More than a century ago, modernist artists visualised the emerging body politic, where the social was fashioned into novel shapes in concrete, steel and glass and motored into the future by land, sea and air vehicles. Yet the fit of infrastructure and the social was uneasy: throughout the twentieth century, the social body grew in bursts, spilling over in its exuberance, bulging where it was not meant to, elsewhere shrinking, leaving the shell empty. The old infrastructure could not keep up with the accelerating metabolism: being stiff and eventually rusty, it scarred the social, grew into its crevices and made it stumble, restricting its movement with a tight corset of the past dreams. What was meant to be a backbone became a bother. What used to be shiny armour began to resemble an ingrown nail.

In the 2000s, European integration spurred infrastructure growth, expecting to bind East and West societies more closely. Infrastructures, like pieces of titanium used in surgery, were to join the bones of entrepreneurship, to weld the landscapes of creativity, forging new transnational selves that know no boundaries, but why do these late modern selves keep disaggregating in our gaze? The blurring effect is part of perceiving what Timothy Morton described as hyperobjects.

We focus and refocus on the blurred infrastructures responding to unexpected events. The last few months have made it clear just how much vulnerability has been confined to the blurred-zone by the progress-oriented narratives of technological futures. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 exploited the vulnerability of the power networks using transport infrastructure to move military units, targeting energy generators and dams with missiles. Even nuclear facilities were not spared. Everything considered impossible in the world of safety norms and international agreements became possible with the shelling of the Kharkiv nuclear research reactor and the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, with the ruptured NordStream II, spitting gas into the Baltic Sea, resembling Anish Kapoor’s inverted fountain (Descension, 2014). Like a whirlpool, the future itself sometimes appears to be sucked into the hypothetical present, for instance, where the RAND war game on Russia (2014–2015) invading the Baltic states showed that occupation would be fast – the speed of invasion facilitated not only by the small territories, but also by the excellent road network, the result of three decades of intensive development since 1990. Maybe road and rail are not belts but whirlpools.

