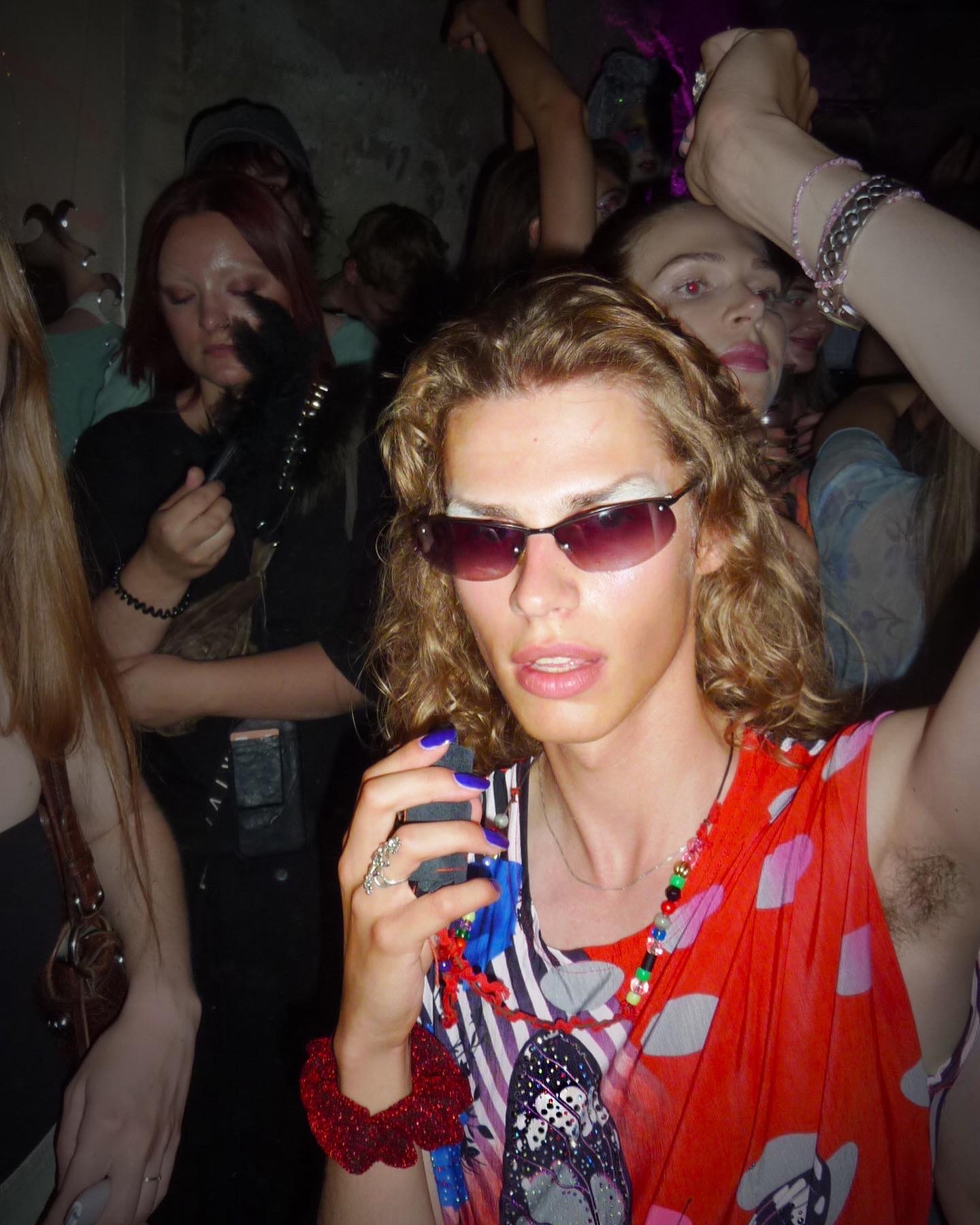

Earlier this year I came across McKenzie Wark’s book Raving (2023) in Rile bookshop in Brussels and bought it on a whim. It soon became my favourite book of the year, and since then, I've tried to get a hold of her other books as well.

In a slight moment of insanity, I sent her a dm on Instagram, asking whether she'd be willing to take a look at a research article I was writing on raving and music. At the same time, I also felt I would be missing an opportunity if I didn't also ask her for an interview. So, at the end of September, I talked to the Australian-born New York-based writer, professor of Culture and Media and director of the Gender Studies programme at the Eugene Lang College at The New School about music, religion, a little bit about Marxism, queer and trans literature, and how gender affects language and writing – all of which are my favourite topics. I certainly came away from this conversation with new perspectives, and I hope you will too. We started with raving.

