Pia Arke (1958–2007) was a Kalaaleq

Hanna Laura Kaljo:

Born to an Inuit seamstress and a Danish father, Pia Arke emigrated to Denmark at the age of 13 and never learned to speak Tunumiisut (East Greenlandic), her mother’s first language. She returned to Greenland as an adult to photograph her childhood landscapes, which referred to her origin but with which she lacked a living relationship.

Her work speaks of the condition of displacement, of being torn out of context, and the loss it evokes. At times, this is a loss of a land-based identity, which would hold a sense of continuity between one’s past, present and future. When one moves, or is removed, memory remains the territory of one’s belonging. But how does one remember when what has been passed on is silence?

As a representative of a generation born into the echo of displacement, Arke directed her fractured gaze, often with the help of the camera, towards the repression of her foremothers. She allowed the silence, which lingers over the shared colonial history of Greenland and Denmark,

Ann Mirjam Vaikla:

I remember encountering Pia Arke’s work first in 2019 at the 16th Istanbul Biennial (The Seventh Continent, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud). Five large-scale collages Legend I-V (1999), were made of geological maps of Arke’s birthplace Ittoqqortoormiit (Scoresbysund) in Greenland, family photographs including images of Arke’s mother, and traces of colonial goods such as flour, coffee, sugar, oats and rice. Masterly compositions intertwining the scientific and personal narratives underline Arke’s artistic principle: “I make the history of colonialism part of my own history in the only way I know, namely by taking it personally.”

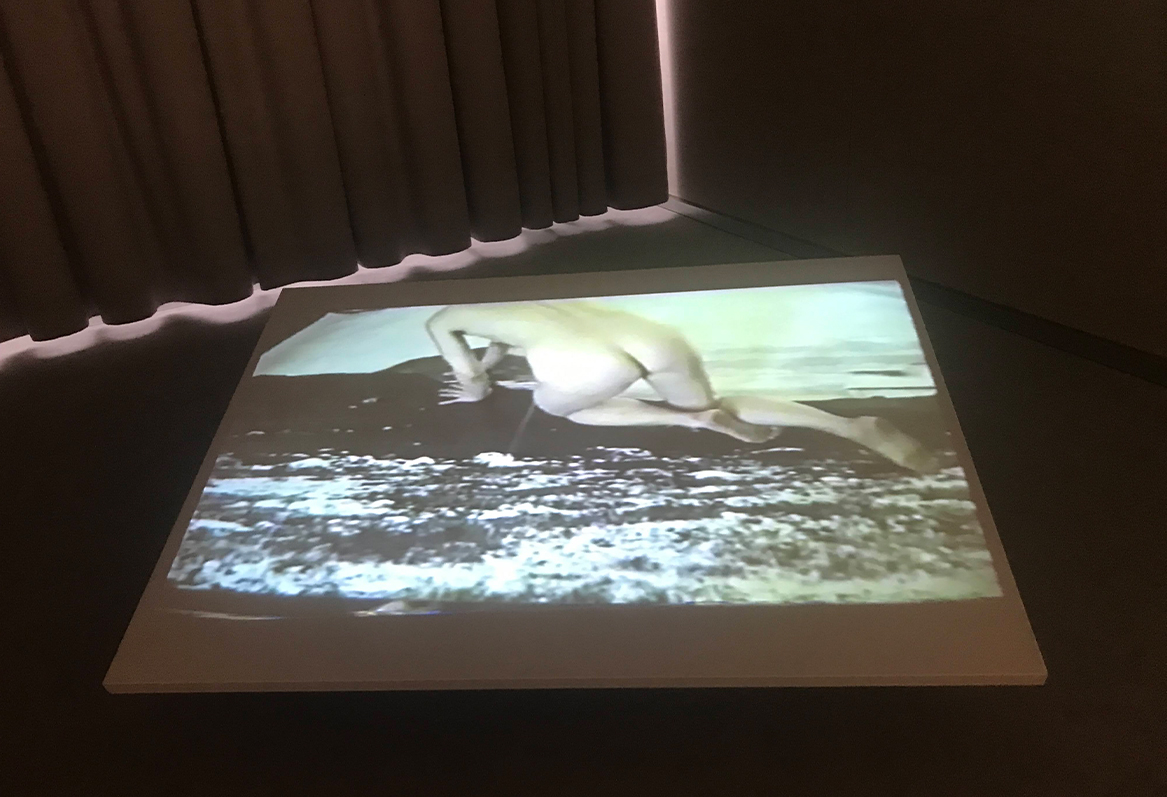

Soon after, this first encounter with Pia Arke’s oeuvre paved the way to exhibit her work in Estonia. The video Arctic Hysteria (1996), loaned from the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, became part of a group exhibition “Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention” (2021) at NART–Narva Art Residency. In the video, Arke crawls naked over an image depicting her childhood landscape, until finally ripping it apart. This feminist gesture draws the viewer's attention to how Western explorers pathologised Inuit women, and ignored their resistance to being photographed and classified by the colonising power.

Part of an exhibition concerned with environmental change, Pia Arke allowed co-curator Saskia Lillepuu and I to address the local context of Ida-Viru County, located in eastern Estonia, through a colonial lens. Ida-Viru County contains large deposits of oil shale, used for the production of shale oil to generate electricity. Industrialisation of the region and mass migration during the Soviet era resulted in Russians largely replacing the indigenous Estonian population. Nowadays, declining industry has caused the highest rate of unemployment in the country. So, Tanel Rander, one of the invited writers for the exhibition catalogue, refers to it as a sacrificial area: “Social welfare states maintain sacrificial areas that are generally far away, in a former colony or in some periphery. A hole has to be created for a castle to rise. Estonia’s main sacrifice area is Ida-Viru County.”

HLK:

In early 2024, our attention was drawn to Arke’s piece Self-Portrait (1992): a black and white photograph depicting the landscape of southern Greenland, near the town of Narsaq, onto which the artist had placed her naked body, her back to the viewer. This image became a guide through the exhibition Ann Mirjam and I wanted to make. I saw in it a body caught between two currents, two worldviews – an Inuk lineage and a Danish lineage – and an artist working to bridge the silence that lingers in the aftermath of displacement.

Arke shows us that memory does not reside in the mind alone. As the social anthropologist Timothy Ingold writes: “to follow a path is to remember the way.”

AMV:

We ended up choosing Arke’s photographic series Nature Morte alias Perlustrations I–X (1994). Ten silver gelatine photographs depict haunting still lives: the artist’s hand at the beginning and end of the series, a toy dog, leather-bound science books, a portrait with closed eyes – but most strikingly Arke’s friend’s scarred body from a mastectomy. Curator Anders Kold writes: “With cartographic sobriety, Arke records the scar from the removal of her childhood friend Susanne Mortensen’s left breast. The likeness to the modified map, to which sugar adds a relief-like effect, is uncanny”,

In the context of They Began to Talk, this work emphasizes the indigenous knowledge of the inseparability of the body and the land. Violence, committed on land due to colonial and economic gain, also leaves the inhabitants of the place wounded. These invisible wounds are passed down through generations, resulting in a centuries long process of environmental trauma.

In dialogue with artists from Estonia, the Baltics, and indigenous artists from Sápmi, Pia Arke is a guide to a deeper understanding of the condition of displacement. In an era of neocolonialism and rapid environmental change, she helps us to imagine the possibility of recovering a sense of connection where it has been severed. Arke does so by showing the way to a wider understanding of who has the ability and the right to speak, and that art making, as an embodied activity, can be one of re-membering.

They Began to Talk is open at Kumu Art Museum from 7 February to 3 August 2025.