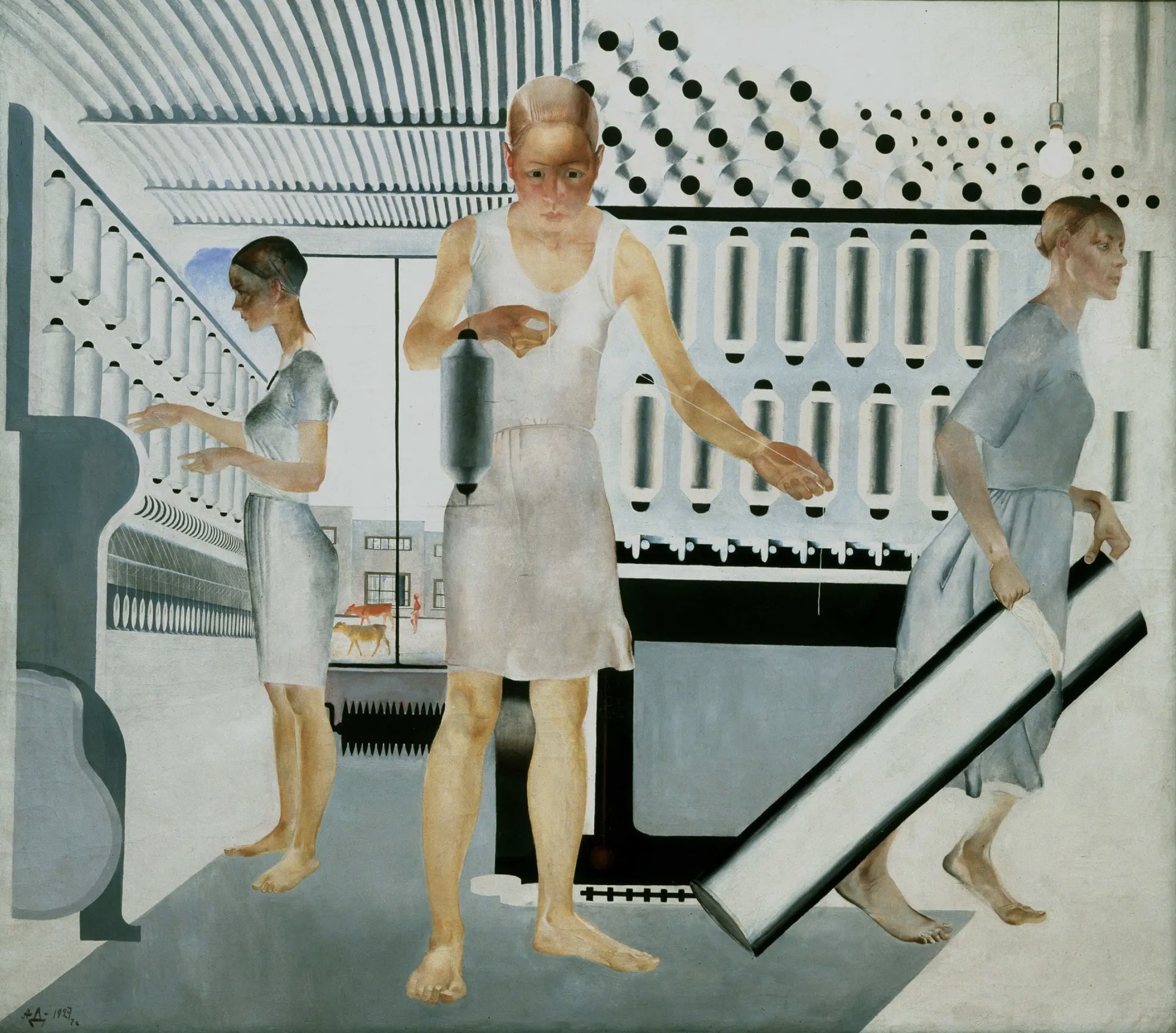

However, the ingrown infrastructures emerge from the blur as they enter the cultural imaginaries of industrial landscapes, which are ambivalent in the Baltic states. The socialist realist canon glorified the infrastructure’s finite nature, rational form, and highly synchronised flow resulting in a perfect cosmos of machines, production lines and humans (Alexander Deineka, Textile Workers, 1927). This crystal-clear official vision was disturbed by the blur both literally and metaphorically, where painters merged expressionist and cubist forms to disturb the clear shapes and complete visions by presenting humans as fragmented, entropic figures in the dysfunctional contexts of cities, factories and machinery (Vincas Kisarauskas, Figures Without a Future, 1976).

The Ukrainian last stand in Azovstal, the industrial steelwork city within the city of Mariupol, is the ultimate expression of the grandeur, drama and tragedy of the post-Soviet industrial lifeworld. Unlike in Ukraine, where both national and industrial narratives are cast in an ultimate heroic form commanding global attention, the cultural imaginaries of the Baltic industrial infrastructure, its failures and securitisation consist of rather small stories, being, thankfully, unmarked by large, distinct catastrophes. The echoes of the big and global stories, the big drama, are carried by isotopes in the bodies of the Baltic workforce sent to Chornobyl: over 17,000 Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian men were sent to clean up Chornobyl between 1986 and 1991. This generation is ageing; their memory is at risk of loss. The more visible remnants are the toxic architectures of the piles of oil shale in Estonia and the mountains of phosphogypsum in Lithuania. The turbulent refurbishment and expansion of Soviet cities generated quiet landfills of industrial waste – plastic window frames, concrete and asbestos. Anna Storm called such places ”landscape scars,” where society and nature come together to resolve and heal the ruptures caused by twentieth-century industrialisation.

The Baltic industrial dramas are more like a TV series with many episodes than feature films: the misfortunes and tragedies could appear rather small, but they add up and form a chain of infrastructural injustices that need to be reconstructed to be recognised for what they are. In Lithuania, the best living memorial to the suffering of the industrialised countryside is the cow – or a horse – chained to a spot in the field, a witness of property relations that were destabilised in the communist period, where farmers were not bothered to plant hedges or build fences to enable animals to graze freely.

Post-Soviet art turned to the fragile, post-utilitarian image of infrastructure witnessing failed Soviet modernisation. The crumbling concrete from the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant communicates its archaeological, fossilised value (Augustas Serapinas, Vygintas, Kirilas and Semionovas, 2018). Others, like Emilija Škarnulytė, find order in disorder, rejecting the entropic effect of the blurred vision by filming industrial infrastructures in such a way that they appear as seductive, living, organic environments (Emilija Škarnulytė, Burial, 2022). In the industrial landscapes, nature becomes ”the negative form” of industrial infrastructure, reclaiming its punctuated, incoherent and painfully mundane spatiality through vegetation, fog, snow and rain (Jonathan Lovekin’s series, Infra-, 2015–2017). A hyper-macro lens on the industrial infrastructure rehabilitates it as an object of the modernist aesthetic: in Agnė Gintalaitė’s photographs the weathered doors of Soviet garages grow layers of patina becoming canvases of expressionist painting, but the painter is the hostile Baltic weather (Agnė Gintalaitė, Beauty Remains, 2015).

Not only the communist regime but also that of neoliberal capitalism has scarred the Baltic countryside. In the last decades, the most visible form of everyday geo-extractionism in the region is sand and gravel quarries. Entrepreneurs buy plots of land – usually abandoned agricultural fields – to extract materials for the booming construction business. To observe a quarry being born is something to behold. First, the topsoil is ploughed to break up the roots of tall, established grasses, which hitherto had hosted migrating crane, as well as hare and roe deer. The topsoil is peeled off and sold to garden centres, so that city residents can pot their house plants. Then, gravel is dug and transported by diesel-thirsty lorries, roaring their engines through the woods and fields, now scarred with purpose-built roads. Once the gravel is exhausted, the military may move in to train battle action in those complex terrains. The entrepreneur will remediate the site by returning it to its natural condition. The topsoil, however, is gone forever, relegated to the blur, whereas those new pavements in town centres, roads and bridges are in sharp focus as symbols of growth – or, shall we say, the new forms of ingrowth?