Gregor Kulla: Did you go to a rave yesterday?

McKenzie Wark: Not yesterday, no. We launched my new book Love and Money, Sex and Death, and after book events I just want to go home. I usually don't go out afterwards. The last time I went dancing was last weekend. On Sunday, it was a day thing.

GK: Do you usually go to raves during the day?

MW: Well, in the morning, actually. From around four or five until nine or ten. Something like that. I skip the rush hour and wait until all the drunks have gone home.

GK: I’ve noticed that raving is often likened to religious experiences. In one of your previous interviews, you mentioned that you're not religious yourself, but you have faith in things outside religion. Like books, your work, nirvana...

MW: I remember a passage from the book Bird Lives!, where Charlie Parker was asked about his religion. He said “I am a devout musician.” I'm a devout writer and a third-generation atheist, so I never had much access to a spiritual language.

But the rave scene in Brooklyn does have something cult-like to it. Raving is not just another way to spend time but a need. It evokes a sort of state of mind we feel is necessary for us. And sure, this may be similar to experiences people have when participating in ecstatic religions, the kinds that offer a collective catharsis. Then again, what gives techno this evocative quality is the fact that it's rooted in Black culture that has been altered and appropriated over many years or even centuries. I believe it is important to understand this. But personally, I don't see the need to discuss raving through a religious language since I don't have a religion myself.

GK: In your books, you have covered a variety of themes, including capitalism, hacking, gender, social issues, sexuality, as well as raving, among other things. What would your ideal world look like? Who would be part of it, and how would it function?

MW: For me, these themes are all the same thing. But the world we live in now is temporary. It won't last. And we don't know what kinds of practices could endure. We have no cultural memory of massive geological changes. In Australia, there are indigenous peoples whose cultural memory dates back before the Holocene, but this is rare. Our understanding of culture is rooted in the current geological era – we are living in, and it is also coming to an end. This is amazing and scary at the same time. Nobody knows what will remain and what will not.

K: Your transition is also one of the topics in your writing. Do you feel that your gender transition affected your writing or the way your writing is received? Is this a change you need to actively address?

W: I feel people have started taking me less seriously. And that's amazing. All the serious Marxist theory bros no longer pay attention to me. Some of them still think I have some sort of mental illness. So I can do whatever I want, which has been liberating because nobody takes women seriously, much less trans women.

But I've found new readers, fascinating people, who are much more open to investigating the modern human. And I also started writing with and for other queer and trans people much more explicitly. And that's fun, the fact that I've had my little pocket of readership. However, I do hope that my new book Love and Money, Sex and Death, will also reach readers outside the queer and trans community, as it quite literally discusses love, money, sex and death. We are all trapped by these four things, and a transgender view offers a different perspective on these issues. Hence, it would be great if it found a broader readership. To the mainstream, trans people are often like tourist attractions, and we are not taken too seriously.

K: Has it been difficult for you to expand your circle of readers?

W: I can find my readers pretty well. I put a lot of work into this over the years and the readers I lost when I transitioned I probably wouldn't care for anyway. I have found a new readership and sometimes mixing the different audiences is fun. When I was touring in Colombia with Reverse Cowgirl that had been translated into Spanish as Vaquera Ineritia, when I discussed the porn section of the book, I also got questions on the nature of capitalism. I love mixing these themes because everything is connected. That's why it's so fun to be a writer – I can write and have knowledge about different things without needing the status of an expert. When I write about something, I do in-depth research, and I hope I will be able to say something new. And essentially, that's what it means to be a writer.

K: I would also like to approach you with a sensitive question. As you perhaps know, in the 20th century, Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union for a long time, and we can still find traces of the Soviet mentality present in our society. When travelling or even when reading French literature, for example, I've noticed that Marxism is romanticised in the West. This makes me feel funny, and as for the majority of Estonians, it's still a very sensitive subject. In your latest book, you wrote about your relationship to Marxism, that it was and still is part of your life. I feel like talking about Marxism is not a thing here in Estonia, compared to the States, for example. Or maybe I haven't had the opportunity to take part in these discussions, so I'm not always sure how to approach Marxism or other topics that are tied to it. Is it even allowed? In the Eastern part of Europe, it is often said that people who have not lived under Soviet rule have no right to discuss it, and in the West, that people who have just don't know what true Marxism is. How should we think about this polarisation? What is your approach to this issue?

