artist Elo Järv (1939–2018). She is primarily known for her leather sculptures and even though her work is most often categorised as applied art, her practice stands out among her peers in terms of the unconventional use of materials. Järv’s work presents an abundance of nature motifs but often hints at mythology and the unseen forces shaping our understanding of the natural world. The materiality of leather in her sculptures brings a visceral and sometimes eerie dimension to objects, making them perhaps a little difficult to place and suggesting strange and wondrous (natural) worlds, as we see in My Insectivorous Totem (1995) and Insect (1996), for example. It is difficult to say, whether the mutated forms hail from a place of disquiet or calm, but at times caution should be exercised, as suggested by the pair of spindly formations Return Is Not Advisable I, II (1994).

It is not only non-humans that exist in these spaces, anthropomorphic forms with their leathery bodies and faces often appear among Järv’s creatures as well. It is not exactly clear if these humanoids are autonomous beings, their shells, shrouds or other representations of memory. Regardless, looking at Järv’s sculptures, I recall The Bog Man – a short story by Margaret Atwood, in which the protagonist Julie has an affair with an archaeologist excavating a bog body and recalling the man years later, she finds herself conflating her former lover and the dead man in her mind: ”Connor, however, loses in substance every time she forms him in words. He becomes flatter and more leathery, more life goes out of him, he becomes more dead. By this time, he is almost an anecdote, and Julie is almost old.”

Indeed, the passing of time is an important aspect to consider when looking at Järv’s sculptures. As time passes and human is no longer a measure of everything, it becomes more of a body than a person. This is emphasised by the instability of organic matter that sits at the forefront of her works. Unlike bronze or stone sculptures, the fragility of the material is almost palpable. This is something Järv is also very much aware of. The work Old Leather Returns (1999) contains an obvious reference to the material and the possibility of re-use and recontextualisation, but is also perhaps suggesting something more sinister – a return from or to a place where return is not advisable.

It sprawls

The increasing industrial devastation of landscapes also sets limits to what we imagine possible in and for the landscape, making people aware of the very real danger of soon having nothing to return to.

The performance and textile-based work of the collective Sorcerer evokes the industrial landscapes populated and polluted by massive textile waste. Their imagination relies heavily on poetics but is also not detached from the real landscapes from which dispossessed creatures, neither human or animal, arise. Using recycled materials, they look at industrialisation and its spawns, while also presenting a more magical view of the world.

In their latest installation Lustwort, created as part of Heinrich Sepp’s work Made of What (2022), they contemplate the queer materiality of the bog, a type of landscape that does not easily submit to rule and industrialisation, despite having historically been subject to it. Writing on swamp modernity, Egle Rindzevičiūtė says: ”The swamp is antithetical to the linear, mechanistic mind. It defies communication enabled by clear waterways, resists agriculture, and questions human mastery of both territory and living matter. In cultural terms, the swamp stands for tradition, something that is the enemy of progress in the framework of modernization theory.”

As the climate, and landscapes with it, increasingly slip out of human control, perhaps a similar process of non-compliance becomes the norm as we blend into the composite landscapes of material of varying origin, both human and not, and become one with our waste. There is always something monstrous in entities that remain ungovernable and unreproductive – uncertain landscapes populated by monsters, or perhaps, these landscapes are the monsters.