W: I mean, Stalin murdered all the Marxists, and by around the mid-twentieth century, there weren't any Marxists left in the Soviet Union or its captive states. The Marxists lost, and it became a Russian autocratic state again. Yet another failed experiment in multi-ethnic Russian imperial autocracy. Marxists are not to blame for the Soviet Union. So, I think that the first issue is the Soviet Union's claim to legitimacy. The October Revolution is just one I've never accepted, and many Marxists didn’t at the time. We lost. There's more continuity in the autocratic forms of the Russian imperial state than breaks in it. And autocracies do tend to have rather violent and unpleasant ways of renewing themselves.

When we talk about Marxism, we often do not talk about the same thing. Probably the generation of your grandparents was taught "Marxism" in school, I've read these books and they are complete nonsense. So now there's a paradox where people who were forced to read something that described Marxism feel that they know what Marxism is although that's not the case. They read the Soviet state ideology that the books called Marxism, which now looks stupid. Marxism is a living tradition, a struggle against power. And if we do not touch on this strange paradox, we will continue talking about different things.

I went through this in the 1990s, when we tried to organise online both in the East and the West. The struggle with language was very real for that same reason. When you try to put people from Poland and Italy into the same room, but they have completely different linguistic and historical experiences with the language of “Marxism,” and even though both are in support of a free and democratic society and share common interests, like techno, for example, it was language that posed the greatest challenge, as we were using the internet and other digital tools. The language, of course, was English, everyone's second or third language, so good luck trying to use an international language like that to discuss these themes. It has always been complicated.

I went through this in the 1990s, when we tried to organise online both in the East and the West. The struggle with language was very real for that same reason. When you try to put people from Poland and Italy into the same room, but they have completely different linguistic and historical experiences with the language of “Marxism”.

K: Language is indeed a fascinating tool and not linear at all. You have mentioned that you write in the autofiction genre, which, similar to the paradox of Marxism, combines two mutually inconsistent narrative forms, namely autobiography and fiction. I, too, consider my writing autofiction, and I have noticed that many other queer and trans writers do the same. Why do you think that is?

W: To answer this question, it seems easier to start from the other end. When we think of the history of the novel, who have been the minor characters? That would be us – we have been on the margins of the tradition, if not left out completely. Now, we may ask – in what form could queer and trans people have a literature at all? We can give it whatever name, but something needs to change so that we can give space to other kinds of experiences. Let's call it “autofiction” out of convenience. Jean Genet was among the writers who kind of established the genre. His book Our Lady of the Flowers focuses on trans themes and it's autofiction. It may or may not be Genet's own story, and it doesn't matter much whether it's Genet or his fantasy, as it is framed as a masturbation fantasy set in prison. It's told through a self that makes no claim, no truth claim and does not claim that knowledge of the self is a path to truth. That is how it differs from a memoir or biography. As I said before, my interest lies in trans literature, which has often had to find ways to bend and reform experiences that are illegible.

My new book Love and Money, Sex and Death is like a correspondence. And it turns out many trans writers use the letter format in their work. My guess as to why the text is written to a particular person, real or imagined, is that it frames how you want the writing to be received by the reader of the book, who's like the third point of view. So, you know, if you know that you're a minoritised population, you don't have a lot of agency over how you're perceived or how people read you. But you can model how you want to be read by putting a reader into the text who is actually reading along if you like. So, this is how interesting stuff around form has tended to come out of minor literatures on the edges of the grand centralised tradition of the bourgeois novel, which is always about marriage and property at the end of the day, and the novel of national destiny. Every culture has one or several books of this kind and there is always someone who's been left out. I think what is truly interesting is always sort of in-between and marginal. The best English writer, Samuel Beckett, wrote in French. He emigrated to France from Ireland and only as an outsider became part of the English literary canon. And this keeps happening again and again. Beckett is an example in my language. I don't speak Estonian, so I can't give any examples there but surely there are some. Everything exciting always comes from the outside, right?

If you're a minoritised population, you don't have a lot of agency over how you're perceived or how people read you. But you can model how you want to be read by putting a reader into the text who is actually reading along if you like.

K: Right, right. I totally agree. But how do you feel your experience of writing has changed after your transition? Do you consider your texts masculine or feminine, top or bottom?

W: It is often said there's an accusation of trans women that we're male socialised and there's an element of truth in that. I was trained to have confidence and to believe I could do things and thought I had a right to assert things. The world is full of straight white men who have nothing but confidence. They are everywhere, yet the social glue that holds everything together is femininity. But the way masculinity and femininity are distributed doesn't neatly map onto bodies.

The way masculinity and femininity are distributed doesn't neatly map onto bodies.

Some cis-women perform masculinity to gain power and achieve success. And there are men who were born men but are not at all interested in having or achieving. Some of us transition and some do not. There are forms of femininity that some men practice. But what if I just sit back and listen and try to figure out how everybody feels about a situation instead of just blundering through it? It's good to mix different qualities because on the one hand it can also happen that you end up vibe-checking a bit too much, and then again, decisiveness is not necessarily a bad thing.

What would be helpful is the balancing and skilful application of these characteristics because often masculine traits are not very useful in complex interpersonal, technical and social situations and projects. They just don't do well. The level of mid-management is dependent on femininity to a great extent but then, at the upper levels, we often find a ridiculously confident man, beyond accountability. Masculinity truly is in crisis today. What are its positive traits and how to use them? Male-presenting people have had free reign to get what they want to such a large degree that this is a very difficult question to ask.

If we lived in a world that would not automatically prioritise masculine language, capabilities and skills, we could think about the role of masculine traits in today's society. Gender as such is fine. I don't think we should abolish it completely. Gender is a language, and it could be fun to play with if there wasn't so much power and coercion attached to it. And it's also closely linked to sexuality.

Gender has been shaped by the development of media culture. During the broadcast era, men, women and young people watched the same series on TV in prime time, listened to the same music or read the same newspaper. There had to be a sort of negotiation about genders even though there was still a hierarchy between them. So, there was a conversation going on, but in the post-broadcast era, everyone has their own media. Men have their own media sphere, which is exclusively consumed by men and of no interest at all to most women and femmes. In this way, gender has become a media project and there is no dialogue within or between these media, they have become ridiculously self-referential.

I hear about this so much from women I know who date men. They're going on dating apps and can't have a conversation. They’re like, “I met an incredibly hot man, but his entire life revolves around video games and outside that there's nothing you can talk about with him. Like I can't invite him to the cinema or anything.” These cultures of gender have become separated from one another to the degree that it has become difficult for people to even talk to one another. We are in the midst of a male loneliness epidemic. Suppose a person has not figured out how to communicate with another person or open up and can only talk about fishing or football. There's a crisis of figuring out what a different kind of masculinity would look like.

I have that perspective because I did cosplay masculinity for quite a long time. I never believed in it, nor did I want it. And I finally gave up.

K: But how do you feel your texts changed after you transitioned?

W: They changed a lot. Hormones have a huge impact on the body – they change how it functions and how you feel about it. You write through the body; the body is your instrument. So, when you transition, you also change your instrument. It's like if I were a musician and my instrument had always been the clarinet but now it's the saxophone. These are similar instruments – when you know how to play the clarinet, you know a little about how to play the saxophone because the fingering is not so different. But you don't know how to play the saxophone well because it doesn’t function exactly the same. I had to learn to write again in my fifties, which was really difficult. Nothing worked for three–four years, and that was an extremely long time for me as an active writer. Raving was my comeback. Raving was a commission, and the external pressure and looming deadline were helpful. I pushed through, and I feel my texts are now somehow richer. My earlier books avoided the bourgeois middle voice by being more abstract. After my transition, I decided to write in an overly intimate voice. Let's just make it too intimate and miss that middle sort of stretch of polite bourgeois civility. Let's get real! My latest books have that kind of quality.

Let's just make it too intimate and miss that middle sort of stretch of polite bourgeois civility. Let's get real!

K: And to finish off – in your book, you mentioned an incident that really made me cackle. You wrote how sometimes on the street, people ask you in a threatening way whether you are a man or a woman, and because of your feet, you can't run, so you just say "yes." Have you become immune to situations like these?

W: It is tiring. But to act confident is a necessary skill. In situations like these, for instance if I get side-eyed by a random man who thinks he has the right to judge the way I look. I look back at home, and I see a man in a way-too-tight t-shirt who looks like his mother picks his outfits. And he’s 40 years old. And he judges how I look? Fuck off!